On 30th March 1856, the Crimean War was formally brought to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

This formal recognition signed at the Congress of Paris came after Russia accepted a humiliating defeat against the alliance of Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia. The treaty itself would address Russian expansionism, quashing dreams of a Russian empire equal to none, whilst at the same time confirming the importance of the Ottoman Empire in maintaining a very tentative balance of power in Europe.

The Crimean War which had begun in October 1853 lasted eighteen months and in that time had escalated into a series of fragmented battles and sieges, causing huge loss of life and highlighting wider issues and failures pertaining to leadership, military intervention, mortality rates, medicine and mismanagement.

The war itself garnered a great deal of attention and proved to be a significant and defining moment for Europe. It was first and foremost the embodiment of a ‘modern war’, using new technologies that would later characterise the wars of the next century.

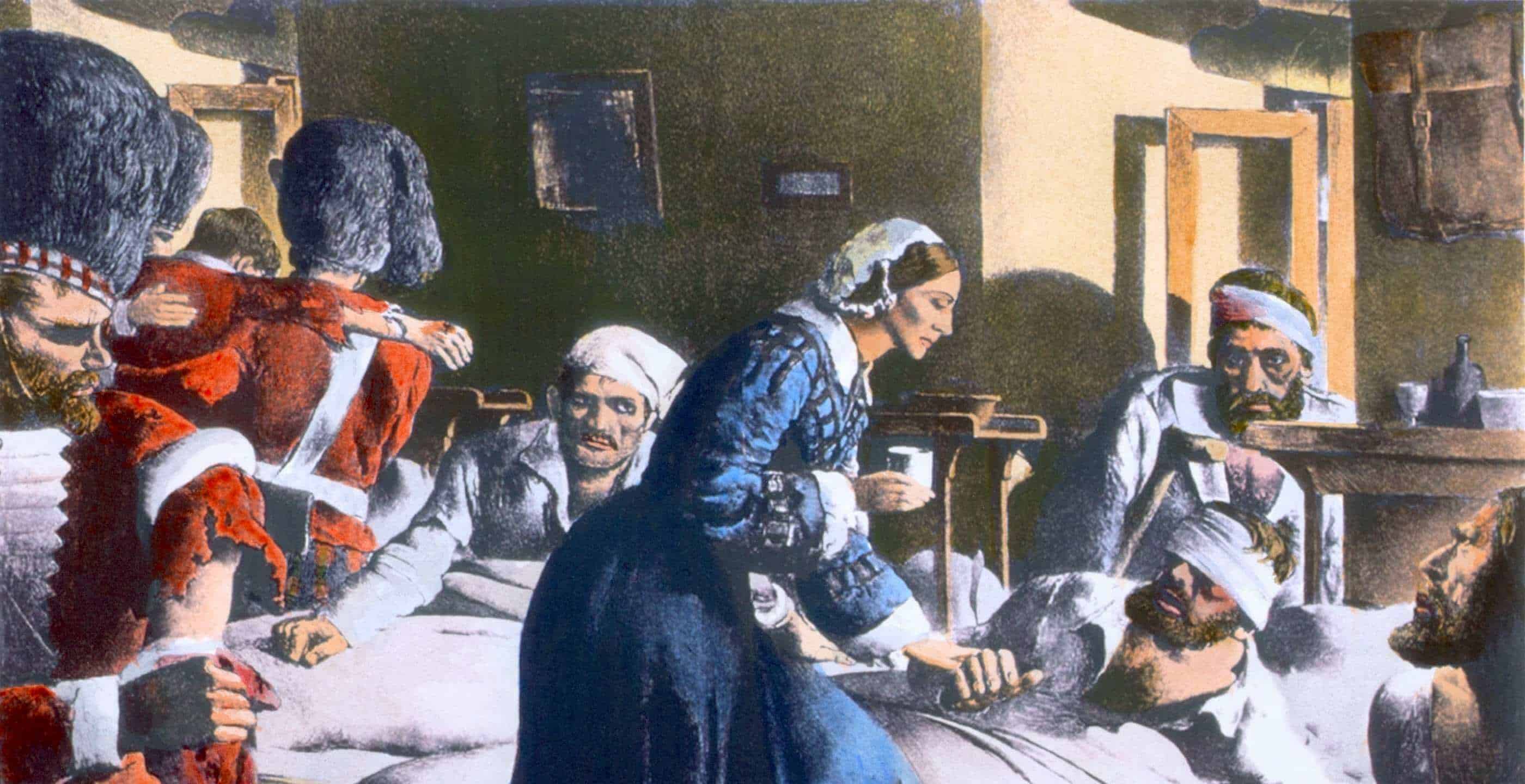

Furthermore, the coverage of the war in newspapers, particularly in Britain allowed the general public to experience the horrors of war in a new and provocative way, thanks to reporting by the likes of William Howard Russell for The Times newspaper. This overseas reporting combined with information from significant figures such as Florence Nightingale, would paint an extremely unfavourable picture leading to demands for reforms.

