Delays, delivery mix-ups and leaking packages are just few of the problems that the bodysnatching profession were faced with on more than one occasion. It was one thing to dig up a cadaver in the local churchyard for delivery to a nearby anatomy school; it was something else entirely if you were trying to transport a body, perhaps across the full length of the country, while trying to avoid detection.

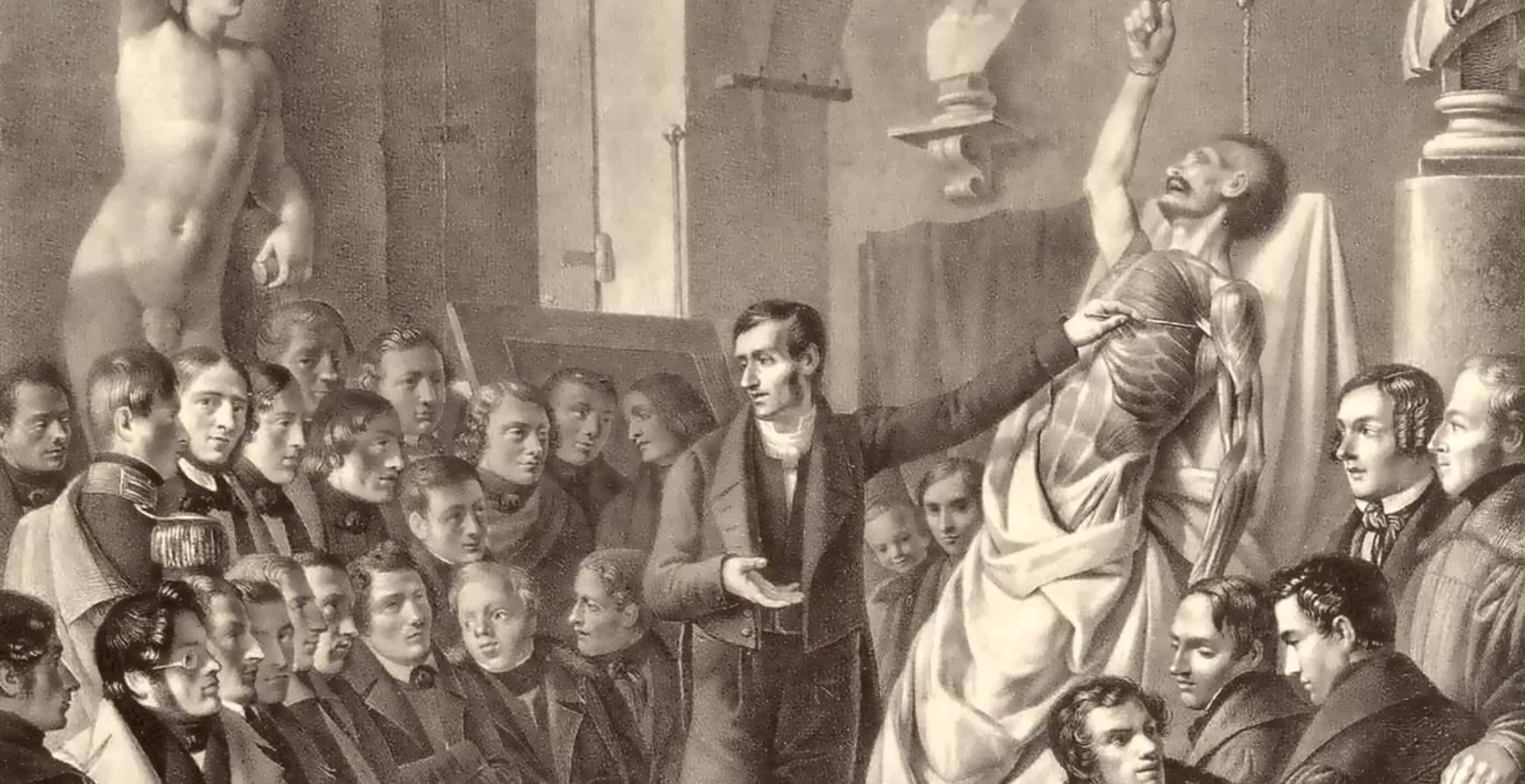

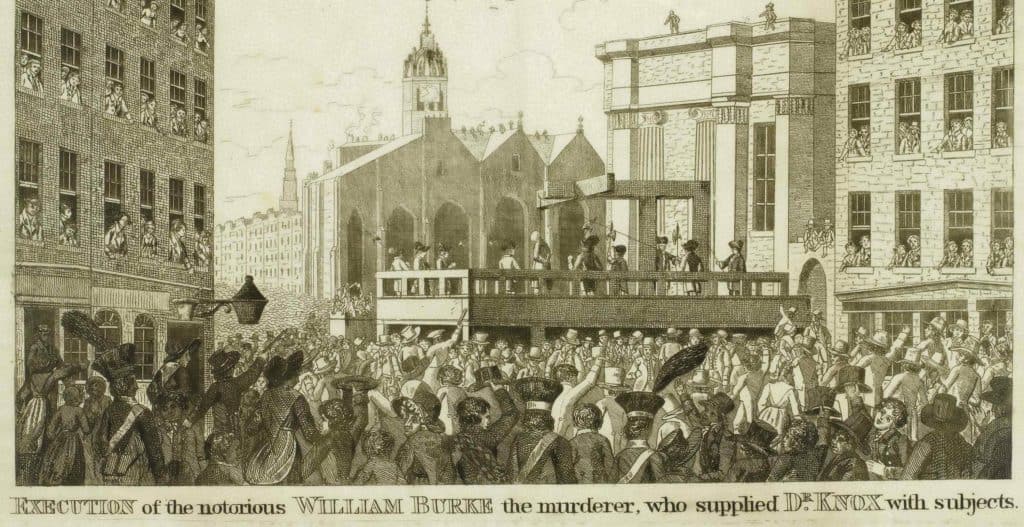

At the turn of the 19th century, the number of fresh cadavers legally available to the anatomy schools of England and Scotland was woefully inadequate. In order to address this shortfall, a new class of criminal emerged. The bodysnatcher or ‘Sack ‘em up men’ worked tirelessly up and down the length of Britain, raiding churchyards where any new burial had taken place. Cadavers were swiftly removed, stripped of their grave clothes and hastily bundled into waiting carts or hampers ready to be shipped to their final destination.

The Turf Hotel in Newcastle-upon-Tyne was a popular spot for discovery as it was a major stopping point on the route North or South. Nauseating smells would waft from the back of coaches destined for Edinburgh or Carlisle, or suspicious looking packages would demand closer inspection if perhaps a corner of the hamper in which the cadaver was being transported, was a little damp. Confusion surrounding a trunk addressed to James Syme