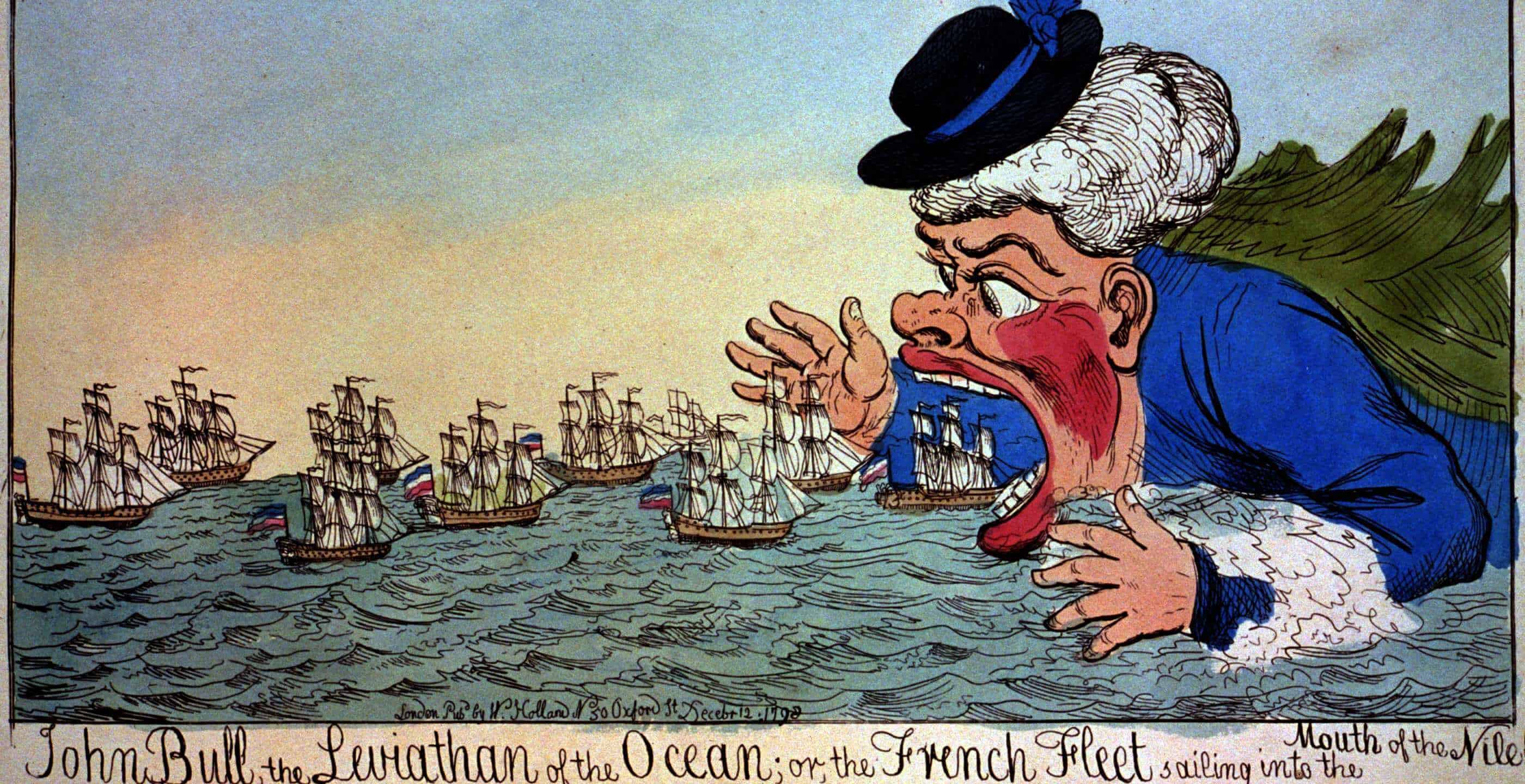

During the Age of Sail, epic naval battles were fought which distinguished the career and characters of some of Britain’s most recognised naval heroes. Whilst the era was defined by victories and spoils of war, with ships commanded by captains made famous by heroic deeds, a lesser known but equally important cog in the naval machinery included young boys who populated the crew of warships known as powder monkeys.

