“Quite enough disaster for today.” In an anecdote somewhat buried in his Memoirs of the Second World War, Prime Minister Winston Churchill recounts a “frightful incident” that occurred on June 17, 1940.

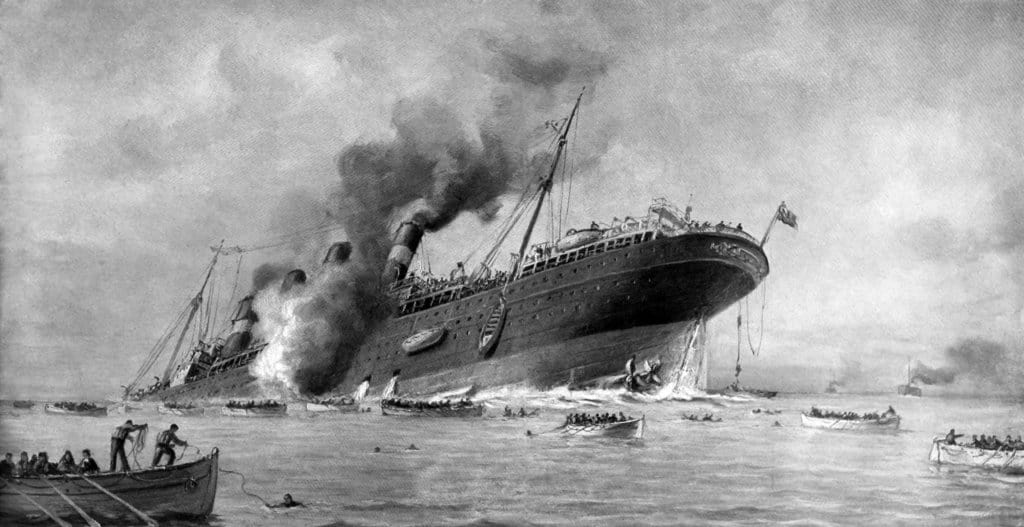

“The 20,000-ton liner Lancastria, with five thousand men aboard, was bombed just as she was about to leave. Upwards of three thousand men perished. The rest were rescued under continued air attack by the devotion of the small craft.”

The British government had requisitioned the Cunard ocean liner to continue bringing British Expeditionary Force troops back to Britain following the evacuation of Dunkirk.

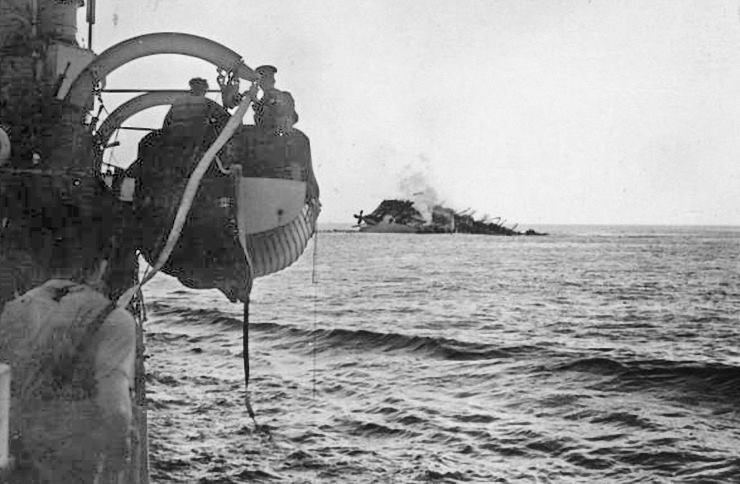

The ship’s captain was instructed to take on as many passengers as possible, so estimates for the number of souls aboard on June 17 range between 5,000 and 7,000. This number far exceeded the amount of life jackets and lifeboats onboard, but this lack of safety equipment ultimately did not matter. The liner sank within 20 minutes of being bombed by the Luftwaffe. Approximately four thousand men, women, and children were buried beneath the waves. As were news reports on the sinking. “When this news came to me in the quiet Cabinet Room during the afternoon,” continued Churchill, “I forbade its publication, saying ‘The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for today at least.’”

A few eyewitnesses told of soldiers balancing on the upturned hull and singing “Roll out the Barrel” as the ship listed to port. Others told of retrieving the corpses that washed up on the beaches a few days later. Eyewitness Emile Boutin (whose stories are included in the online Lancastria archive) wrote, “Sometimes one body arrived, sometimes 16 arrived at once… other times there were four days, five days without anything.” The citizens of Moutiers buried the victims behind a sea dike, where “they stayed…until the end of the war. Moutiers people never talk, never talked about the Lancastria, but about the cemetery of the British.” It was not until 2006 that the French government afforded the site official legal protection as a war grave.

The French had a front row seat to the destruction, but the British people were kept in the dark. Churchill’s D-Notice asked all media outlets not to publish any information on the Lancastria sinking. It was not an official government order, but the British media followed Churchill’s lead. American and Scottish newspapers did print the story, but not until the end of July. Churchill even admitted he forgot to lift the D-Notice because “events crowded upon us so black and so quickly.” That D-Notice is not set to expire for another twenty years.

Though more people died on the Lancastria than on Titanic and Lusitania combined, the story is little more than a footnote in the history of WWII. German bombing raids shifted the focus away from the sea and onto the mainland, and the nation’s attention also shifted to fresh challenges and atrocities. Official commemorations of those lost during the disaster were long in coming. Almost 50 years later, a memorial was erected in St. Nazaire, reading:

“Opposite this place lies the wreck of the troopship Lancastria sunk by enemy action on 17 June 1940 whilst embarking British troops and civilians during the evacuation of France. To the glory of God, in proud memory of more than 4,000 who died and in commemoration of the people of Saint Nazaire and surrounding districts who saved many lives, tended wounded and gave a Christian burial to victims. We have not forgotten. HMT ‘Lancastria’ Association, 17 June 1988.”

Lancastria survivor Charles Napier with a copy of the newspaper which reported the news of the Lancastria sinking. Mr Napier is also wearing the Lancastria commemorative medal which was awarded by the Scottish Government in June 2008 in recognition of those who were aboard the vessel that day.

Lancastria survivor Charles Napier with a copy of the newspaper which reported the news of the Lancastria sinking. Mr Napier is also wearing the Lancastria commemorative medal which was awarded by the Scottish Government in June 2008 in recognition of those who were aboard the vessel that day.

In 2011, a memorial was dedicated in Clydesdale, Scotland, where the ship was built. Memorials in statue, plaques, and stained glass can be found in Staffordshire, Liverpool, and London. Though buried in WWII history, the sinking of the Lancastria reminds us of the sacrifices and loss of thousands of men, women, and children during the war. Their names may be lost to history, but they are not forgotten.

Kate Murphy Schaefer is an undergraduate history instructor who studies the human impact of wars and revolutions.

Published: 26th November 2020.