Esq., Edinburgh, left in the coach office at the Turf Hotel one evening in September 1825, was enough to spark an investigation, after liquid from the trunk was found oozing across the office floor. Upon opening the trunk, the body of a 19-year-old female was discovered ‘of fair complexion, light eyes and yellow hair’, the delay in shipping having led to her detection.

It wasn’t only Newcastle where discoveries of cadavers were made. In the final month of 1828, prior to a Lecture of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh, Mr Mackenzie was patiently awaiting the delivery of a parcel. Unfortunately for Mr Mackenzie, the public were becoming increasingly aware of the large number of cadavers being transported on the nation’s highways in various packages labelled ‘Glass – Handle with Care’ or ‘Produce’. It is perhaps no surprise then to discover that Mr Mackenzie’s package was regarded as ‘suspicious’ by a vigilant coach driver at the Wheatsheaf Inn, Castlegate, York. The coach driver refused to have the box loaded onto his coach and a crowd soon gathered spreading the rumour that it contained a former inhabitant of St Sampson’s churchyard. With great trepidation, Mr Mackenzie’s box was prized open. There was flesh found inside the trunk, that much is true, but it wasn’t the flesh of a recently resurrected cadaver. Packed neatly within, on this occasion, ready for the Christmas celebrations, were nestled four cured hams.

