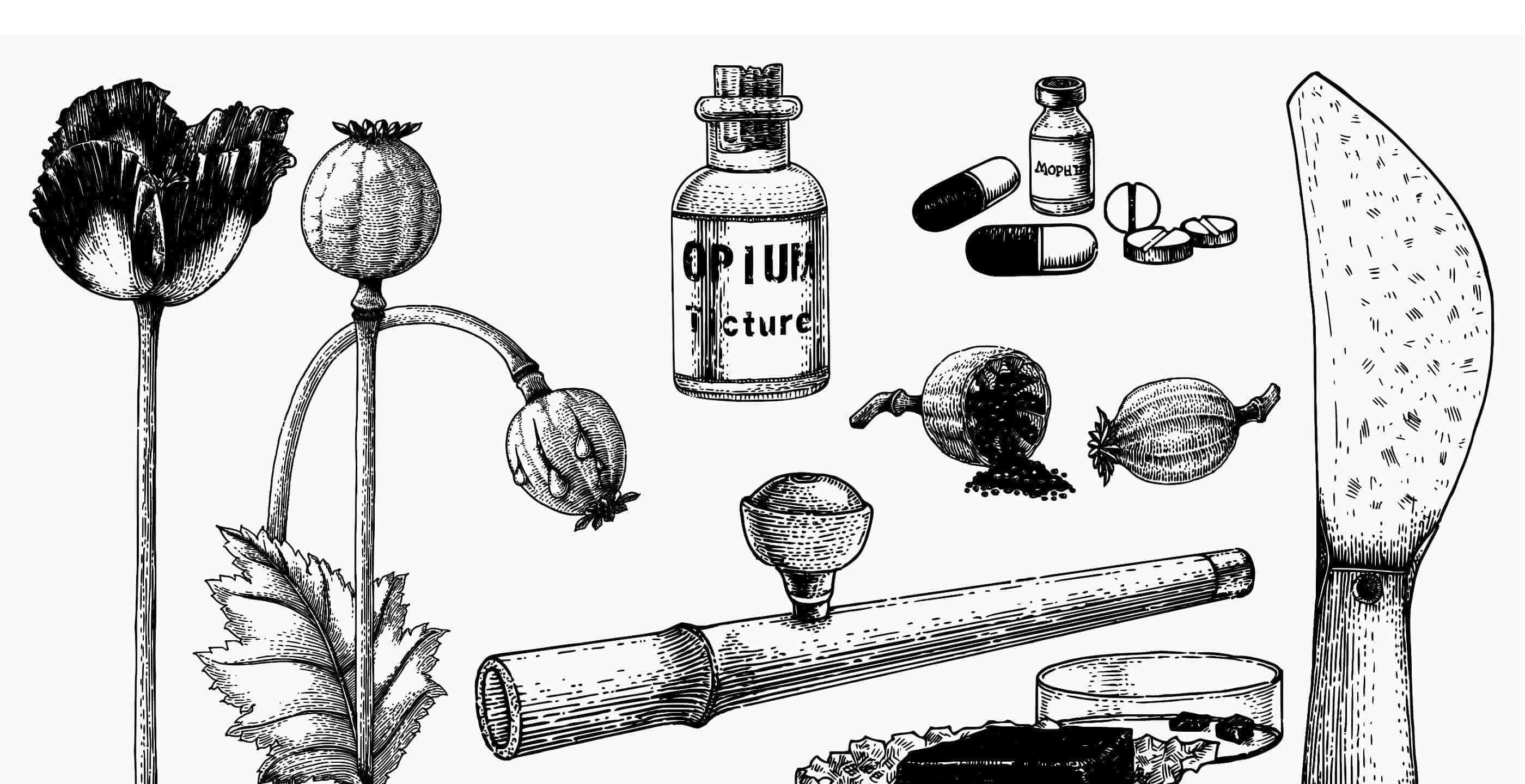

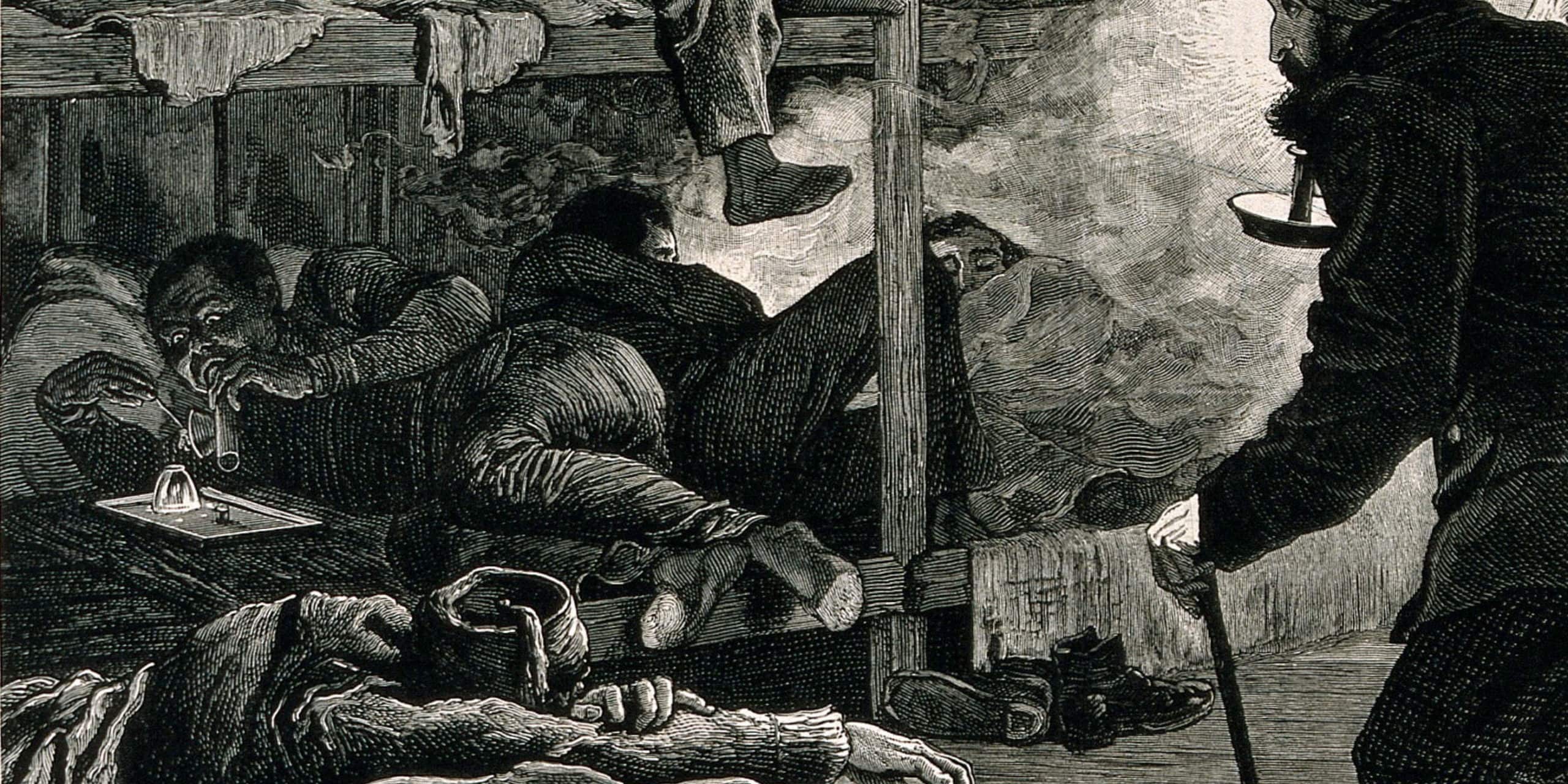

By 1856, largely thanks to the influence of Britain, ‘chasing the dragon’ was widespread throughout China. The term was originally coined in Cantonese in Hong Kong, and referred to the practice of inhaling opium by chasing the smoke with an opium pipe. Although by this point, the first opium war was officially over, many of the original problems remained.

Britain and China were both still dissatisfied with the unequal Treaty of Nanking and the uneasy peace that had ensued. Britain still desired that the trade of opium be legalised, and China remained deeply resentful of the concessions that they had already made to Britain and the fact that the British were continuing to sell opium illegally to their population. The question of opium remained worryingly unsettled. Britain also wanted access into the walled city of Guangzhou, another massive point of contention at this time as the interior of China was prohibited to foreigners.

