“We place absolute confidence in the Titanic. We believe that the boat is unsinkable.” – Philip Franklin, Vice-President of White Star Line, owners of Titanic.

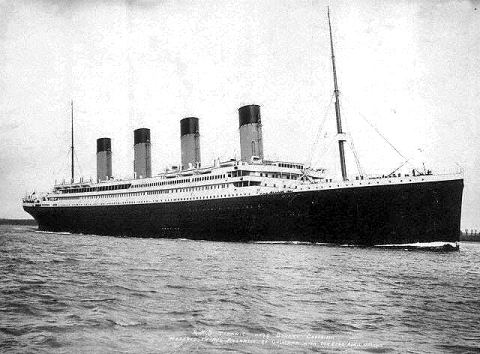

When she set sail across the Atlantic on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England to New York City on 10 April 1912, the RMS Titanic, at 52,310 tons, was the largest passenger steam ship the world had ever seen.

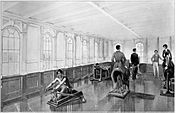

One of the White Star Line shipping company’s three sister ships known as the Olympic-class ocean liners, which also included the Olympic and the Britannic, Titanic was billed as the most luxurious ship to operate on the North Atlantic. Indeed passengers in first class were able to enjoy a gym, plunge pool, Turkish bath, barber’s shop, electric lifts, library, restaurant and café amongst other amenities. No expense was spared to create a high-tech, luxurious backdrop for those prepared to pay for the privilege of crossing the Atlantic at speed and in style.