You’d think that if you‘d been on a recce of the churchyard, found a mound of freshly turned soil indicating a nice fresh burial, then there wouldn’t be any problem in securing a suitable cadaver after that. Think again. Many a bodysnatcher came face to face with a cadaver that they wished they hadn’t started to exhume. Bodysnatching required a certain amount of detachment. The job itself demanded a strong stomach; folding a cadaver in half, or even into three in an attempt to pack it into a suitable container took more than a few drops of alcohol to numb the senses – you were lifting a dead body out of a grave, what’s delicate about that!

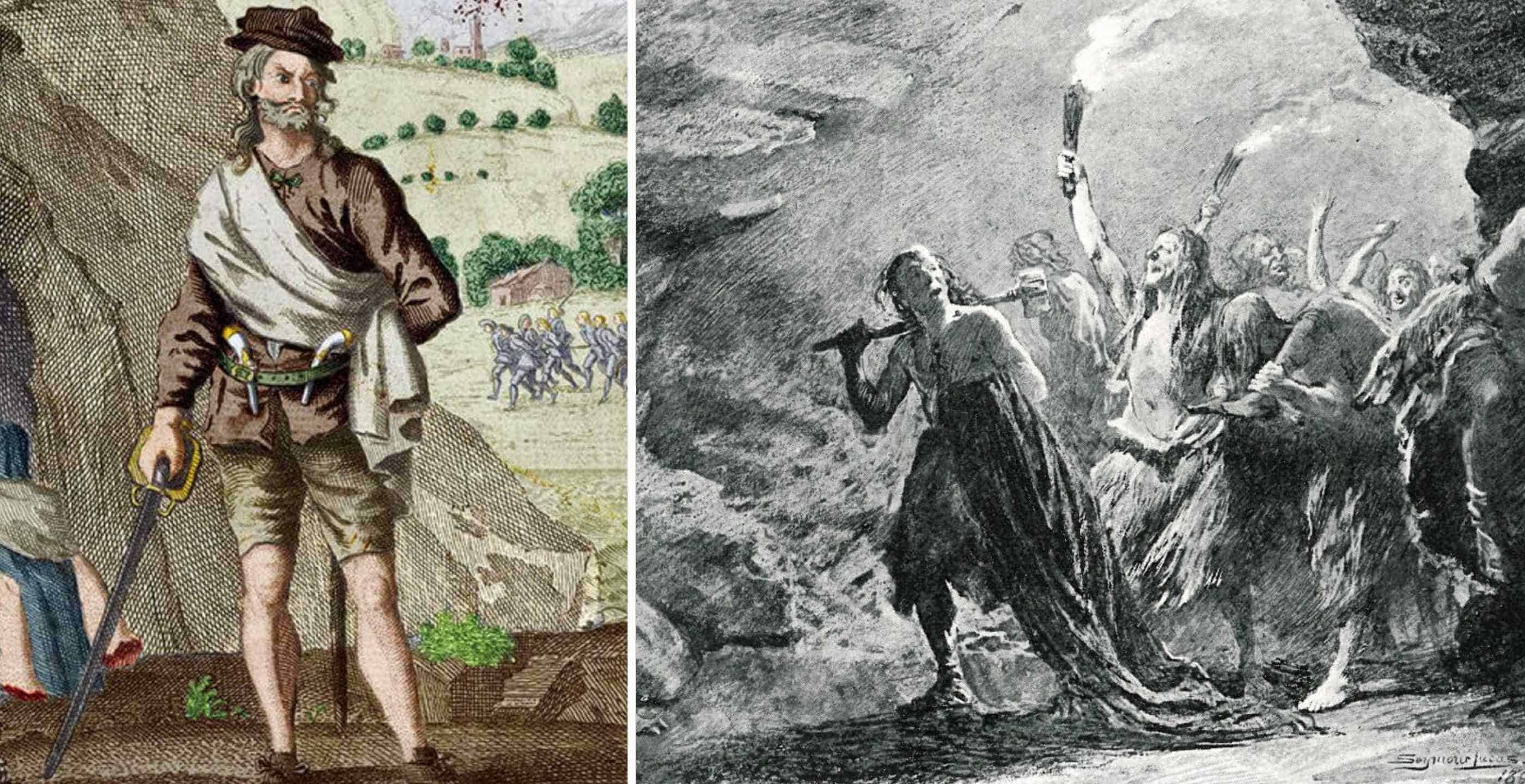

The tale of one bodysnatcher’s dreadful error came to light in 1823, and is retold in a few obscure lines noted in a handful of newspapers. The bodysnatcher in question was known quite aptly as ‘Simon Spade’, a resurrectionist who was working the graveyard at St Martin’s Church in an undisclosed location. Digging away in the dead of night, Simon failed to notice that he was about to make the most fatal of errors. When he’d finished lifting the body from its coffin, just before he was about to fold it in half to pop it into a sack, he brushed the hair away from its face. Words perhaps cannot describe what poor Simon felt when he stared in to the face of that particular cadaver that night. You see, although he had successfully secured a ‘fresh one’ for the dissecting table, he had just exhumed the body of his recently deceased wife!

Edinburgh bodysnatcher Andrew Merrilees, more commonly known as ‘Merry Andrew’, had no scruples in exhuming and selling the corpse of his sister following a quarrel with gang members ‘Mowdiewarp’ and ‘Spune’. A dispute had arisen a few days previous when fellow gang members believed that Merry Andrew had short changed them by 10 shillings, following the recent sale of a cadaver to one Edinburgh surgeon.

