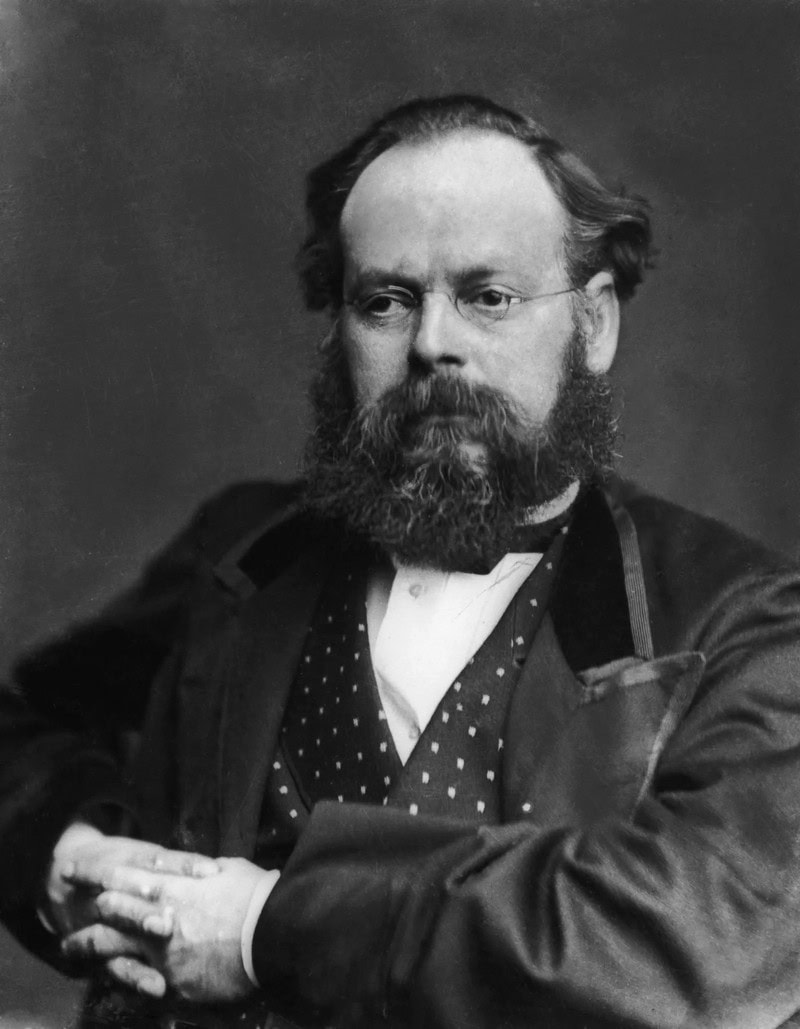

“The state of things I shall herein try to make plain is only of recent growth; but it involves such cruelty to animals, and so much loss of life to seamen, that I should have given it precedence … ” wrote a campaigner against live animal shipping. The words express a remarkably contemporary sentiment, but they are not of recent date. They are those of philanthropist and inventor Samuel Plimsoll (1824-1898).

Plimsoll was one of the leading campaigners and philanthropists of the Victorian age. This year, 2024, marks the bicentenary of his birth, in February 1824 to be precise. Born in Bristol, he subsequently lived in Penrith and Sheffield in his youth. As with so many individuals of that time, coal and the sea played an important part in his personal history and finances, as well as that of his family.

His father Thomas was an excise man, and his both his paternal and maternal grandfathers had connection to sea trade, the former as a chandler and the latter as a shipwright. Samuel was one of a family of thirteen, not all of whom survived to adulthood. Coming from a dissenting church background, Samuel was conscious from an early age of life’s inequalities and injustices.

While still a boy, he wrote ‘A Plan to Have Fatherless and Motherless Children Cared For Instead of Being Consigned to the Work-house’. His family had personal experience of poverty, particularly after his father died, and Samuel committed himself at an early age to the cause of improving the lives of impoverished people.

