On 15th June 1815, a ball took place in a coach house adjoining the Duke and Duchess of Richmond’s temporary home in Brussels. Known as the Duchess of Richmond’s Ball, it was to become one of the most famous parties in history.

Napoleon had escaped from exile on Elba and was now restored to power in France. The British and their Prussian allies had been gathering their forces ready for action ever since. The Duke of Richmond was in command of a reserve force in Brussels, tasked with protecting the city should Napoleon and the French Army invade.

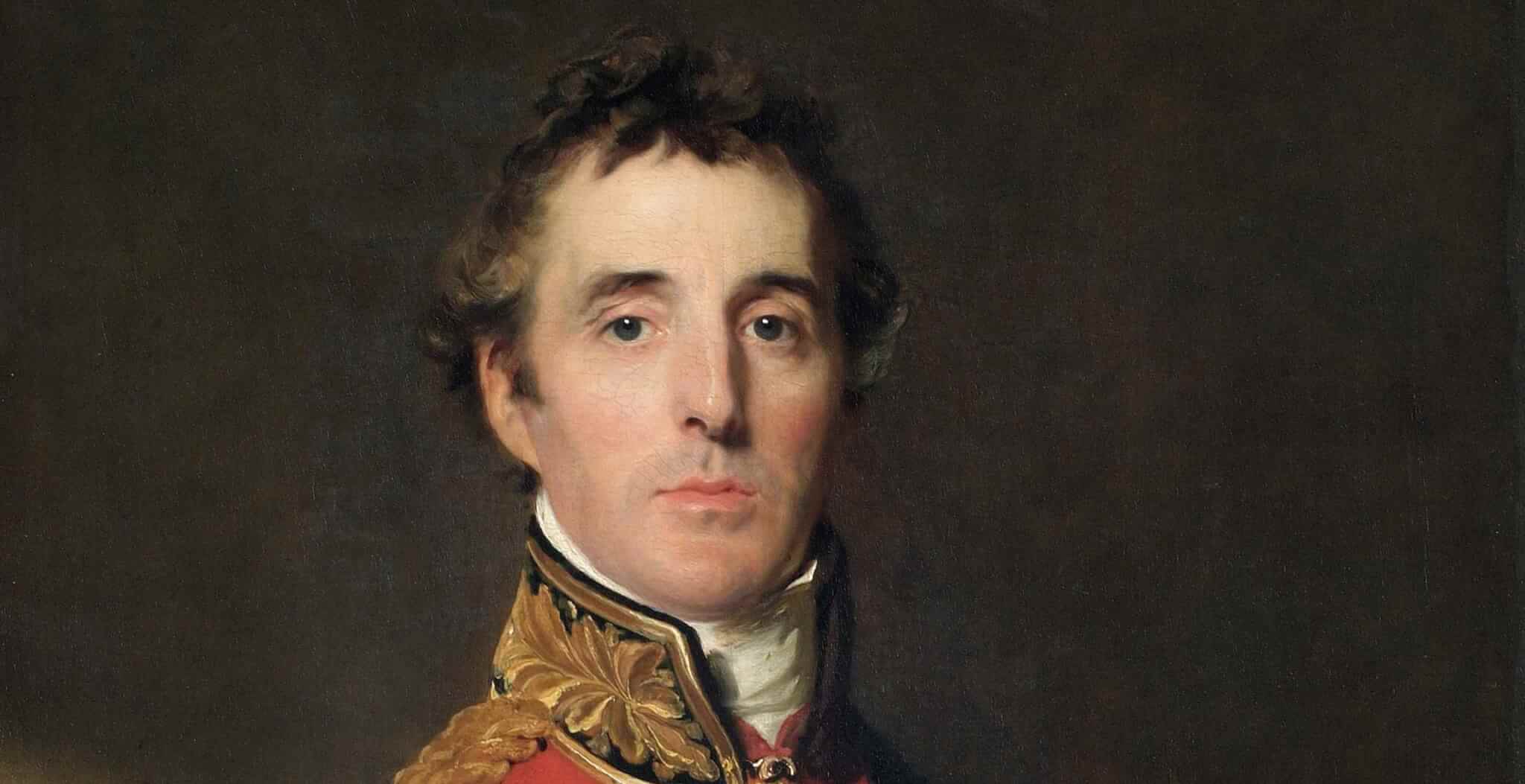

The Duchess of Richmond asked the Duke of Wellington, in charge of the British forces, whether she might hold a ball despite the fluid situation. The Duke replied, “Duchess, you may give your ball with the greatest safety, without fear of interruption.” The Duchess decided on Thursday 15th June as the date for the ball.

However early on the 15th June, Napoleon and his forces crossed the border from France into Belgium.