Family or not, the recent burial of Merrilees’ sister sparked two separate plans to raid the churchyard in Penicuik where she was buried. Mowdiewarp and Spune suspected that gang leader, Merry Andrew, had a plan of his own to remove and sell the body of his sister, while Merry Andrew had heard about Mowdiewarp and Spune’s potential raid from the man who had hired them out a horse and cart. One the night in question, Merrilees was the first to arrive at the churchyard and quietly took his place behind a nearby headstone, waiting for his fellow gang members to appear. He didn’t have to wait long and remained in hiding while the pair did the hard work exhuming the body. Once the body was out of the ground, Merrilees sprang up, shouting loudly, startling Mowdiewarp and Spune enough to ensure that they dropped the body and made their escape. Success for Merry Andrew, he had his cadaver and hadn’t even broken a sweat.

But what of the bodies that were exhumed that were perhaps past their best? First time bodysnatchers Whayley and Patrick managed to dig up the wrong cadaver after incorrect information was given about a burial in a Peterborough graveyard in 1830. Enough to put them off bodysnatching for the evening, it didn’t however dissuade them altogether from the macabre occupation. One bodysnatcher, the notorious Joseph (Joshua) Naples, went one step further. In a diary kept by Joseph between the period 1811-12 which records the movements of Naples and his associates in the ‘Crouch Gang’, he records that he ’cut off the extremities’ of those cadavers that were exhumed that were perhaps a little ripe. Selling ‘extremities’ to St Thomas’ and Bartholomew’s hospitals in London, it is hoped that Naples and his fellow gang members were made of strong stuff. An entry in the Diary for September 1812 recorded that St Thomas’ refused to buy one cadaver that was being sold because it was too putrid!

Although these exploits paint a rather clumsy and on occasion comical insight into the world of bodysnatching, the threat of exhumation was very real. Churchyards across the country installed a variety of preventative measures to try to stop the bodysnatchers in their tracks. Watch-towers and mortsafes sprang up across the length of the country in an attempt keep parishioners safe in their final resting place.

Cemetery Gun: Also known as a trip gun, would have been positioned over the grave and rigged with trip wires, ready to discharge if anyone dared to try to exhume the corpse within.

