There have been several false dawns for the airship industry since its heyday during the 1920s and 1930s, but could we be on the verge of a perfect storm for the revival of this beautiful, arcadian and romantic form of flight, due to a number of converging factors? Maybe, just maybe…

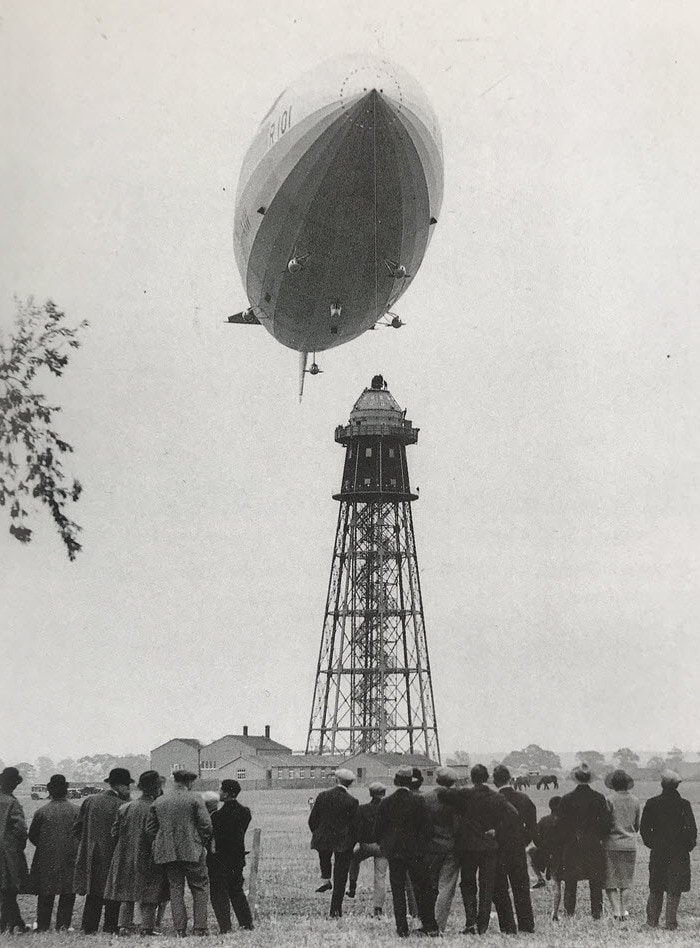

On 4th October 1930, the R101 airship made its much publicised final flight from Bedford’s Cardington Sheds, an event that’s being marked by a new community place-making art project produced by Bedford Creative Arts entitled Airship Dreams, which will culminate in an installation at The Higgins Bedford Museum and Gallery. The initiative celebrates this Golden Age of the Airship, when it was the world’s most advanced form of flight and the fastest mode of global travel. It was also an important military craft used for both surveillance and as a weapon of war. What’s more, Britain was leading the way, with Bedford the home of airship innovation and production.

The R101 was built to fly people in luxury across the globe. At this time, an airship could reach Australia in five days with just three or four short stops, attaining speeds of 80 miles per hour in still air and up to 130 miles per hour under the right wind conditions. Germany was close behind the UK in airship development with the Graf Zeppelin and later the Hindenburg, the Concorde of its day, which flew passengers in style across the Atlantic to New York. However, two disasters would shake public confidence and the airship industry, from which it has never recovered.

En route to India, the R101 crashed tragically in France, killing most of its 54 passengers. Seven years later, the Hindenburg went up in flames. “The R101’s most experienced crew and lead designer, along with the Director of Civil Aviation and the Lord of the Realm who led the project all lost their lives in the crash,” explains Alastair Lawson of the Airship Heritage Trust, a partner of the Airship Dreams project. “The limited investment available at the time due to the Wall Street Crash was then diverted into the aeroplane programme. This fuelled the invention of the jet engine in the 1940s, leaving the R101, Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg behind.”

But was abandoning the airship folly? What benefits would lighter-than-aircraft (LTA) technology (as it’s known among today’s experts) bring in the 21st century and is it still considered a safety threat?

Misguided

Giles Camplin, Chair of the Airship Association, believes it was misguided not to continue to develop the airship. He also says safety levels could not be significantly improved “because it was never dangerous”. “Some 1,200 airships have been built since the first attempt in 1784 and many have impressive safety records,” he explains. “Up until 1933, the Graf Zeppelin (LZ127) made 290 flights covering 330,000 miles, safely carrying 8,000 passengers along with 55 tons of mail and freight. There are other examples, but all were eclipsed by the Hindenburg crash. However, of the 97 people on board, there were 35 fatalities, including 13 passengers and 22 crew, plus an additional fatality on the ground. These are the only paying passengers that have ever lost their lives in airship transport to date.” The R101’s final journey was a show flight carrying guests only.

But surely any craft full of highly flammable hydrogen, used for buoyancy, presents a danger. “Hydrogen actually requires a mix of oxygen to become flammable,” counters Lawson, adding: “What’s more, modern airships use helium rather than hydrogen, which is not flammable at all,” referring to the small number of LTA projects that currently exist.

