An invention that changed the world was 200 years old in 2004. Britain celebrated the bicentenary of the steam railway locomotive with a year-long events programme, but it was not an engineering giant such as James Watt or George Stephenson that was fêted.

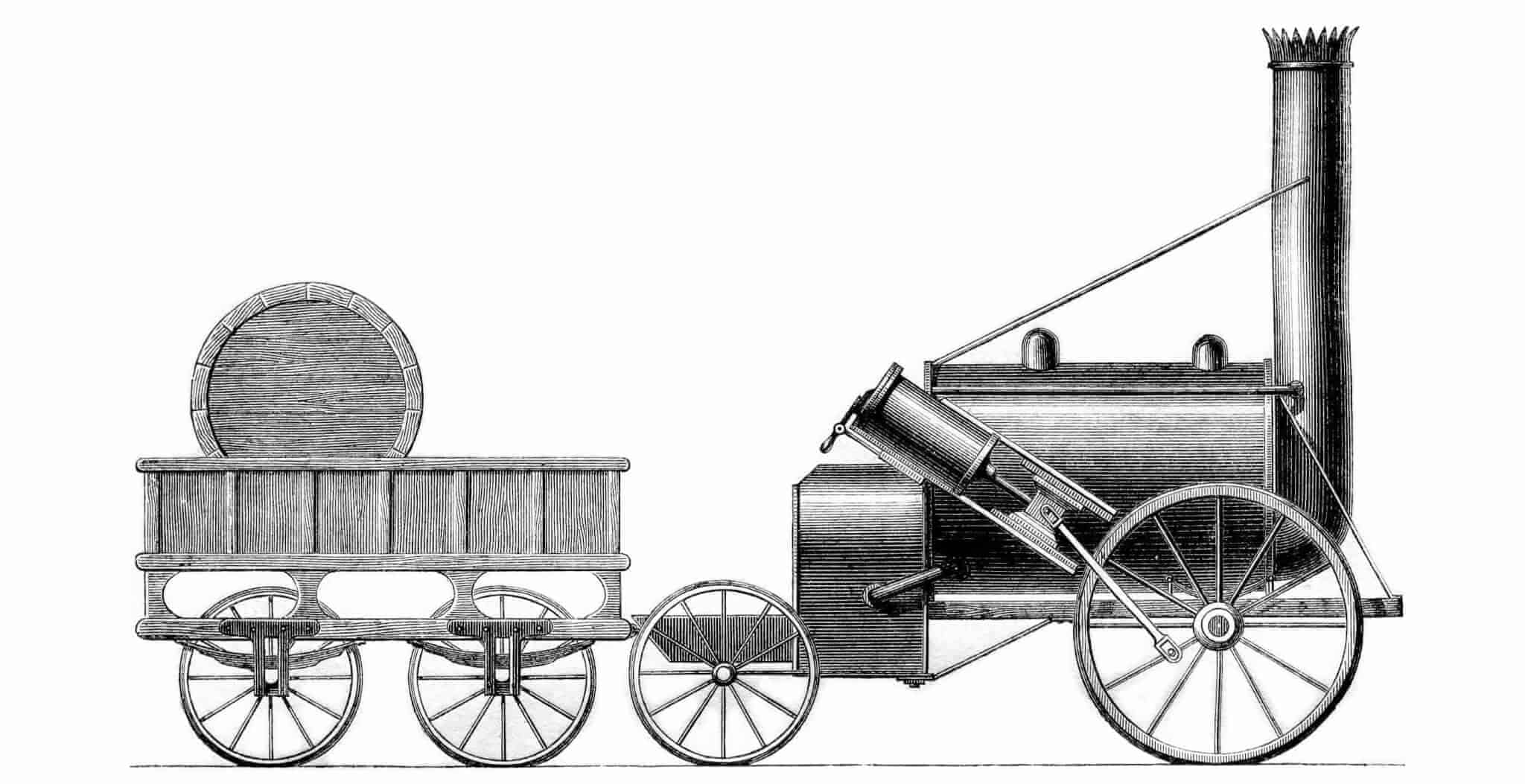

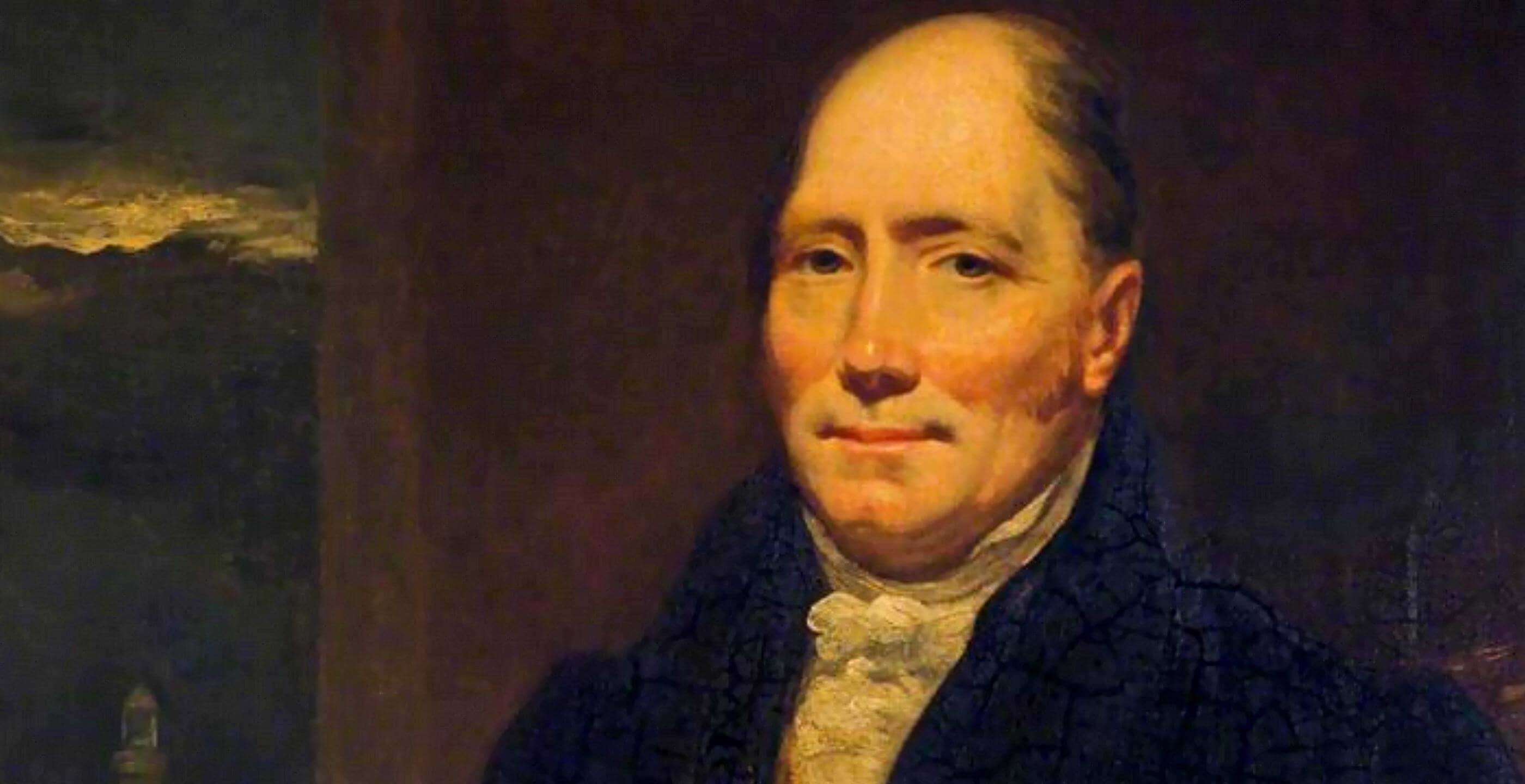

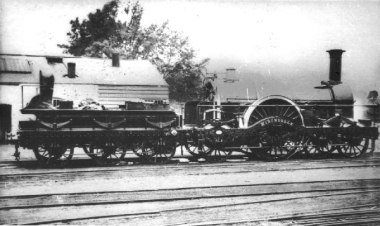

The man who first put steam engines on rails was a tall, strong Cornishman described by his schoolmaster as “obstinate and inattentive”. Richard Trevithick (1771-1833), who learnt his craft in Cornish tin mines, built his “Penydarren tram road engine” for a line in South Wales whose primitive wagons were pulled, slowly and laboriously, by horses.