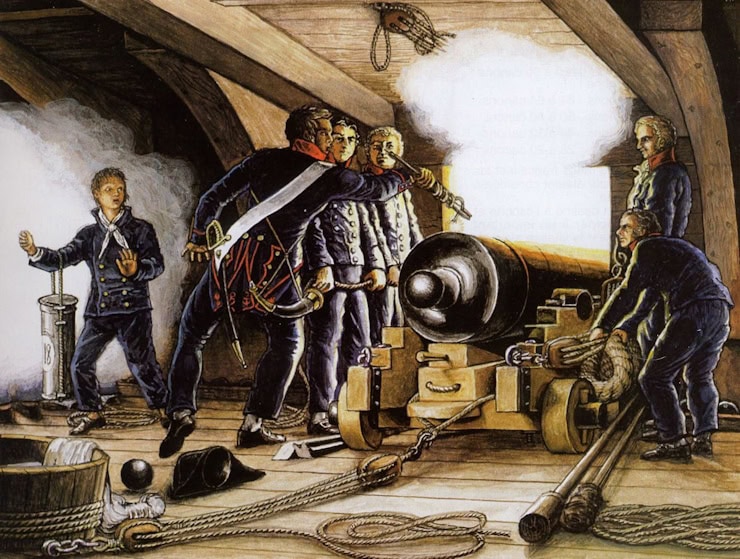

Their role predominantly was to ferry gunpowder to the artillery pieces, a vital and dangerous job given to boys as young as twelve.

Small but fast, boys rather than men, suited such a task as the ships were short on space and their height gave them some protection from being shot at by enemy ships.

Despite the valuable role they played by ferrying gunpowder from deep within the powder magazine in the ship’s hold to the artillery, they did not hold any official position or naval ranking. Many of the boys who fulfilled this role had come from very deprived backgrounds and their parents could not afford to raise them. It was not uncommon to see children on the ship, so much so, that the Marine Society encouraged young boys to join the Royal Navy. In return, the boys would get a bed, clothes and a somewhat basic education.

The Marine Society was set up by a philanthropist called Jonas Hanway who had ideas about dealing with the great number of orphans who plagued the city streets at the time. The plan was to house the children, give them a rudimentary education before introducing them to the navy as a career path. Over time many thousands of boys passed through this system.

By the end of the eighteenth century, it was estimated that around 500 boys were being sent to the fleet every year.

In many cases the boys who became powder monkeys were victims of ‘Press Gangs’ referred to as Impressment. A type of forced conscription of the period, the boys often fell victim to the gangs who lurked around the ports looking to make up numbers on their ship.

Whilst many boys found themselves in a precarious situation with little or no option but to take up a position on a Royal Navy ship, other young boys were part of a longer tradition which had seen their relatives pass through the same system and serve as sailors. With many looking to follow in the footsteps of their older brothers, fathers and grandfathers, their innocent and naïve sense of adventures saw many of them take their first steps onto a warship.

Permanently severed from their homes, these young boys found themselves thrust into a world of intense combat during the Napoleonic era, with little or no status to speak of; their responsibility was great but their remuneration was non-existent.

The term ‘powder monkey’ was first used as far back as the seventeenth century and continues to be used in some countries today but with new meaning, referring to a technician or engineer specialising in demolition (otherwise known as a ‘blaster’).

The Royal Navy was not the only crew which made use of boys as powder monkeys. Across the Atlantic, the United States had declared its independence in 1776, at which point a formal and structured navy had yet to be established. In the coming years, America would model its infant naval force in the structure and form of the Royal Navy, including its use of powder monkeys.

By 1812, the US Navy decided to impose a ban on using any child younger than twelve, however anyone over that age continued to be used up until the start of the twentieth century.