To further complicate matters, China was embroiled in the Taiping Rebellion, starting in 1850 and creating a period of radical political and religious upheaval. It was a bitter conflict within China that took an estimated 20 million lives before it finally came to an end in 1864. So as well as the issue of opium continually being sold illegally in China by the British, the Emperor also had to quell a Christian rebellion. However, this rebellion was heavily anti-opium which complicated things further, as the anti-opium stance was beneficial to the Emperor and the Qing dynasty. However it was a Christian rebellion and China at this time practiced Confucism. So although there were parts of the rebellion that were widely supported, including their opposition to prostitution, opium and alcohol, it was not universally supported, as it still contradicted some deeply held Chinese traditions and values. The Qing dynasty’s hold on the region was becoming more and more tenuous, and the open challenges to their authority by the British were only fuelling the fire. Tensions began to escalate between the two great powers once again.

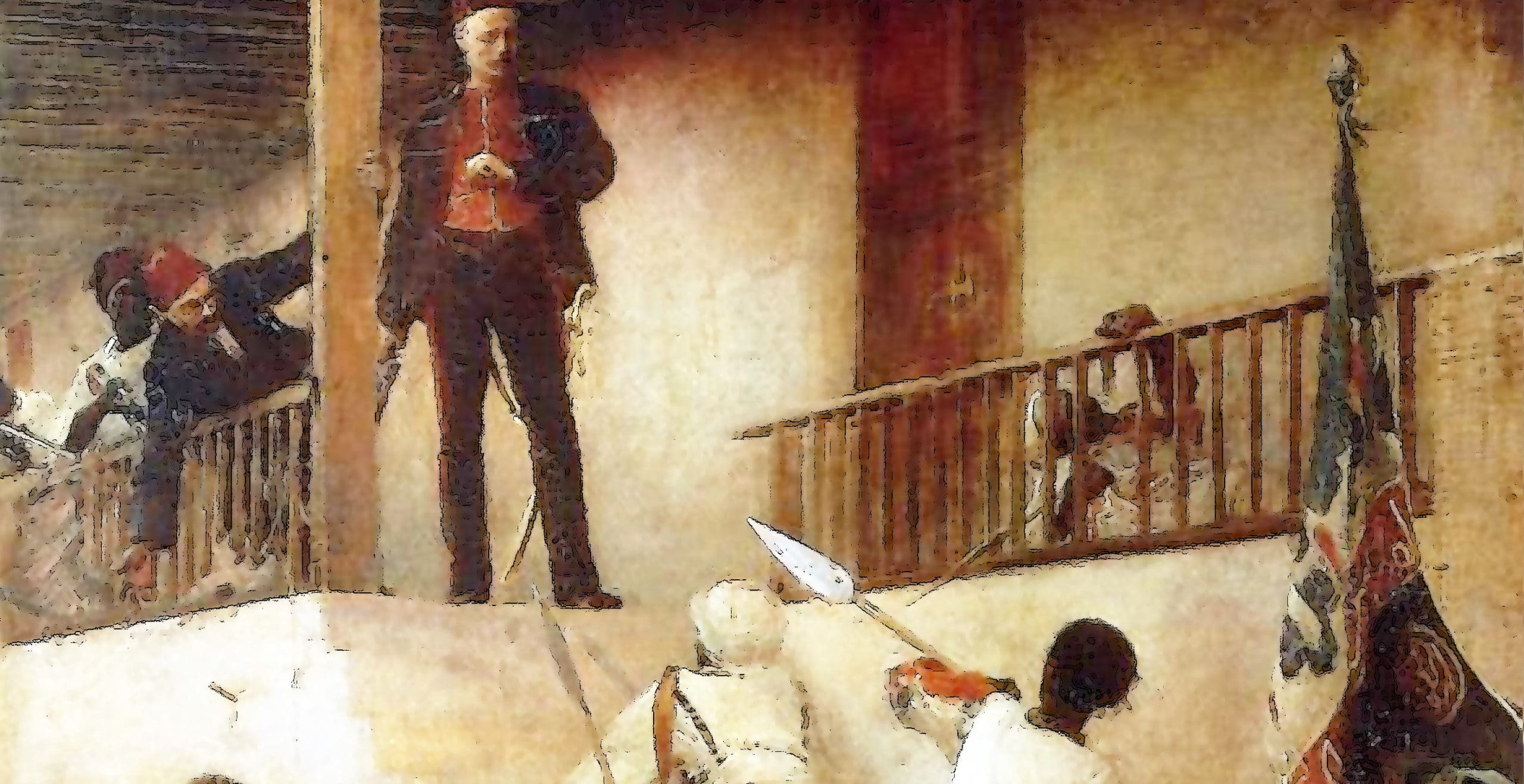

These tensions came to a head in October 1856, when the British registered trading ship the ‘Arrow’ docked in Canton and was boarded by a group of Chinese officials. They allegedly searched the ship, lowered the British flag and then arrested some of the Chinese sailors on board. Although the sailors were later released, this was the catalyst for a British military retaliation and skirmishes broke out between the two forces once again. As things escalated, Britain sent a warship along the Pearl River which began firing on Canton. The British then captured and imprisoned the governor who consequently died in the British colony of India. Trading between Britain and China then abruptly ceased as an impasse was reached.

