If delivering mail now seems to be a mundane and regulated activity, there are plenty of stories that show this not to have been the case historically.

Before the arrival of speedy mail coaches, with railways puffing along hard on their heels and quickly overtaking them, drama often accompanied the delivery of packages and letters.

Carriers and packhorse trains struggled through mire and snow to bring goods and news to remote locations; bandits and highwaymen lay in wait for them on lonely heaths and in dense woodland. Mail coaches were stuck in snow drifts and their crews sometimes died still desperately attempting to fulfil their duty. One unlucky coach was attacked by a lioness. Still the mail went through!

The history of postal services in Britain and abroad includes some fine and heroic tales. There are few stories to compete with that of the capture of the Jeune Richard by the packet ship Windsor Castle in 1807. As their name suggests, packet ships were vessels that carried packets and other post. Like the mail coaches, they were mostly not owned by the Royal Mail, but independent operators commissioned to carry the mail by special contract. They would carry other items and passengers too; indeed, they had to, because the income from the postal services was not high. A few, it is said, turned to smuggling when times were hard.

Packet ship captains working for the Royal Mail carried an immense amount of responsibility. The contracts stipulated among other things that there should be no involvement with fraudulent deliveries, and that the captains had to ensure their vessels did not fall into the hands of Britain’s enemies. Since deliveries often included transferring bullion across the sea to London, the risks were high. The packet service ships flew their own flag which bore the classic image of a rider blowing a posthorn. This was known as the Post-Boy Jack.

