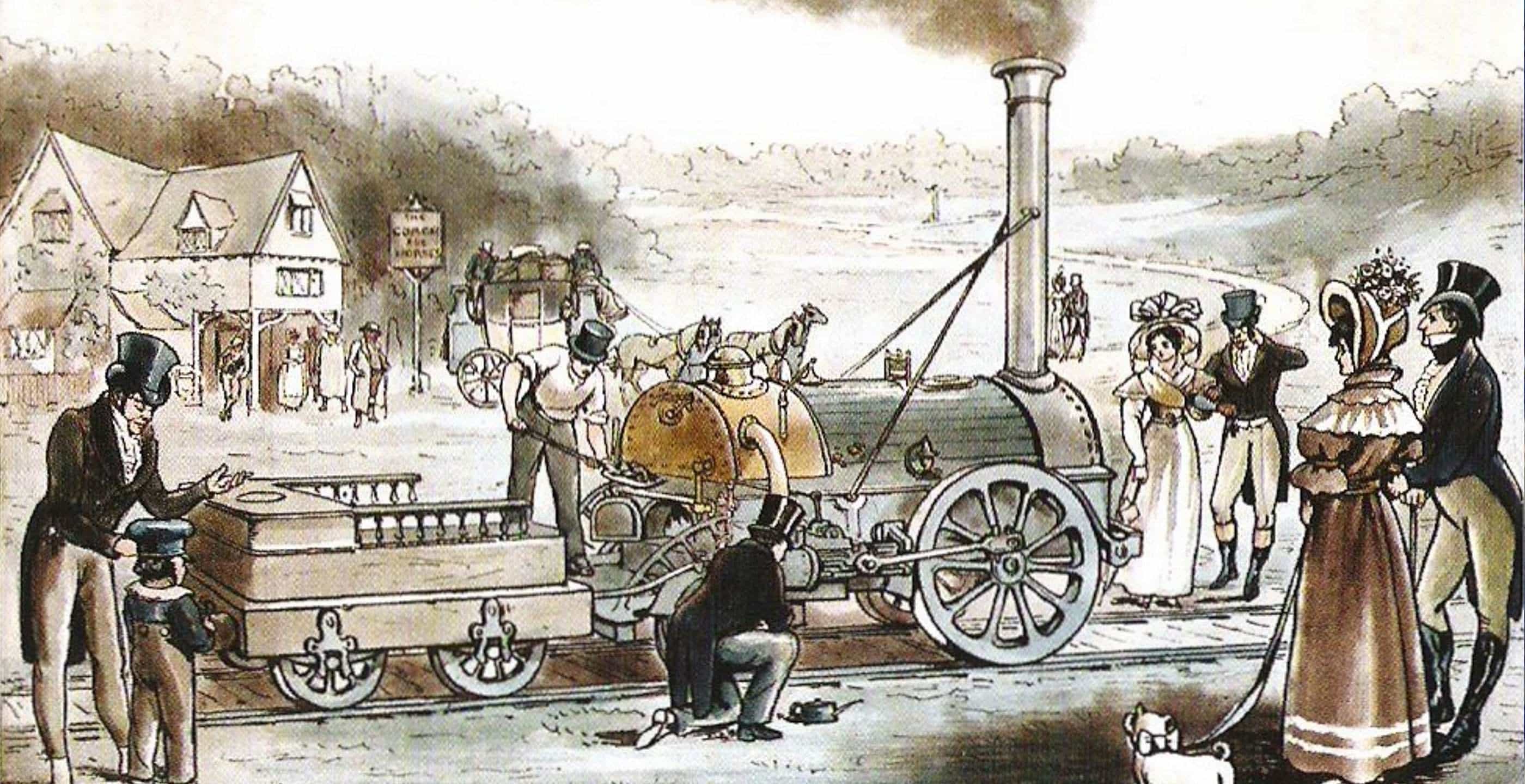

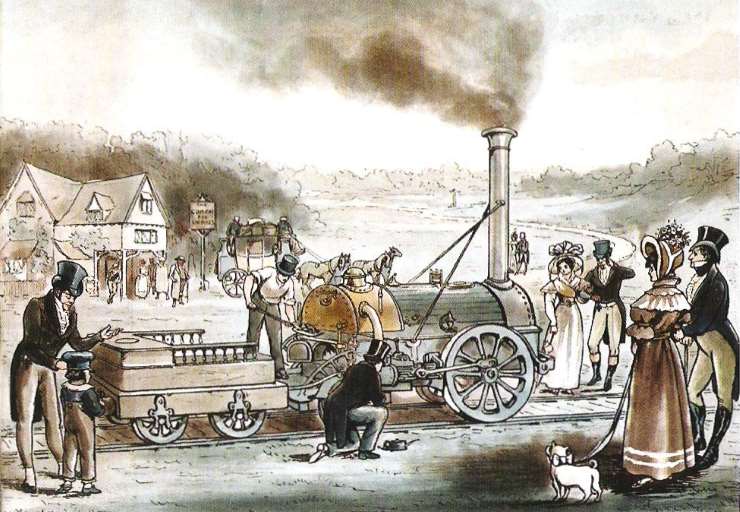

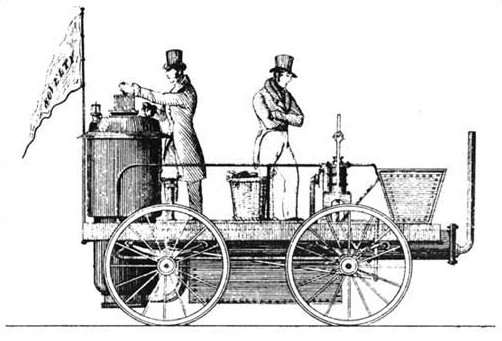

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened on 15th September 1830, beginning a new era in passenger transport. Images of those early locomotives, great boilers on wheels fuelled by coke and driven by men in stovepipe hats, entered the history books. Today, those images still evoke the spirit of the age.

With seven other decorated engines also on parade, including his own famous “Rocket”, George Stephenson’s locomotive “Northumbrian” proudly drew an ornate carriage occupied by the Prime Minister the Duke of Wellington and his party. With Stephenson himself as driver, the “Northumbrian” reached speeds of a terrifying 25 miles an hour along the track between Edge Hill near Liverpool and Parkside to the north of Warrington!

While it must have seemed like the dawning of a new age to the enormous crowds gathered along its route, the Liverpool and Manchester was the culmination of centuries of development. Railways had begun as wooden waggon ways or tramways carrying trucks and tubs drawn by horses or pushed and pulled by people. Now, flanged-wheel carriages drawn by steam locomotives were flying along double-tracked metal rails between two of the UK’s most important commercial centres.

Stephenson must have felt justifiable pride in his achievement, because he, more than anyone else, knew the political wrangling, chicanery, back-stabbing and epic failures that had littered the path to success before the first piece of track was even laid.

A master engineer who had served his time developing steam engines for collieries in his native north-east, Stephenson had applied his skills to making important improvements to both stationary and locomotive engines.

Before joining the Liverpool and Manchester Railway as engineer, Stephenson had already gained experience of commercial railway development. He had been chief engineer on the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which, although not primarily a passenger carrying concern, had transported its directors and 21 waggon loads of people, as well as twelve goods waggons, behind a single locomotive on its inaugural journey in 1825.

Stephenson and the directors of the Stockton and Darlington had to fight vested interests in the form of stagecoach owners and would-be canal developers, as well as opposition from local landowners. They also had to contend with the fears of ordinary people who only saw job losses and all the other frightening changes that accompanied new technology.

This terrifying new steam traction simply wasn’t natural! It created dangerous smoke and fumes that polluted the environment! The land would be ripped up, horses would be terrified – in fact, they would quickly go extinct now that the railway had stolen their jobs – and heaven knows what the effect of travelling at speeds of 20 miles an hour or more would do to the insides of the average human.