Looking after his mother and his younger siblings from the age of sixteen, Samuel was well aware of the difficulties of living on limited means. As well as his commitment to social welfare, Samuel developed an entrepreneurial side to his character. He needed to, with so many people to support. Later this would prove to his great benefit, and that of other people, in patenting several useful inventions. He realised that education was one way out of poverty, and despite his responsibilities, he dedicated time to study. Eventually he found decently-paid employment as a clerk and made something extra through speech-writing for local dignitaries in Sheffield.

Plimsoll was naturally drawn to the Liberal party. He found employment in London at the time of the Great Exhibition, promoting Sheffield’s products. While his name would later become best-known for his work on improving the safety of shipping, it was the cause of coal miners that first drew his attention to the need for improved safety for working people, and the devastating effect the death and injury of miners had on the families they left behind. He was active not only in promoting this cause but also in personally designing innovative ideas to improve safety in mining. As Plimsoll’s biographer Nicolette Jones writes: “Throughout his career Plimsoll demonstrated that he was also at heart an inventor, as was his brother Henry, who eventually held a dozen patents for pieces of industrial machinery”.

Samuel Plimsoll not only campaigned for safer working conditions, and devised useful technology to aid this, but also raised funds for mining families left bereaved after mining disasters at collieries in Yorkshire. His brother Thomas was manager of the Sunderland and Hartlepool Coal Company, and Samuel joined him in London in 1853. This was also the year in which his own business venture into coal and transportation came to grief, leaving Samuel Plimsoll bankrupt and briefly destitute.

Samuel had planned to transport coal from Yorkshire collieries by rail, rather than sea, as it had been carried for centuries. Coal had been mined and collected on beaches in North East England since medieval times, and increasing quantities of it were shipped to London by sea from Tudor times onward on vessels known as colliers. Samuel’s business project would have broken this long-time sea-going monopoly. A dangerous monopoly too, for the risks were high for those who engaged in it.

Bella Bathurst, author of “The Wreckers”, noted that Durham was “the county with by far the worst shipwreck record in the whole of the British Isles. The reasons for its appalling total of 43.8 wrecks per mile lie both in the geography of that coastline, and in its erstwhile economic identity as the home of shipbuilding, coal, and iron”. All these trades came at a high cost in human (and animal) lives and suffering.

Led on by two senior managers in the Great Northern Railway that now operated between Leeds and London, Samuel invested heavily in his idea. He was thwarted by his would-be colleagues, and in his early thirties, found himself bankrupt and briefly down-and-out in London. This would prove the making of Samuel Plimsoll, and also confirm his belief in the natural goodness of poor people and the need for those who were better-off and could provide assistance, to do so.

Life among the poor offered many opportunities for Samuel’s education in compassion. Importantly, he noted how much the poor cared for one another, a quality that was less visible among the money-making classes. Ironically, Samuel’s own church cast him out for speculating in hazardous business ventures, and, worst of all, for risking borrowed capital.

When in 1857 Samuel married Eliza Ann Railton, stepdaughter of a partner in a mining company. Her stepfather was able to help Samuel to further his plan for transporting coal from the Yorkshire collieries to London by train.

Samuel was a superb publicist, able at drawing the press to his cause, and very well aware of the grand gesture in influencing people. He was one of those people whom it’s not hard to imagine as a modern internet sensation. He identified closely with working-class people and had highly critical views on the wealthy, as his biographer Nicolette Jones reveals in this quote: “I don’t wish to disparage the rich, but I think it may be reasonably doubted whether these qualities [of honesty, strong aversion to idleness, tenderness to one another in adversity and courage] are so fully developed in them”.

Samuel had another opportunity to experience these qualities and to empathise with them, after a stormy sea voyage from London to Redcar (on the north Yorkshire coast) in 1863. Samuel’s ship survived and made it to port, but several other vessels did not. The rejoicing of Samuel and his wife at his survival was sobered by the presence of the widows and children of the unfortunates who had drowned in shipwrecks so close to home.