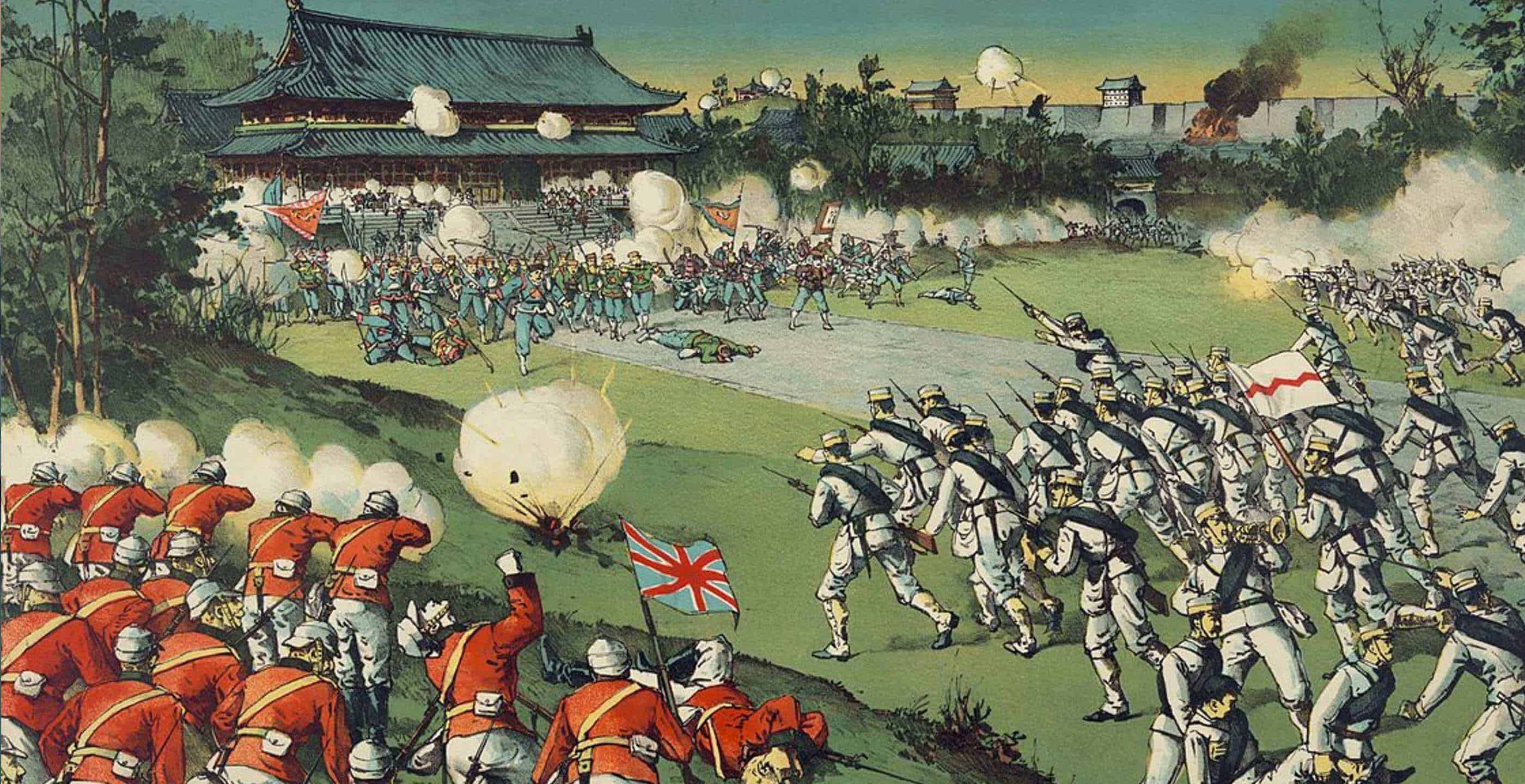

It was at this point that other powers began to get involved. The French decided to become embroiled in the conflict as well. The French had a strained relationship with the Chinese after a French missionary had allegedly been murdered in the interior of China in early 1856. This gave the French the excuse they had been waiting for to side with the British, which they duly did. Following this, the USA and Russia also got involved and also demanded trade rights and concessions from China. In 1857 Britain stepped up the invasion of China; having already captured Canton, they headed to Tianjin. By April 1858 they had arrived and it was at this point that a treaty was once again proposed. This would be another of the Unequal Treaties, but this treaty would attempt to do what the British had been fighting for all along, that is, it would officially legalise the import of opium. The treaty had other advantages for the supposed allies as well however, including opening new trading ports and allowing the free movement of missionaries. However, the Chinese refused to ratify this treaty, somewhat unsurprisingly, as for the Chinese this treaty was even more unequal than the last one.

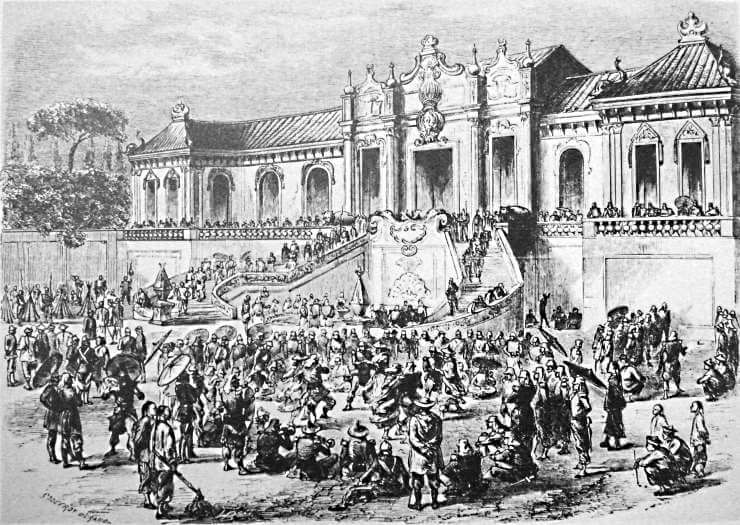

The British response to this was swift. Beijing was captured and the Imperial summer palace burned and pillaged before the British fleet sailed up the coast, virtually holding China to ransom in order to ratify the treaty. Finally, in 1860 China capitulated to the superior British military strength and the Beijing Agreement was reached. This newly ratified treaty was the culmination of the two Opium Wars. The