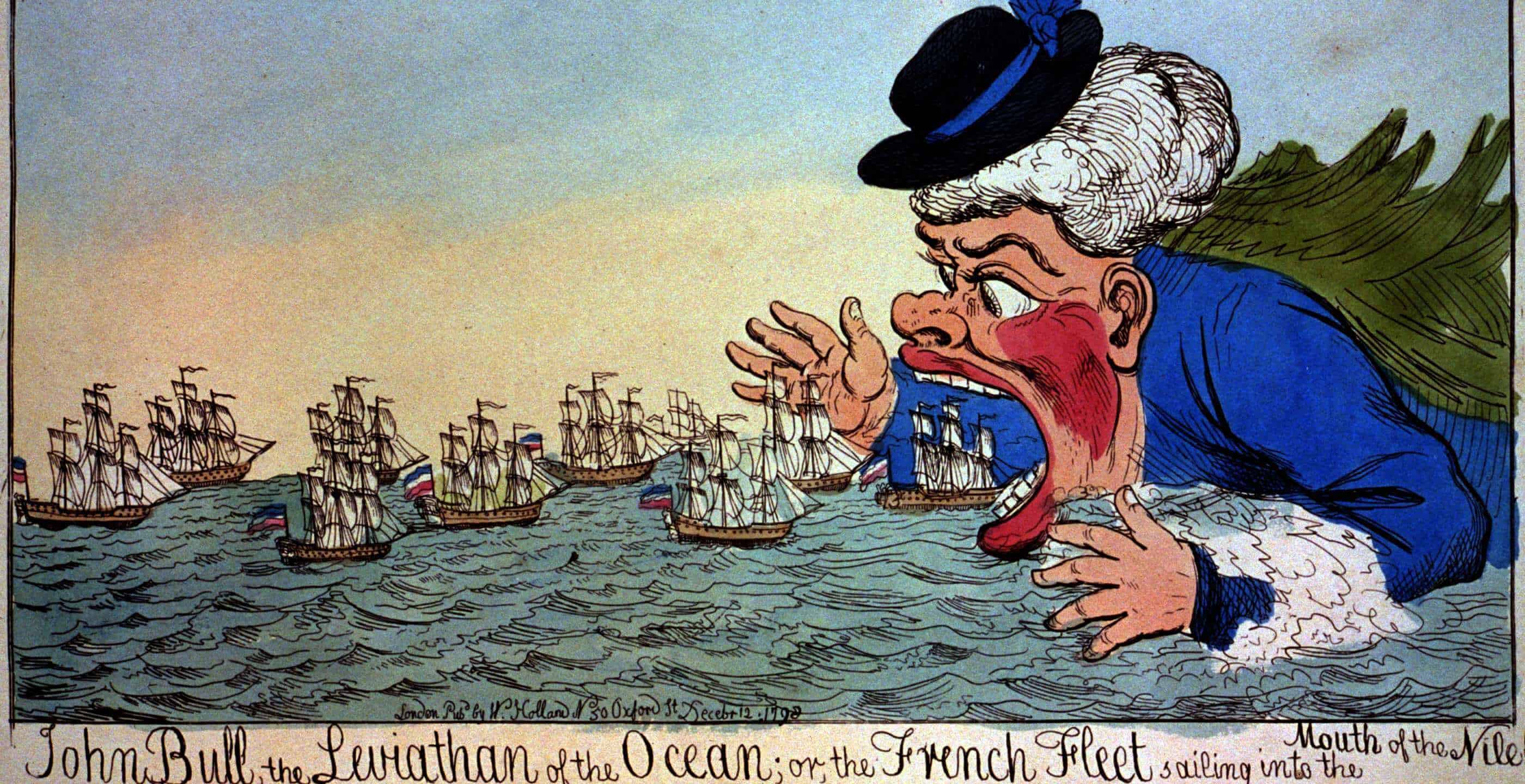

The bravery of their captains and crew was second to none. Not long before the encounter between the Jeune Richard and the Windsor Castle, another packet ship, the Lady Hobart, had overcome a French privateer before coming to grief on an iceberg. The war with Napoleon was at its height and packet ships were an obvious target for the French vessels.

The packet ship Windsor Castle, captained by William Rogers, was on its way to the West Indies on 1 October 1807 when, nearing Barbados, a ship began to close the distance between them. This turned out to be the French privateer Jeune Richard, a larger, faster vessel better equipped with guns and crew. The Windsor Castle carried a crew of 28 men and boys, with six 4-pounder guns and two 9-pounder carronades, a type of cannon produced at the ironworks in Carron, Stirlingshire, Scotland. This was the largest ironworks in Europe and probably the world at that time, and the carronades were endorsed by both the Duke of Wellington and Admiral Horatio Nelson.

However, these short-barrelled, large calibre guns did not compare with the six long 6-pounder guns and a mighty long-barrelled 18-pounder gun carried by the Jeune Richard. With a crew of 92, the Jeune Richard outnumbered the Windsor Castle more than three to one. Despite this, Captain Rogers prepared to engage with the French ship, and also, as the captain’s last resort, to sink the Windsor Castle if necessary so the post would never be taken.

As soon as it was close enough, the Jeune Richard opened fire. The Windsor Castle responded in kind. The French privateer called on Rogers to surrender and he refused. Getting alongside the packet ship, the men of the Jeune Richard attempted to get on board using grappling irons. They met with a fierce defence of pikes during which several of the privateer’s crew died. When it became clear the crew of the packet were not going to give in easily, the Jeune Richard attempted to move away from the Windsor Castle, but the two were now firmly attached to each other.

Against all odds, and using only one of the carronades on deck loaded with a mixture of shot, Rogers’ crew managed to keep the French from boarding the packet. Then, incredible though it appears now, Rogers leaped on board the Jeune Richard with just five of his men, fought off the French gun crews, and drove the whole of the privateer’s crew below decks, where he and his men held them prisoner, bringing them up individually to secure them in chains. The entire engagement had taken less than three hours.

Even more incredibly, the Windsor Castle suffered just three fatalities and ten other casualties, while the privateer had lost twenty-one men and over thirty were injured. Captain Rogers sailed into a British port with the French ship as a prize.

The response, as can be imagined, was overwhelming. The sensational story ran for weeks and months in newspapers and journals, and subscriptions were raised for Rogers and his men. It appears that Rogers was at the time only the acting captain of the ship, and Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane wrote to the Admiralty to recommend Rogers for a permanent post as captain of a packet ship. Not only did William Rogers receive his permanent post, but he was also given the Freedom of the City of London.

The remarkable determination and bravery of the captain and crew of the Windsor Castle made a popular subject for artists of the period. Over two hundred years on it still seems an extraordinary outcome against all the odds. The mail must get through!

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 29th January 2024