On February 21, 1804, Trevithick’s pioneering engine hauled 10 tons of iron and 70 men nearly ten miles from Penydarren, at a speed of five miles-per-hour, winning the railway’s owner a 500 guinea bet into the bargain.

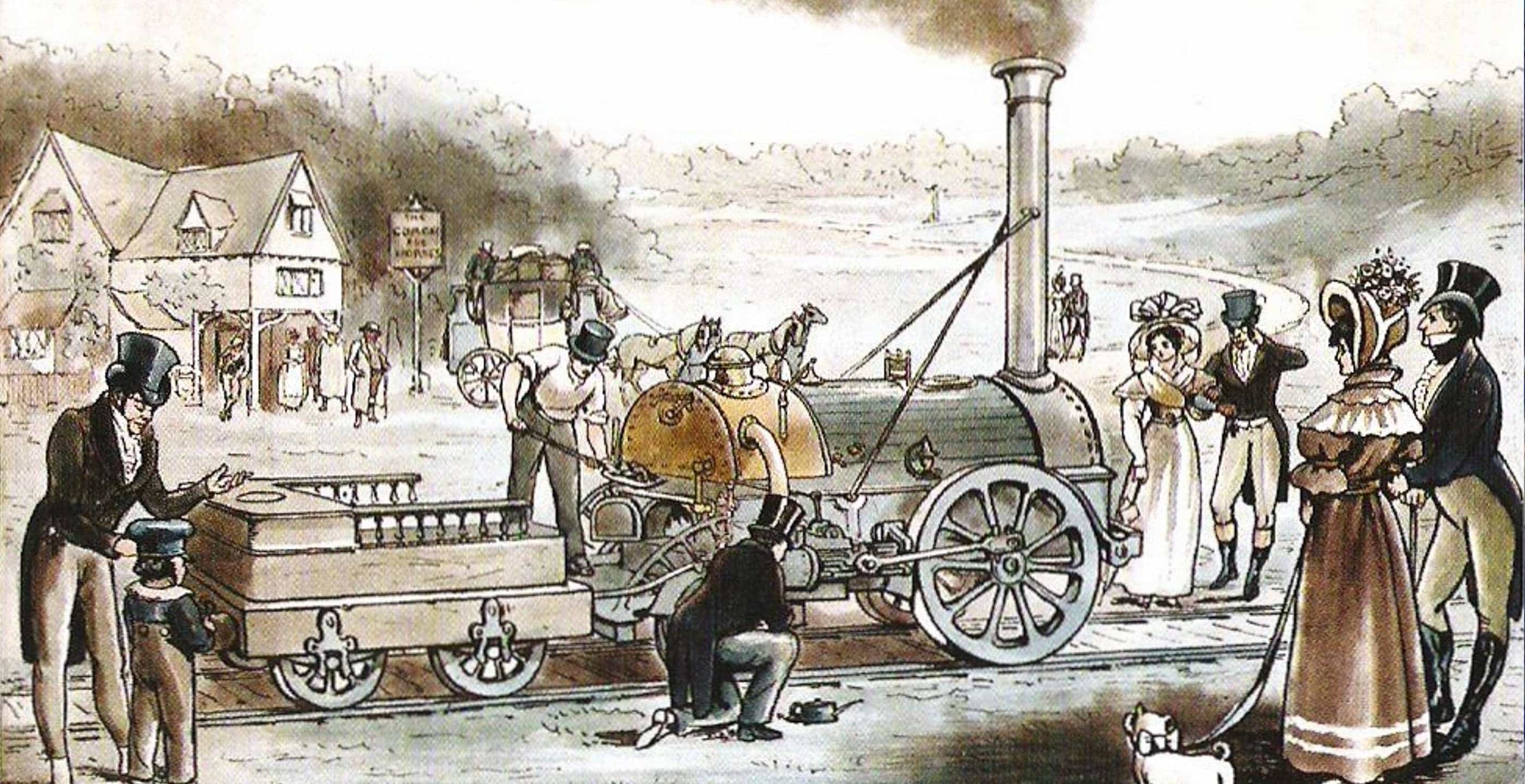

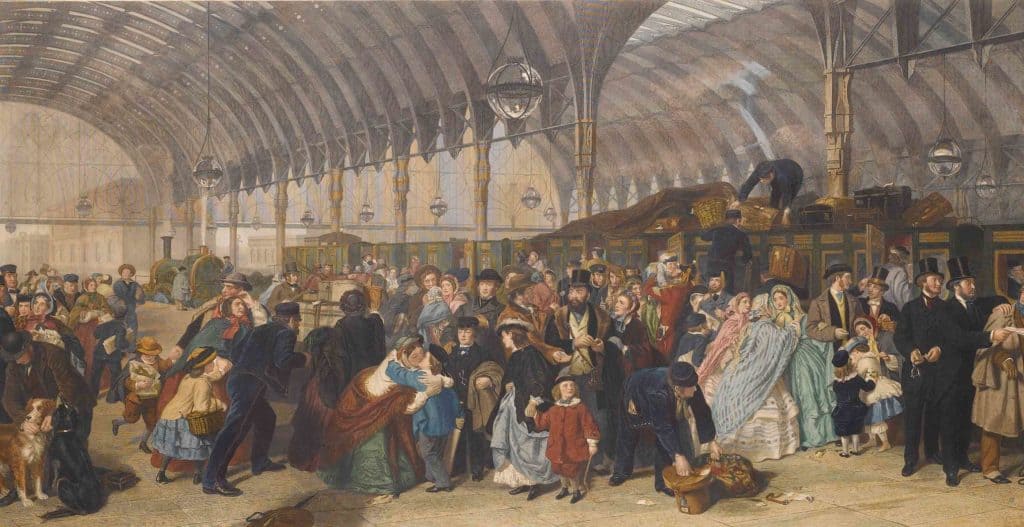

He was 20 years ahead of his time – Stephenson’s “Rocket” was not even on the drawing board but Trevithick’s engines were seen as little more than a novelty. He went on to engineer at mines in South America before dying penniless aged 62. But his idea was developed by others and, by 1845, a spider’s web of 2,440 miles of railway were open and 30 million passengers were being carried in Britain alone.

With the launch in January 2004 of a new £2 coin by the Royal Mint – bearing both his name and his ingenious invention, a coin approved by Queen Elizabeth II – Trevithick at last received the public recognition he deserved.

Perhaps because it was the birthplace, Britain can boast more railway attractions per square mile than any other country. The figures are impressive: more than 100 heritage railways and 60 steam museum centres are home to 700 operational engines, steamed-up by an army of 23,000 enthusiastic volunteers and offering everyone the chance to savour a bygone age by riding on a lovingly preserved train. The surroundings – stations, signal-boxes and wagons – are equally well preserved and much in demand by TV companies filming period dramas. (Website: https://www.heritagerailways.com)

Wales deserves a special mention for its Great Little Trains. Though small in stature, these narrow-gauge lines are real working railways, originally built to haul slate and other minerals out of the mountains, but now a wonderful way for visitors to admire the scenery, which is breathtaking. There are eight lines to choose from and one, the Ffestiniog Railway, is the oldest of its kind in the world.