“There is no doubt that today’s operations are safe, since all types are compliant with airworthiness and operating rules,” confirms Bruce Blake who has been working on airship projects since the 1970s and cites the Zeppelin NT and Hybrid Air Vehicles’ Airlander 10 as two of the better modern examples. However, he describes the industry as currently “virtually dormant”.

Relevant

So, not only are airships now safe and still relatively fast compared to other forms of transport, unlike planes they also don’t require a runway to take off or land, potentially placing international passenger and commercial transport on people’s doorsteps. Furthermore, their environmental credentials are unrivalled, something that is becoming increasingly important as fear over global warming escalates, while the current Covid-19 pandemic has clearly illustrated the air and noise pollution benefits of fewer cars and planes.

“Airships are very quiet and use less fuel during a long journey than passenger planes do just taking off. Current projects are close to developing a completely carbon neutral version and able to fly non-stop for over 70 hours with a crew of just five,” stresses Lawson.

Their almost noise-free nature coupled with the ability to stay airborne for days with a small crew was what made airships ideal for marine military observation operations. The same would still apply today. “They are especially good at surveillance at sea,” says Camplin, “and thus could certainly play a big role in activities such as air/sea rescue, anti-piracy and anti-smuggling, coast guard patrols, fisheries protection, finding underwater ship and plane wreckage, and more.” He also considers airships ideal for a range of leisure and tourism pursuits, such as whale watching and safaris, as they would not disturb wildlife, and for environmentally friendly luxury air cruises. And this would potentially be just the start, because, as Blake is keen to point out, “the technology of modern buoyant aircraft,” as he describes the airship, “remains ‘rooted’ in infancy”.

“As an industry, it could easily grow significantly during the coming three decades,” he says. “But for this to happen, modern designs must be based upon the actual needs of end-users. Included in this scenario, there must be realistic commercial applications and relevant operating companies, driving expansion along the lines of other types of vehicle research, development and manufacturing.”

Although Blake believes a lack of professionalism, realism and good business acumen has dogged the airship industry to date, there is, he says, interest out there among investors. “We are seeing more and more funding opportunities from ‘angel investors’ and venture capital syndicates, plus some real government incentives to encourage innovation.”

Potential

Joining airships among the clouds and applying some blue sky thinking, what other potential “actual end-user needs” could LTA technology meet right now? Lawson has a future vision of the airship as an airborne, movable warehouse. How would the goods be accessed? By drones, of course. This would certainly satisfy consumer demand for faster ecommerce delivery, which is currently restricted by warehouse location. And it banishes any thoughts of airships being just old technology.

One of the biggest issues facing the planet is a lack of space for its constantly growing population. Enter the house airship, akin to the houseboat only airborne and therefore with no ground footprint – and, of course, potentially mobile. So could airships really rule the skies of the future?

“In the 1930s, Britain was a world-leader in LTA technology,” reminisces Camplin. Quickly returning to the present, he continues: “Today, we have stronger materials, better bonding techniques, faster and more reliable means of making complex calculations, and a greater understanding and means of monitoring meteorological phenomena. Plus, we’ve a whole range of other things that previous generations did not have, such as computer simulations, systems monitoring, cost estimating, finite element modelling, and project management. With the right support and investment, Britain would be perfectly placed to pick up where it left off and lead the world again in establishing airships as a highly useful part of transport infrastructure.” And possibly a whole lot more…

Could we be entering a new age of LTA technology driven by environmentalism and further fuelled by the pandemic? It would certainly help prevent climate change and our over reliance on fossil fuels. Or might this just be another Airship Dream?

Airship Dreams is a place-making art project consisting of a programme of exhibitions and events commemorating the 90th anniversary of the final flight of the R101 and celebrating this beautiful, graceful, arcadian and romantic form of flight. The organisers are inviting people across the UK and beyond to share their personal airship connections, family tales and objects. Contributions will be included in programme. More information can be found at the Airship Dreams website while stories can be shared on social media using #AirshipDreams.

About Airship Dreams

Airship Dreams is a place-making art project consisting of a programme of exhibitions and events commemorating the 90th anniversary of the final flight of the R101 and celebrating this beautiful, graceful, arcadian and romantic form of flight.

Bedford Creative Arts (BCA), The Higgins Bedford Gallery, the Airship Heritage Trust and award-winning artist Mike Stubbs have joined forces to launch the project, and are inviting people across the UK and beyond to share their personal airship connections, family tales and objects. Contributions will be included in programme.

About Airship Heritage Trust

Set up in 1985 by the relatives of the 1921-36 airship programme and originally known as F.O.C.A.S (Friends of the Cardington Airship Station). The Trust is a learned society promoting the history of British airships history through its own talks, activities, and displays, as well as partnering with the Higgins Museum, Bedford, the Fleet Air Arm, Yeovilton, and other likeminded organisations to assist with the promotion of lighter than air history. It has a collection of historic artefacts, documents and includes many rare photographs. The AHT records and administers a major source of British airship history.

All photographs by kind permission © Airship Heritage Trust.