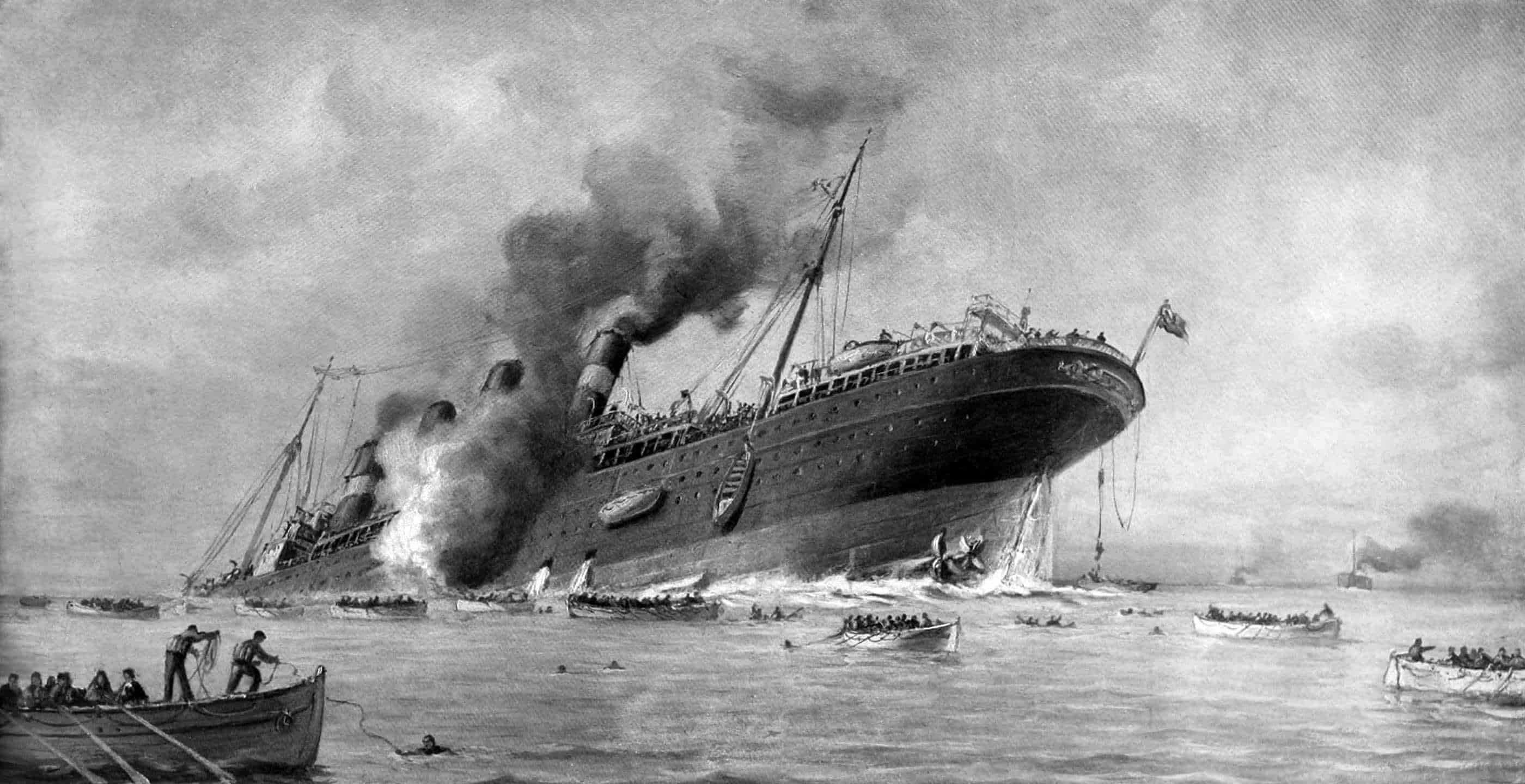

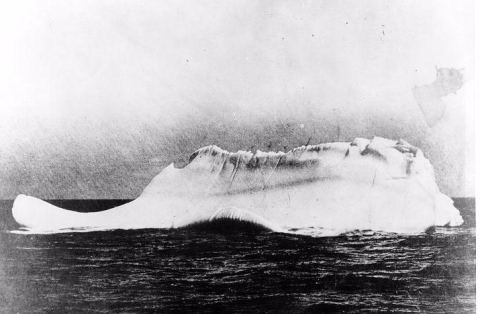

However, the widely reported claim that advancements in ship-building and the vessel’s sheer size made her virtually unsinkable, was tragically refuted four days later. At 11.40pm on 14 April 1912 the ship struck an iceberg, sinking without a trace less than three hours later at 2.20am on 15 April and claiming the lives of 1517 of the ship’s 2223 passengers in what was to become the most enduring image of maritime tragedy of all time.

Titanic’s demise has long since served as a cautionary tale of the battle between man and nature. But why were so many lives lost? Was this a tragic unpreventable accident or did the fault lie in human error?

Titanic’s speed

Having received numerous warnings of icebergs in the vicinity, Titanic’s Captain, Edward J Smith, altered the ship’s course to take it further south than originally planned. His years of experience at sea suggested little risk of ice so far south at that time of year. However, Captain Smith did not alter Titanic’s speed in response to the warnings and many have suggested that the iceberg could have been avoided if the ship had been travelling at a slower pace, as the mighty vessel had little time to avoid the berg, hitting it approximately 37 seconds after it was first sighted by lookouts.

It has been suggested by some surviving passengers that Captain Smith was pressured into travelling as fast as possible by White Star Line’s managing director, J. Bruce Ismay, who was keen to arrive in New York ahead of schedule to encourage positive press about the new ship. It has also been argued by some historians that the speed at which the ship was travelling contributed to the speed at which it sank, and that the change in route meant that rescuers struggled to locate the ailing ship.

Weather conditions

Whilst the decision to continue travelling at high speed has long-since been criticised, it was the maritime custom of the day to depend on lookouts in the crow’s nest and watchmen on the bridge to warn of on-coming icebergs in time for a change of course. Unfortunately, the lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee were hampered by their lack of binoculars (said to have been accidentally left behind in Southampton) and the unusual weather conditions.