The truth was that commercial shipping, in which Britain’s coastal and international trade played so significant a part, was riddled with corruption. Ships were overladen, were ill-maintained and still in service when they should long since have been scrapped. Several notorious shipwrecks had brought a public outcry, especially when the reprehensible activities of ship owners were brought to light. The wreck of the Birkenhead, for instance, which is said to be the origin of the phrase “women and children first”, since the women and children were placed into the lifeboat first, had been caused by cutting open the watertight bulkholds to create better accommodation below deck. Many of the crew and soldiers on board died as a result. The Birkenhead was a troopship and not a commercial vessel, but the same cost-cutting and lack of attention to safety applied to commercial vessels. Insurance fraud was also rife, but no one moved to prevent it.

Samuel’s political career began in the 1860s. In 1868 he was elected to Parliament as a Liberal MP. After engaging with various causes, including animal welfare, he took up the cause of seamen in 1870. One suggestion that had already been made was that there should be some way of marking on the side of a ship the maximum level to which it should be loaded, but nothing had been done to institute this.

An encounter between Samuel and an equally entrepreneurial and philanthropic character, James Hall, a shipowner from Newcastle upon Tyne, was to lead to the visibility of this important principle and increased awareness in press and public. Hall set up petitions to make it a reality. Reform was in the air. Colliers, the ships carrying the coal, were some of the most at-risk vessels, frequently overloaded. and the loss of life was terrible.

Samuel Plimsoll’s first bill relating to shipping was presented in 1871. The two principles of the bill were that all vessels should have a safe load line; and that all vessels should be regularly inspected. It failed at its second reading. Samuel then wrote a book entitled “Our Seamen: An Appeal”. No one benefitted, Samuel argued passionately, from cutting corners and underinvesting, taking terrible risks in order to advance profits. There was even a term for the ships that were doomed to disaster: Coffin Ships.

Samuel’s impassioned, if idiosyncratic, writing caught the notice of the press. He wasn’t afraid of naming and shaming those shipowners who sent out overloaded ships in dangerous conditions, and his habit of engaging with them directly inevitably led to litigation. In the meantime, he was gaining supporters – and also some enemies – in the House of Commons. However, Samuel was never afraid to stand up for what he believed in, even on the floor of the House of Commons, which resulted in him having to issue apologies occasionally.

On the 10th-11th 1873 February the House of Commons Journal reported “That the Chairman be directed to move the House, That leave be given to bring in a Bill to provide for the Survey of certain Shipping, and to prevent overloading … That leave be given to bring in the Bill: And that Mr. Plimsoll, Mr. Horsman, Mr. Charles Lewis, Mr. Staveley Hill, Mr. Samuda, Mr Henry Carter, Sir Henry Selwin-Ibbetson, Sir Robert Torrens, Mr. Eykyn, and Mr. Villiers do prepare, and bring it in”.

Samuel Plimsoll himself duly presented the bill, which was ordered to be read a second time “upon Wednesday the 26th day of March next; and to be printed”. It appears this bill did not get its second reading until May. The subsequent 1873 Merchant Shipping Act did give the authorities the right to examine ships if they looked unseaworthy, but no more. Progress on reform was slow and often delayed by powerful vested interests. Samuel toured the country, talking to miners and other working people.

A Royal Commission was set up to investigate conditions and the potential for reform. In 1875 Samuel’s own bill was dropped, and Samuel blamed powerful forces in government, many of whom had a vested interest in shipping. His response was dramatic and loud, naming the members of parliament as villains, and shaking his fist at them, for which he later had to apologise. Samuel Plimsoll continued to campaign, protest and attend meetings. Public and press followed him avidly. The plight of Britain’s seamen was recorded in songs, poems, and stories. Punch was a particular supporter of Samuel at this stage, and its satirical cartoons, targeting Disraeli, Gladstone, and other senior political figures, provided additional fuel for the campaign. There was further recognition for Samuel. In 1873, an iron-hulled sailing vessel known as the Samuel Plimsoll was launched in Aberdeen as part of the White Star Line.