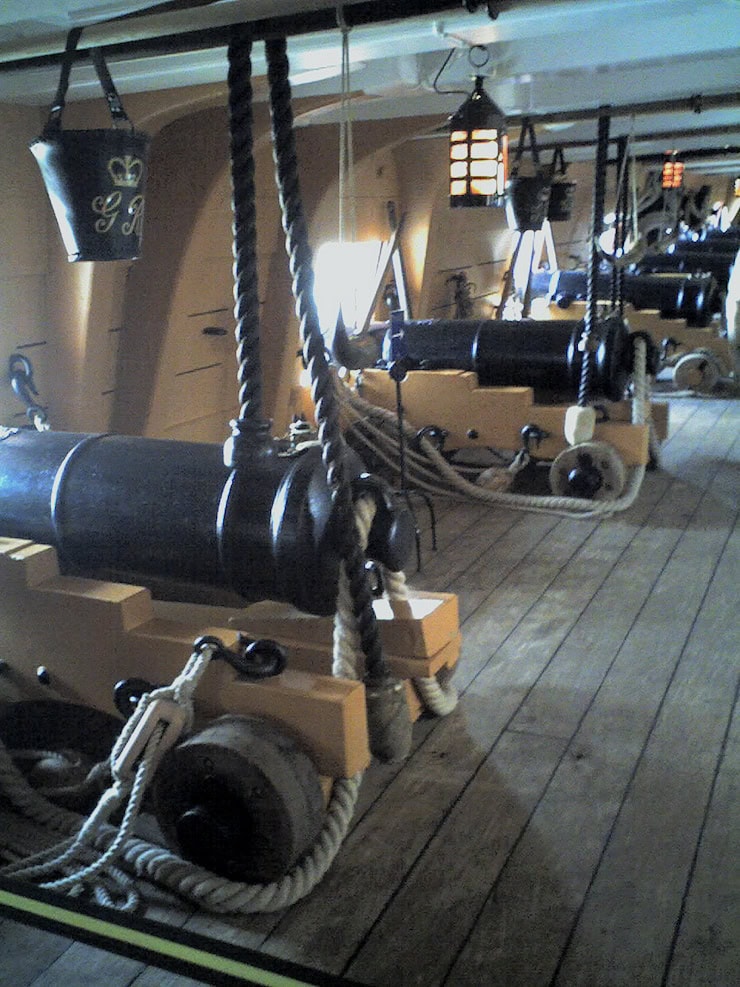

The reality of such work was harsh, unrelenting and extremely important. As a result of its highly combustible nature, gunpowder was kept in a sealed copper-lined chamber referred to as a magazine and was kept below the waterline, thus necessitating a perilous journey back and forth for the powder monkeys who would carry a cartridge of powder to their assigned artillery. Under fire, such a task was relentless and volatile as artillery needed to be loaded at a steady pace to outmanoeuvre the enemy.

At the very heart of naval victories out on the high seas was the skill and success rate of the powder monkeys ability to transport the gunpowder safely to and fro at speed and without error, thus making them an extremely valuable member of the ship’s crew, determining success or failure for the fleet.

Another gruesome aspect of their work included the horrific injuries they could receive whilst undertaking their role. All types of severe and macabre injuries were experienced during the heightened tensions of the Napoleonic era of naval warfare. Those who managed to escape maiming would have undoubtedly witnessed the grisly and horrific fate of their compatriots, powder monkey peers and other members of the crew, a repugnant sight for any man, let alone a child.

Depending on the demand for artillery, in some instances and only rarely, women performed the task of the powder monkeys. Meanwhile, any battle which ensued for a significant period of time would have required anyone to lend their hand to such a task under demanding conditions.

The number of powder monkeys depended naturally on the size and artillery capabilities of the ship itself. Many of the leading ships in the fleet would have at least one hundred guns and it would not have been uncommon to see around fifty boys on large warship.

Under the regulations of the Royal Navy, powder monkeys would have to be at least thirteen: if not, they were permitted to be younger if accompanied by their fathers. In many cases such stipulations were not adhered to and in some instances boys as young as eight were out on the high seas.

This hash reality, in the context of the day, did not appear severe. Whether out at sea or on dry land, children were forced into work at an incredibly early age, whether as an apprentice, operating in a factory or working as a powder monkey on a vessel.

A great deal was expected of these young boys, so much so that in a short period of time they would acquire a great deal of experience, lending their hand to a number of different tasks on board the ship. This included learning the ropes, quite literally from the other sailors as they learnt to scale dizzying heights and acquire balancing skills when managing the sails.

Their young age was most definitely not seen as an impediment to acquiring the necessary skills of seamanship. Their power and contribution was needed and if they were to survive such an inauguration, their acquired skills and experiences would be essential for the manpower and future of the Royal Navy.

The Age of Sail was a significant time which defined the successes and failures of nations. With the growing threat of Napoleon, the Royal Navy found itself on the front line of defence, seeking to not only defeat its enemy but secure victories and expansion of its own global interests.