Clement winter temperatures were responsible for the high number of icebergs in the North Atlantic that April, and as the ship entered an area of high pressure, the temperature dropped to the freezing mark and the sea was calm and still. While such a placid stretch of sea is now known to be a sign of nearby ice, the lack of crashing waves coupled with no moonlight to act as a guide meant that visibility was exceptionally poor. As a result the warning call from the crow’s nest came too late.

Watertight compartments

Considered to be at the forefront of technological advancement, the Titanic housed sixteen watertight compartments on the underside of the ship which could be closed electronically if water entered them, preventing the ship from sinking. Whilst the compartments were closed immediately after impact with the iceberg on 14 April and did slow the progress of the water that began to flood the ship, six of the sixteen compartments were completely flooded, which made the ship too heavy to remain afloat.

It had been calculated by the ship’s engineers that should four or less compartments be flooded by a head-on collision, or the two central compartments be compromised by a shunt from another boat, Titanic would remain afloat. Sadly, in trying to turn the boat away from the fast approaching berg rather than hit is head on, First Officer Murdoch’s order to turn “hard-a-starboard” (a sharp left) meant the ship suffered irreparable damage.

The iceberg tore into six of the compartments in the brief 10 seconds of impact, allowing water to pour into the ship at a much faster rate than the ship’s pumps could handle. On inspection of the damage, Titanic’s engineer Thomas Andrews confirmed to the shocked Captain Smith that the ship would definitely sink and would do so in about two hours time.

Interestingly though, ultrasound analysis of the wreck in 1996 has shown that rather than renting a large tear in the side of the boat as is often depicted in Titanic mythology, the impact of the iceberg hitting the bow of the boat caused stress to the rivets holding the hull plates together, causing the plates to separate and allowing water to flood into the ship.

A photo of the iceberg presumed to have been hit by the Titanic. Debris and bodies from the sunken ship were found nearby and it was alleged that the berg was marked with red paint from a ship’s hull.

The Californian’s failure to react

When Titanic began to break apart and plummet beneath the waves less than three hours after the initial impact with the berg, those remaining aboard the ship were either dragged down with her or tossed into the icy water below, where should they have survived falling debris, hypothermia began to set in within minutes.

Having picked up the first wireless distress signals from the ailing vessel just after midnight, the RMS Carpathia raced at maximum speed to save the Titanic, which was 58 miles away, picking up the first of the lifeboats at 4.10am, nearly an hour and a half after Titanic sunk.

But what of the SS Californian, which was 19.5 miles away, and to whom the ailing ship and her distress flares were clearly visible? Having received the wireless transmission that the Californian had stopped for the night because of ice, Titanic’s senior wireless operator Jack Phillips reprimanded the Californian’s wireless operator Cyril Furmstone Evans for interrupting him. This was because Jack and his fellow wireless operator were employed first and foremost to provide first class passenger messages to and from the shore, and had a backlog to transmit, so ice warnings were not considered a priority. Having tried his best to deliver his message Evans, the sole wireless operator on the Californian, retired for the evening.

When officers aboard the Californian spotted a number of distress flares coming from the Titanic in the hours before she sank and later noticed that the ship appeared to be leaning sideways at an odd angle, they awoke their Captain, Stanley Lord, several times to inform him of the strange occurrences. Lord told his men to signal the ship with a Morse code lamp, which they did repeatedly between 11:30 pm and 1:00 am, receiving no response from Titanic. It was later discovered that the lamp used by the Californian could only be seen at a distance of 4 miles, so it would not have been visible to those aboard the Titanic, nearly 20 miles away.

That no one thought to wake the Californian’s wireless operator until 5.30am that morning was the subject of numerous inquiries after the Titanic sank, since it was only then that Evans was alerted to the loss of Titanic by a wireless operator on a nearby ship, and the Californian arrived at the site of the disaster to see that all survivors had long since been rescued by the Carpathia. Though no charges of negligence were brought against Lord or his crew, publically he was vilified for the part he played (or rather did not play) in the tragedy.