Whilst the Treaty of Paris marked an important step, with all sides recognising the need for a peaceful solution, the logistics of competing interests in negotiations made it more difficult to put into practice.

The main agreement did manage to create some tangible guidelines which included forcing Russia to demilitarise the Black Sea. This agreement was between the Tsar and the Sultan who maintained that no arsenal could be established on the coastline. For Russia this clause in particular proved to be a major blow, weakening its power base as it no longer could threaten the Ottoman Empire via its navy. This was thus an important step in scaling down the potential for escalating violence.

In addition, the treaty agreed the inclusion of the Ottoman Empire into the Concert of Europe which was essentially a representation of the balance of power on the continent, instigated back in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna. As part of this, the European powers promised to comply with its independence and not compromise any Ottoman territory.

Russia on the other hand was forced to return the city of Kars and all other Ottoman territory which it had taken into its possession. The principalities of Wallachia and Moldovia were thus returned as Ottoman territory, later granted independence and eventually turned into modern-day Romania.

Russia was forced by the treaty to abandon its claim of a protectorate for Christians living in the Ottoman Empire, thus discarding the very premise which engaged Russia in war in the first place. In exchange, the alliance of powers agreed to restore the towns of Sevastpol, Balaklava, Kerch, Kinburn and many other areas back to Russia which had been occupied by the Allied troops during the war.

A major consequence of this agreement was the reopening of the Black Sea for international trade and commerce. The importance of resuming trade was a major consideration for all involved, so much so that an international commission was created on the premise of establishing a free and peaceful navigation of the Danube River for the purpose of commerce.

Apart from resuming trade, the countries involved were forced into a period of reflection; with an unhappy general public, high death toll and little to show for it, leaders needed to show they were willing to make changes. This was particularly pertinent for Russia which suffered terribly, losing around 500,000 of its troops. The Crimean War thus instigated an era of self-evaluation in Russia which threw off the shackles of archaic traditions and embraced modernisation.

Upon the death of Nicholas I, Alexander II became Tsar, who by comparison was liberal in his views and approach. A wave of reforms followed with the momentous decision to abolish serfdom and address issues such as its failing economy. It was at this moment that Russia would embark into a new age where educated elites would pause in a moment of retrospection, unleashing as they did so an era of creativity characterised by the great figures of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Russia took its defeat as an opportunity to resolve internal problems.

Meanwhile, Crimea was significant for Britain as it marked one of its first military interventions in Europe for forty years. The repercussions for Westminster would be massive as the portrayal of the war in British media allowed the public for the first time to receive information day-by-day about the carnage abroad. Information that many would have wanted to keep quiet was available, the needless tragedy of the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade resonated strongly with a disaffected British population.

The Crimean War had ended favourably for Britain and members of its fellow alliance, however its unpopularity had led to a change of leader with the Earl of Aberdeen being forced to resign via a no confidence vote in 1855. The new Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston was the preferred choice. With the increased accessibility of information and more awareness of foreign policy, the people would demand peaceful solutions.

As part of this new change under Palmerston’s government, an inquiry was launched in order to investigate the disastrous set of events. The report concluded that the government had been responsible for not allowing adequate supplies as well as blaming senior members of the Armed forces for certain delays.

The investigation also made important headway with the evolution of modern nursing practices, prompted by the work of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole who individually were improving the sanitation levels of field hospitals at Crimea. Lessons were there to be learnt for all governments; people were dissatisfied with leadership and a new approach needed to be found.

The Treaty of Paris forced nations to address issues both internal and external. France and Britain would remain committed to reinforcing and stabilising the Ottoman Empire as much as possible in order to restore balance. This would be hard to achieve, especially with the rising tide of nationalism in Ottoman territory which threatened the Empire’s very existence.

The inclusion of the Ottoman Empire into the sphere of European influence was seen as essential for solving the “eastern question”, however, the Treaty of Paris did little to address this conundrum. The treaty simply affirmed Turkey’s crucial role in European peace but was not able to prevent conflict from ensuing once more. The Ottoman Empire would eventually fall in 1914.

More widely, the Crimean War saw the balance of power change hands in Europe. Whilst Russia suffered a major defeat, Austria, which had chosen to remain neutral, would find itself in the coming years at the mercy of a new rising star, Germany.

Under the leadership of Bismarck, who took advantage of fraught relations, new strategy for survival emerged. Austria would end up uniting with Hungary in a monarchical empire. Meanwhile, Sardinia, a participant in the alliance at Crimea would intervene in Italian affairs, ensuring that a united nation of Italy would emerge out of the territorial chasms of Europe.

Traditional empires were now under threat, with Britain and France sensing the urgency and need to maintain a grip on affairs. The Crimean War highlighted how difficult it was to keep a balance of power in Europe. The end of the war resulted in a new era of relations, a new way of doing things; the old traditional empires stretched over continents gave way in Europe to the nation-state. Change was coming.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.