British succeeded in gaining the opium trade that they had fought so hard for. The Chinese had lost: the Beijing Agreement opened Chinese ports to trade, allowed foreign ships down the Yangtze, the free movement of foreign missionaries within China and most importantly, allowed the legal trade of British opium within China. This was a huge blow to the Emperor and to the Chinese people. The human cost of the Chinese addiction to opium should not be underestimated.

However these concessions were more than just a threat to the moral, traditional and cultural values of China at the time. They contributed to the eventual downfall of the Qing dynasty in China. Imperial rule had fallen to the British time and time again during these conflicts, with the Chinese forced into concession after concession. They were shown as no match for the British navy or negotiators. Britain was now legally and openly selling opium within China and the trade of opium would keep increasing for years to come.

However, as things changed and the popularity of opium decreased, so did its influence within the country. In 1907 China signed the 10 Year Agreement with India by which India promised to stop cultivating and exporting opium within the next ten years. By 1917 the trade had all but ceased. Other drugs had become more fashionable and easier to produce, and the time of opium and the historic ‘opium eater’ had come to an end.

Ultimately it took two wars, countless conflicts, treaties, negotiations and no doubt a substantial number of addictions, to force opium into China – just so that the British could enjoy their quintessential cup of tea!

By Ms. Terry Stewart, Freelance Writer.