Inadequate lifeboat provision

Despite numerous contributing factors, the foremost reason for the loss of life aboard the Titanic was the lack of lifeboat provision, as the vast majority of deaths were caused by hypothermia while passengers struggled to keep warm in the -2°C water. To allow room for the lavish aspects which were to set Titanic apart from her competitors, Ismay had decreed that there should be only 16 lifeboats on board, which was the minimum number permitted by the regulating body, the Board of Trade. At the time, the Board of Trade based the number of lifeboats required on a vessel’s tonnage as opposed to passenger numbers. 16 lifeboats would, at capacity, only carry 1,178 passengers, but it was felt that the Titanic’s safety features would allow plenty of time for rescue by any nearby vessels and lifeboats would only be needed as a means to ferry passengers between ships. In addition, many passengers believed the hype of the ‘unsinkable’ ship, and a number of lifeboats left the ship less than half-full following the impact with the iceberg as passengers felt the safest and most comfortable option was to stay on the ship and refused to climb aboard the lifeboats. As the table below shows, while the call was for women and children first, priority was awarded on a class basis and the poorer passengers, particularly the men in third class, had little chance of survival.

| Category | Number Aboard | Number of Survivors | Percentage Survived | Number Lost | Percentage Lost |

| First Class | 329 | 199 | 60.5% | 130 | 39.5% |

| Second Class | 285 | 119 | 41.7% | 166 | 58.3% |

| Third Class | 710 | 174 | 24.5% | 536 | 75.5% |

| Crew | 991 | 214 | 23.8% | 685 | 76.2% |

| Total | 2223 | 706 | 31.8% | 1517 | 68.2% |

The number of Titanic passengers lost and surviving

In response to the Titanic death toll, the Board of Trade swiftly changed maritime regulations, particularly in relation to lifeboat requirements, and inquiries held in Britain and the United States lead to the introduction of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) – an international maritime safety treaty – two years later, which is still in place today.

The human impact

Of the 706 people who survived the disaster, there were some joyful reunions and the odd happy tale, such as the ship’s baker, who – having kept himself refreshed with a generous amount of whisky whilst helping with the evacuation efforts – was found alive in the freezing waters having been insulated from the cold by the amount of alcohol in his system.

However, though thankful to be alive, many survivors were irrevocably affected by their experiences. Indeed a number, such as Colonel Archibald Gracie who provided one of the key accounts of the disaster, never fully recovered from the experience and passed away shortly afterwards. For those who had lost everything on the Titanic, whether it be all their worldly goods or (in the case of the families of lost crew members) their only source of income, the overwhelming tragedy struck a chord with the public and charitable donations poured in.

The public’s fascination with the tragedy has not waned in the 100 years since Titanic sank, with survivors finding themselves becoming minor celebrities. Indeed one of the surviving stewardesses aboard the Titanic, Violet Jessop, came to the public’s attention when it was discovered that she had the dubious honour of being the only person to endure a similar fate on Titanic’s sister ships Olympic and Britannic, surviving the sinking of the latter in 1916 and the former’s collision with the British warship HMS Hawke in 1911. But perhaps the most famous of all the Titanic survivors was Millvina Dean, the last remaining survivor until her death at the age of 97 in May 2009, and at just over 2 months old, the youngest person on board Titanic.

Violet Jessop (left) during her time as a nurse on Her Majesty’s Hospital Ship Britannic and Millvina as a baby (far right) with her brother Bertram, who also survived the sinking of the Titanic

But as with so many tragic tales, both heroes and villains have been cast. Those such as Captain Lord and J. Bruce Ismay – and indeed any men who were said to have boarded lifeboats leaving women and children behind – had to contend with blame and criticism for the rest of their lives as the memory of that fateful evening was rekindled by countless books, television shows, films and exhibits worldwide.

Published: 1st April 2022.