Whilst some history enthusiasts may subscribe to English MP and military historian Alan Clark’s view of British military command during the Great War, describing the brave British Tommy as a ‘”Lion led by Donkeys”, Lieutenant-Colonel Ronald d’Arcy Fife (1868-1946) certainly presents a challenge to this interpretation.

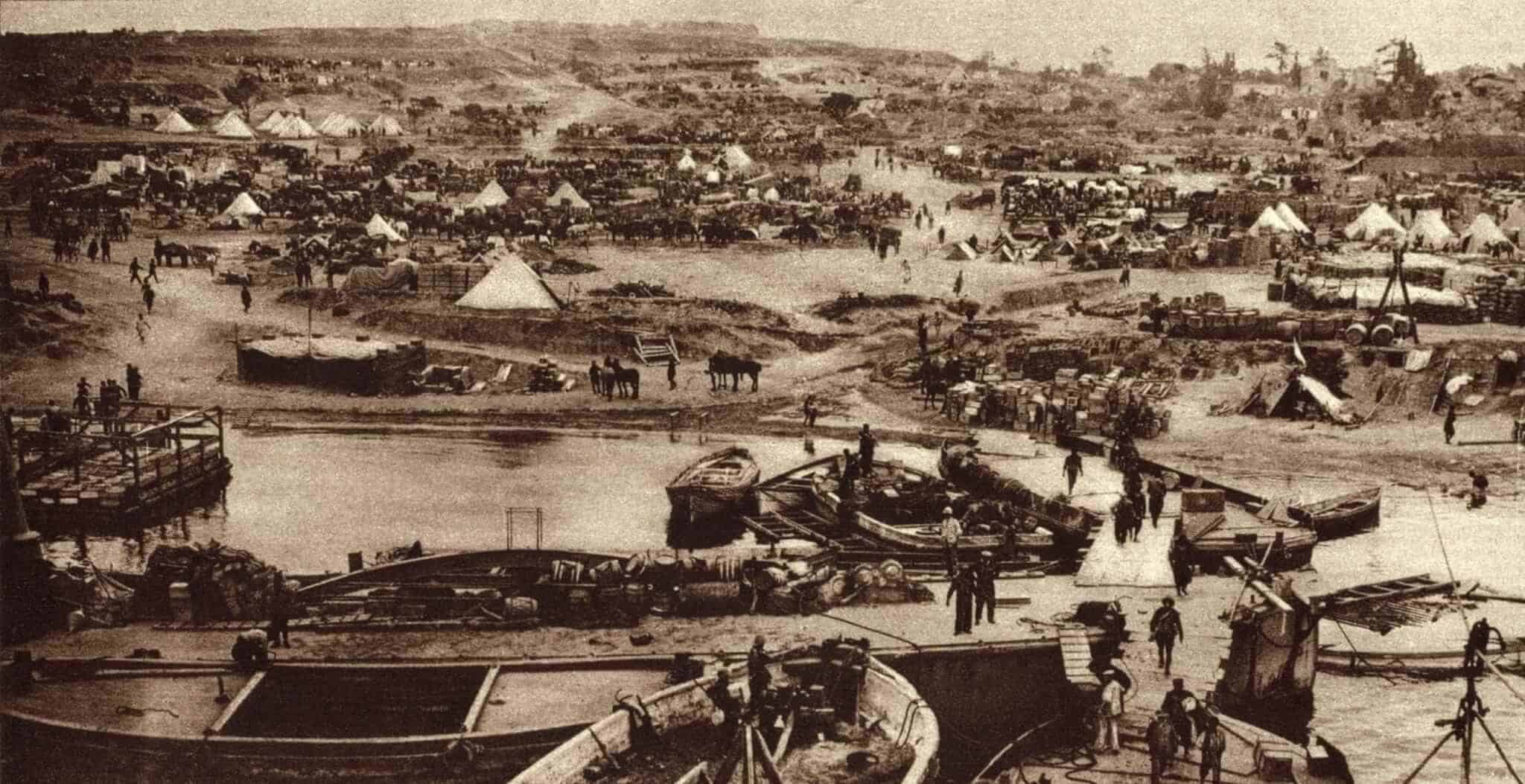

Born in Scarborough in 1868, Ronald had a fairly standard lower upper-class upbringing before joining the Green Howards Regiment in 1887. Ronald saw service in Egypt, Cyprus and India before moving to Bhamo in what was then known as Burma (Myanmar). It was there that he first took note of local idiosyncrasies, in this case the penchant for opium.