Disraeli was clearly rattled by “The Plimsollites, in and out of Parliament”, as he called them. From being a cranky cause that politicians had believed they could sweep aside, the campaign for safer shipping, and its focus on a safe loading line on the side of ships, had taken the nation by storm. Samuel Plimsoll was empathetic and emotional, and often unable to keep his feelings under control on the floor of the House of Commons. He inevitably drew accusations of insanity, to which one of his followers responded: “If Mr Plimsoll is mad, the sooner he bit a few other MPs the better.” He was also decried as “not a gentleman”.

One Conservative politician became the particular focus for Plimsoll’s attacks – the ship-owning Edward Bates, MP for Plymouth. The pair found themselves facing up to one another on various committees. One of Bates’s ships, a collier, was lost and subsequently the focus of a famous, or infamous court case on the topic of whether cannibalism was legally acceptable for desperate and starving castaways as “a custom of the sea”.

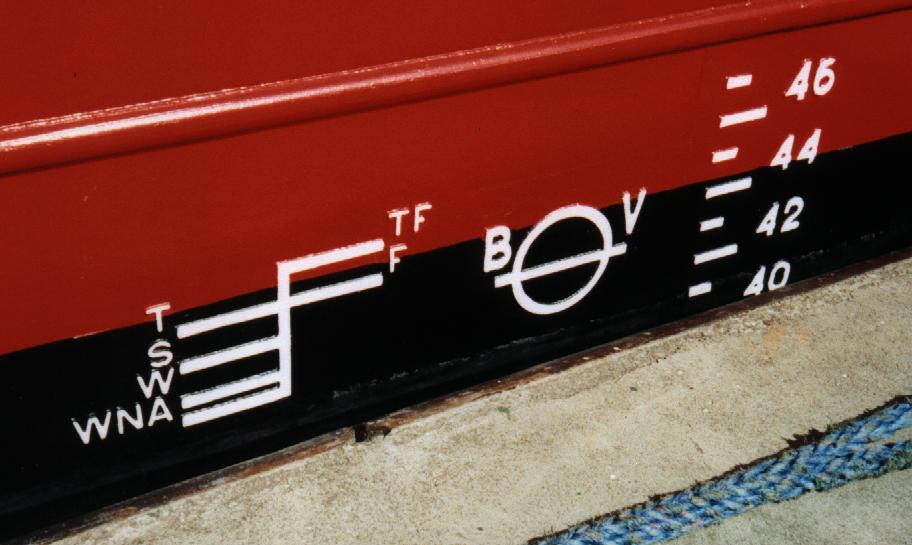

There is little doubt that it was Plimsoll’s tenacious attitude that finally brought about the 1876 Shipping Act, giving the Board of Trade the authority to inspect any merchant ships, which had to display a maximum loading line on them, now immortalised as the Plimsoll Line. The line was marked by a circle with a line through the middle. However, the enforcement of this line on shipping did not come until 1890; until then it was at the discretion of the shipowner.

The sobering statistic of 1,000 dead seamen in the previous year no doubt had its part to play in the final outcome of the 1876 Act, but it was Samuel’s unfailing dedication to the cause, and the power of public pressure, that brought principle into practice. With 150 years of hindsight, it seems so obvious and necessary an innovation that it is scarcely credible that anyone should have opposed it.

Samuel was made honorary president of the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union in 1887. He was a campaigner to the end. He now turned his attention to the terrible conditions suffered by shipping live animals such as cattle. Fittingly in the bicentenary of his birth, on 20th May 2024 the UK government placed a total ban on the export of all live animals from the UK.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 14th June 2024