In the afternoon, the Duke of Wellington received news that Napoleon was on the move and put the army on alert. It may seem odd that such a grand ball, with the Duke of Wellington as one of the guests of honour, was not cancelled at such a perilous time. However Wellington wanted to give the French spies and sympathisers in Brussels the impression that for the British and their Prussian allies, all was as usual.

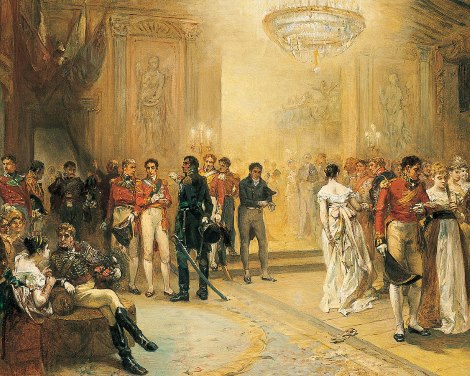

Princes, ambassadors, members of the aristocracy, generals and officers of the Duke of Wellington’s army had all been invited to the ball. The evening was warm, the coach house decorated with swags of silver and gold, and soon the cream of Brussels society began to arrive. The Duchess had arranged for Gordon Highlanders to entertain her guests with sword dances and reels, and the ball was a glittering affair.

The main topic of conversation amongst the crowd was the rumour that the French were advancing. When Wellington arrived late to the ball, this seemed to confirm it.

17-year-old Lady Georgiana Lennox was dancing as the Duke arrived; she immediately went up to him and asked if what she had heard was true. Wellington confirmed that indeed the army was to march early the following morning.

Just before supper, a dispatch arrived for the 23-year-old Prince of Orange, commander of the Dutch-Belgian army, with the news that their Prussian allies had been engaged by Napoleon’s army which had advanced across the Sambre River at Charleroi.

Wellington was now convinced that the attack on Charleroi was Napoleon’s main advance and ordered the Prince and the Duke of Brunswick to return to the field immediately, although he himself stayed on for supper, apparently at ease with the company and fairly relaxed.

A further report from the Prince of Orange left the Duke shocked at the speed of Napoleon’s advance. Immediately after supper, Wellington retired to his host’s study to discuss the situation with his officers. Napoleon had attacked from the east rather than from the west as the Duke had anticipated. Fearing his troops would not be able to stop Napoleon’s advance at Quatre Bras, Wellington identified the small village of Waterloo as the place where he would make a stand.

The ball was beginning to unravel. Officers and men were leaving; mothers, wives and girlfriends cried, embraced and waved their menfolk off to fight. Some didn’t even take the time to change and went off to battle in their knee-breeches and dancing pumps.

The Battle of Quatre Bras took place the following day, 16th June. During that night and the next day Wellington’s forces at Quatre Bras withdrew to just south of Waterloo, where they were joined by the Prussians. On Sunday 18th June, one of the most important battles in British history was fought: Waterloo.

The Duchess of Richmond’s event, as a ball, was a disaster. Although the evening had begun with dancing, music and romance, it had quickly changed into a night of tearful goodbyes. Over the next few days and before victory was finally achieved at the Battle of Waterloo, eleven of the Duchess of Richmond’s guests would be dead, including Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Picton, the Duke of Brunswick, Lord Hay, Sir Alexander Gordon and Sir William Ponsonby.

The ball has been immortalised in paintings, on screen and in literature, including Thackery’s Vanity Fair, Sir Walter Scott‘s Paul’s Letters to his Kinsfolk, Georgette Heyer’s An Infamous Army and Bernard Cornwell’s Waterloo, part of the Sharpe series.

‘There was a sound of revelry by night,

And Belgium’s capital had gathered then

Her Beauty and her Chivalry, and bright

The lamps shone o’er fair women and brave men;

A thousand hearts beat happily; and when

Music arose with its voluptuous swell,

Soft eyes looked love to eyes which spake again,

And all went merry as a marriage bell;

But hush! Hark! A deep sound strikes like a rising knell!…

…Ah! then and there was hurrying to and fro,

And gathering tears, and tremblings of distress,

And cheeks all pale, which but an hour ago

Blushed at the praise of their own loveliness;

And there were sudden partings, such as press

The life from out young hearts, and choking sighs

Which ne’er might be repeated; who could guess

If ever more should meet those mutual eyes,

Since upon night so sweet such awful morn could rise!

And there was mounting in hot haste: the steed,

The mustering squadron, and the clattering car,

Went pouring forward with impetuous speed,

And swiftly forming in the ranks of war;

And the deep thunder peal on peal afar;

And near, the beat of the alarming drum

Roused up the soldier ere the morning star;

While thronged the citizens with terror dumb,

Or whispering, with white lips—‘The foe! They come! they come!’’

The Eve of Waterloo from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage by Lord Byron

Published: 21st November 2014.