“One day I tried smoking opium to see what the effect would be. As instructed, I lay on the floor, my head being supported by a high and very hard pillow. An attendant then knelt by my side with a small lighted lamp and a pot containing the opium which resembles dark coloured and very thick treacle. The pipe with a long bamboo stem and large porcelain bowl was handed to me. It had a small orifice at the top. Taking what looked like a skewer the attendant dipped it in the pot and twirled it round until a large bead of opium was on the end. He then held this over the lamp until it fizzled, when he plastered it on to the opening of the pipe. Less than half a dozen pulls exhausted the supply, and another lot was then prepared. After two or three pipes I gave it up, as it produced no sensation whatever, and the visions for which I was hoping did not materialise.” – Mosaic of memories. Lt.-Col. Ronald Fife, C.M.G, D.S.O. Heath Cranston Ltd. 1943

From Burma he sailed home on leave on the same Troopship as the 4th Hussars where he made the acquaintance of a young Winston Churchill.

“In spite of his youth, his dominating personality had already begun to assert itself, and he had great influence with his brother officers. I was much struck by his vitality and clear incisive method of expressing himself, also by his studious habits. I remember that, when all around him were amusing themselves on deck, he could be seen sitting in a corner, reading Gibbon’s Decline and Fall.” – Mosaic of memories

Ronald saw action against Afridi tribesmen in 1897, being slightly wounded at the Arhanga Pass. Again, his eye for a tale was piqued.

“Near our camp there were the shrine and tomb of a holy man…..some years ago he had preached to the Afridis telling them that they had led wicked lives, and to atone for their sins it was necessary that they should pilgrimage to Mecca. On explaining where Mecca was and the length of the journey necessary to go there, they deliberated and at last decided that, as the prophet’s tomb was far away, it would be better to have a holy place nearer home. They then cut the throat of the preacher and gave him a handsome funeral and a nice tomb. Around which they planted a grove of walnut trees. This practical solution of the religious problem seemed to have solved all their difficulties.” – Mosaic of memories