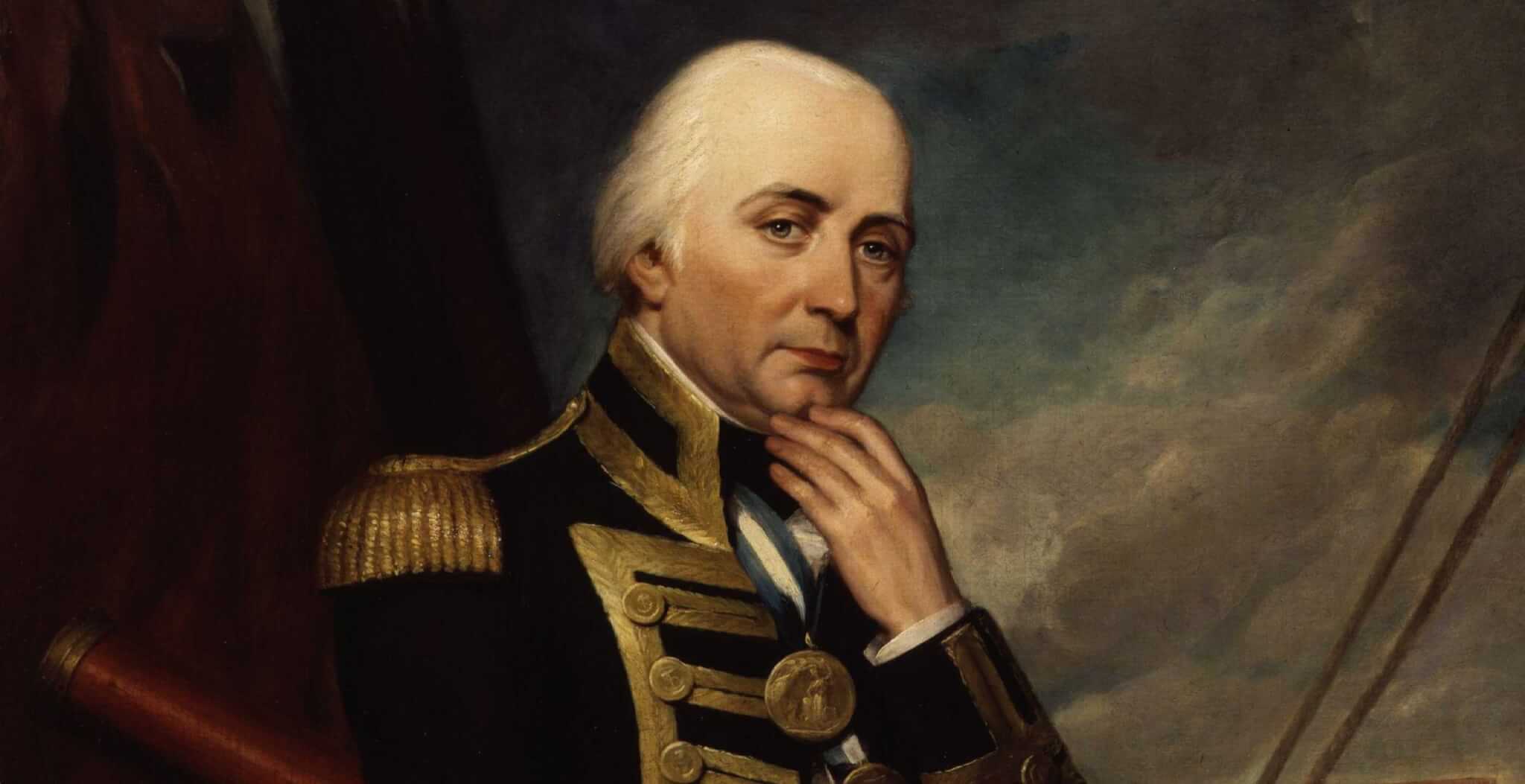

In order to enable such victories, the eighteenth century required not only great and experienced admirals to go down in the annals of history, but also young boys, learning on the job, participating as a group effort to outmanoeuvre and outgun their opponents, thus making the powder monkeys an undervalued but highly significant part of Britain’s naval victories.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 13th January 2025.