And so, when Stephenson was hired by the directors of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway to survey and draw up the route of the proposed new line, he had some idea of what to expect. If anything, opposition was even more fierce on the western side of the Pennines, and getting the necessary bill through Parliament proved no easy affair. Then there was the issue of laying the track across the notorious bog of Chat Moss, where most of the naysayers said he was sure to come to grief.

Having successfully dealt with all the opposition as well as Chat Moss, Stephenson found himself facing one last obstacle. Some of the directors were suggesting that the new railway for which he had fought so hard should be powered by stationary engines.

This proposal would have involved the placing of fixed engines at intervals along the whole length of the track, with cables to haul along the coaches and waggons. It’s interesting to imagine how different a trip between Liverpool and Manchester would have been if the directors had won!

Stephenson was prepared to fight for locomotive power. It was agreed that there would be a competition to prove the supremacy of locomotives and a prize of £500 was offered to whoever won a proposed trial at Rainhill. The locomotives would be demonstrated over a one and half mile section of the railway, hauling three tons for every ton of the loco’s own weight. Other terms and conditions, as they say, also applied.

The floodgates opened and the directors nearly suffocated under the weight of the proposals that poured in from all over the world, “each recommending an improved power or an improved carriage”. The trials were finally set for October 1829.

The Stephensons, George and his son Robert, went to work on their proposed engine in their now famous workshop in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. George, of course, was also engineer to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and had plenty of work to do on the line itself, so most of the work of constructing the engine was on Robert’s shoulders.

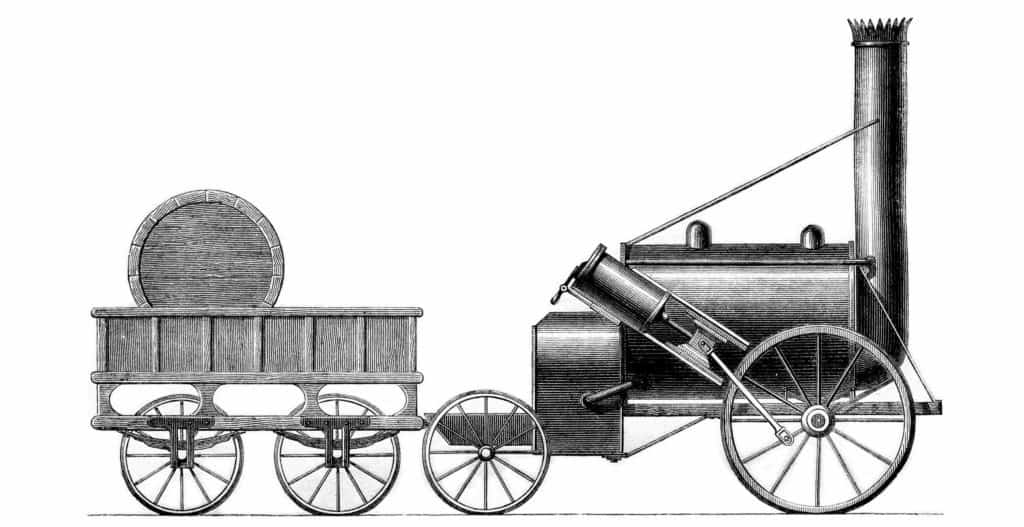

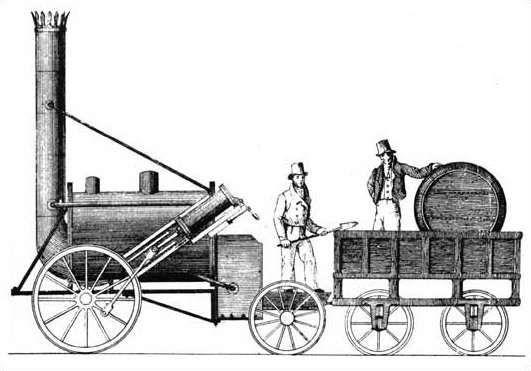

Their engine, which would go down in history as the Rocket, was a radical multi-tube boiler construction which passed the heated gas created in the firebox through tubes within the boiler itself. This then exited via the typical tall chimney engine, creating a strong flow of heat driven by the cylinders.