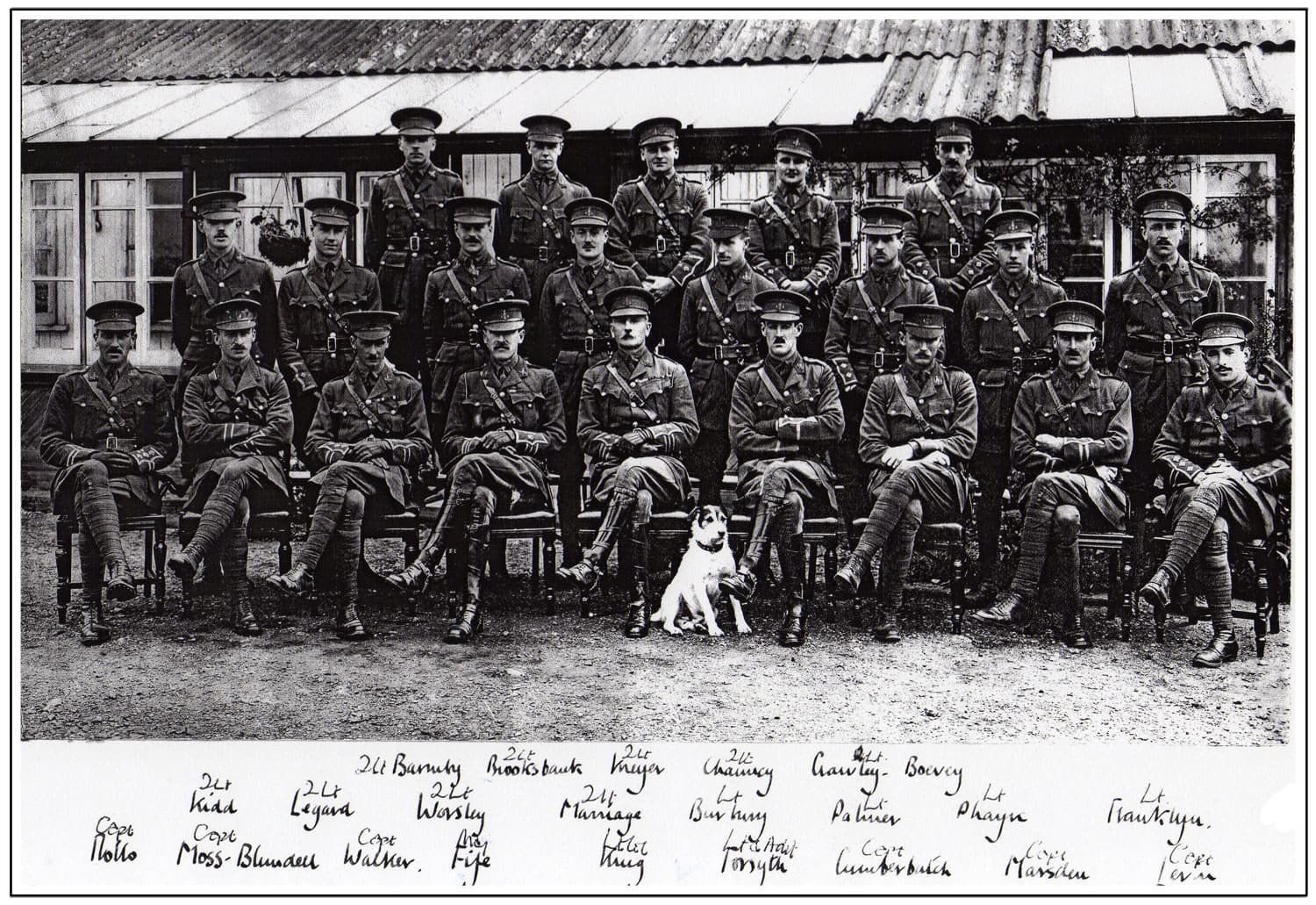

In the spring of 1913, Ronald met Margaret Rushton at a weekend shooting party in Cheshire and, after three days, asked her to marry him. She accepted and promptly left for home, leaving Ronald to realise that he did not know her surname! Luckily the Visitor Book provided the answer he needed. Later that year Ronald retired from the army. When war came, he applied for and was given command of the new 7th Battalion of his old regiment, the Green Howards.

The Battalion did its training at Wareham in Dorset and the influx of numbers to the Colours had placed the Army Service Corps under serious pressure resulting, in the case of the 7th Battalion, in a lack of even the most basic supplies. For Ronald the solution was simple, he went into the bank at Wareham, cashed a cheque on his own account and proceeded to buy every knife, fork, spoon, plate and bale of hay available in the town.

Ronald and the 7th Battalion sailed to France on 13th July 1915 and moved up to the Ypres Salient. Their experience is as tragic and sad as any soldier in the Great War, but what is clear is the extent to which Ronald believed that his role was the antithesis of the contemporary view of a regimental officer and a Battalion commander at that. As a Lieutenant-Colonel he was a regular sight on his almost daily rounds of the front-line trenches and as a keen sportsman and not un-shabby shot, Ronald was ever on the lookout for places from which his marksmen might undertake some execution among those opposite, often partaking himself when the opportunity arose, regardless of any danger.

Having a Battalion commander who was willing to share both their miserable conditions and the peril of the trenches did much to endear Ronald to the rank and file. Sadly, for Fife, tales of his sniping sorties got through to higher command and he was ordered by Divisional command to do no more as COs “…are scarce”.

Ronald survived frontline life until 14th February 1917 when he was wounded by shellfire at Sailly-Saillisel. He never returned to front line duty, but left a lasting mark on his men:

“A great sports man, a good horseman, an excellent shot and skilled fisherman. Endowed with good looks and health, he was completely self-assured. He was a great gentleman, but inclined to be intolerant of those less well born. To him the human race was clearly divided between those of who he approved, and the others. His sarcasm about those whom he disliked could be, and often was, devastating. Peace time soldiering did not interest him, although he carried out his duties efficiently.

And yet he proved himself to be a splendid CO of the 7th Bn in the 14-18 war. The filth and squalor of the Somme and the Ypres Salient left him quite unperturbed; he found no difficulty in rising above such conditions. He ignored danger and could be seen taking an afternoon walk down the Menin Road, the most awe-inspiring place on the whole front. It was most disconcerting when creeping along a ditch beside the road to meet Ronald Fife swinging his stick and strolling down the middle. He satisfied his sporting instincts by sniping at the Germans from insecure hiding places till this was forbidden him. He was intensely proud of his Bn and the Bn was proud of him. He took infinite pains to look after his men and to give them the best chances in operation, many of which were deplorably planned from above. He treated the war and his superiors with disdain: perhaps the war rather more so. Outwardly he appeared cold and almost inhuman, and yet he could be and was a warm-hearted and loyal friend.” – Green Howards Museum. M316

During the Second World War Ronald enlisted as a private in his local Home Guard unit, where his Gamekeeper was his Platoon Sergeant! He died on 17th November 1946. A more untypical ‘Donkey’ cannot be imagined.

Steve Erskine is a researcher at The Green Howards Museum in Richmond, North Yorkshire where you can learn more about the famous regiment, from its creation in 1688 to its amalgamation in 2006. Highlights of the Collection include Napoleon’s snuff box, taken on the field of Waterloo, a section of Hitler’s desk and the carpet from his office and fourteen Victoria Crosses, including the only one awarded at the D-Day landings.