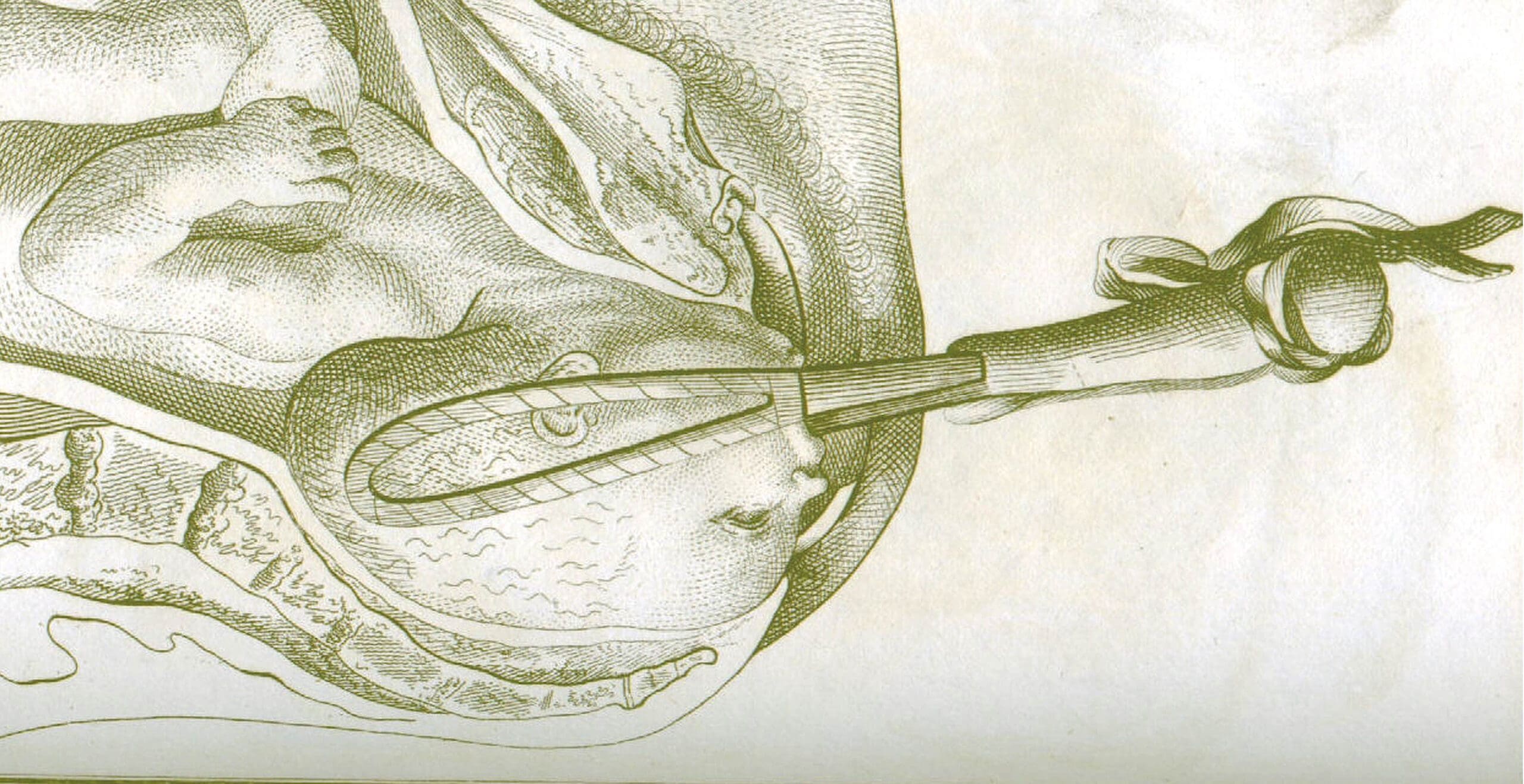

The Coffin Collar, now found at the National Museum of Scotland, was formerly used in Kingkettle, Fife, to deter bodysnatching.

The most gruesome of these preventions were perhaps the cemetery gun and the coffin collar; an iron collar which fastened around the neck of the cadaver, attaching securely to the bottom of the coffin. A few good sharp tugs on the cadaver’s shoulders however would probably have ensured the body was removed from its final resting place; it would all depend on how putrid it was to start with!

Find out more about the world of bodysnatching in Suzie Lennox’s book Bodysnatchers, published by Pen & Sword.

Published: 11th January 2015.