After successful tests, the Rocket was carried on horse-drawn waggons (horses being very much required in railway construction!) across to Carlisle on the west coast, ready to be shipped to Liverpool.

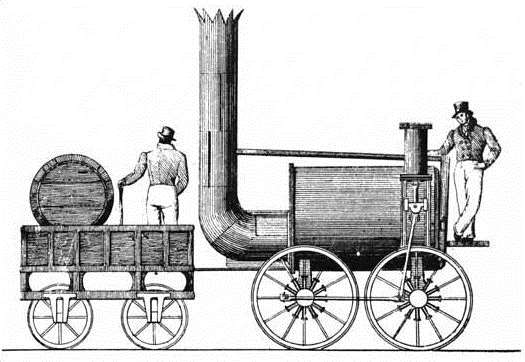

There were four other participants for the finals of the Rainhill Trials, which ran from the 6th – 14th October 1829. One of them was Timothy Hackworth of Darlington, fellow north-easterner and friend to the Stephensons, whose workshop was in fact in his hometown of Shildon in County Durham. His engine was the “Sans Pareil”.

The London engineering firm Braithwaite and Ericsson entered their locomotive, the “Novelty”. From Edinburgh came Burstall’s “Perseverance”. The competitors had all been keeping an eye on what the others were up to – Burstall’s son even travelled from Edinburgh to Newcastle to check on the Stephensons’ progress!

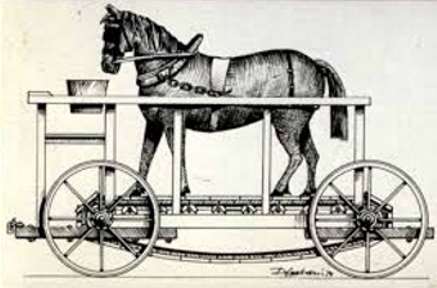

Most eye-catching of all, but sadly eliminated under the Board of Directors’ ruling of “no horses” was Thomas Brandreth’s Liverpool entry, the “Cycloped”. This consisted of two horses walking on a type of conveyor belt to power the wheels of a flat-bed waggon with rails. It seems the Cycloped did turn out for the Rainhill Trials for the entertainment of the crowds. A nice touch in the images of the curiosity is the bucket in front of the horse (only one being shown), providing either horse feed or water. Whether energy was provided by horse or steam engine; fuel and water were always required. The “Manumotive” was also eliminated – two powerful men pulling six passengers in a carriage was definitely against the rules!

The engines from London and Edinburgh were relatively lightweight affairs compared with those of Hackworth and Stephenson. Hackworth was even criticised by one judge for having an overweight engine that also didn’t meet the criteria in other ways. A leaky boiler and other faults meant Hackworth had to withdraw from the competition, but not before a few a few trials in front of the crowd that ended in a spectacular boiler explosion.

The “Novelty”, a beautiful engine, clearly had plenty of speed, if not drawing power, since it reached over twenty-four miles an hour before exploding on 10th October when the bellows burst under steam pressure. The “Perseverance” was badly damaged during its long journey from Edinburgh to Liverpool, but Burstall managed to repair it so that it ran at five or six miles an hour on the track. Eventually though, like Hackworth and Braithwaite and Ericsson, he had to withdraw from the trials.

The finest moment for the Stephenson’s “Rocket” came on the morning of 8th October as the experienced Stephenson crew swung into action like their own well-oiled machine. Drawing a full load of thirteen tons including two waggons carrying stone, the Rocket clocked twenty-nine miles an hour at various points and not only pulled but also pushed the waggons back and forth in a display of showmanship that the crowd clearly loved.

Nearly a year later, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway would be officially opened for business, with national leaders and local officials in attendance. On that occasion the Stephensons’ triumph would be overshadowed by the tragic death of William Huskisson MP, the ardent railway supporter who was also the first victim of a railway accident. On 10th October 1829 at the Rainhill Trials though, there was nothing to mar the success of the Stephensons’ Rocket – the great age of steam had truly arrived!

Miriam Bibby BA MPhil FSA Scot is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant. She is currently completing her PhD at the University of Glasgow.