Then there are the railway museums that are historic in their own right. “Steam” at Swindon is built into the former workshops of the Great Western Railway (GWR) which has near-legendary status among rail fans; the GWR Railway Centre at Didcot re-creates its golden age in an old steam depot where polished engines are tended lovingly. Part of Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry is situated in the world’s oldest passenger station; and the ‘Thinktank’ museum in Birmingham contains the world’s oldest active steam engine, designed by James Watt in 1778.

But it is North East England that is known as the birthplace of railways for here, around Newcastle, the world’s first tramways were laid and, later, the world’s first public railway between Stockton and Darlington steamed into life. At Shildon in County Durham, a £10 million permanent Railway Village is taking shape, to open in the autumn, the first out-station of the National Railway Museum.

At nearby Beamish, the open-air museum of North Country Life – where the past is brought magically to life – there’s an opportunity to see one of the earliest railways re-created. Feel the wind – and steam – in your hair as you travel in open carriages behind a working replica of a pioneering engine such as Stephenson’s Locomotion No.1, built in 1825.

If you can, go south-westwards to Cornwall where the story of the great engineer Trevithick began. In his home town of Camborne is a bronze statue of him holding a model of one of his engines; while not far away the little thatched cottage where he lived, at Penponds, is open to the public. It is hard to imagine that scribblings in this humble home were to lead to the ‘high-pressure steam engine’ and the world would never be quite the same again.

Published: 27th November 2014.