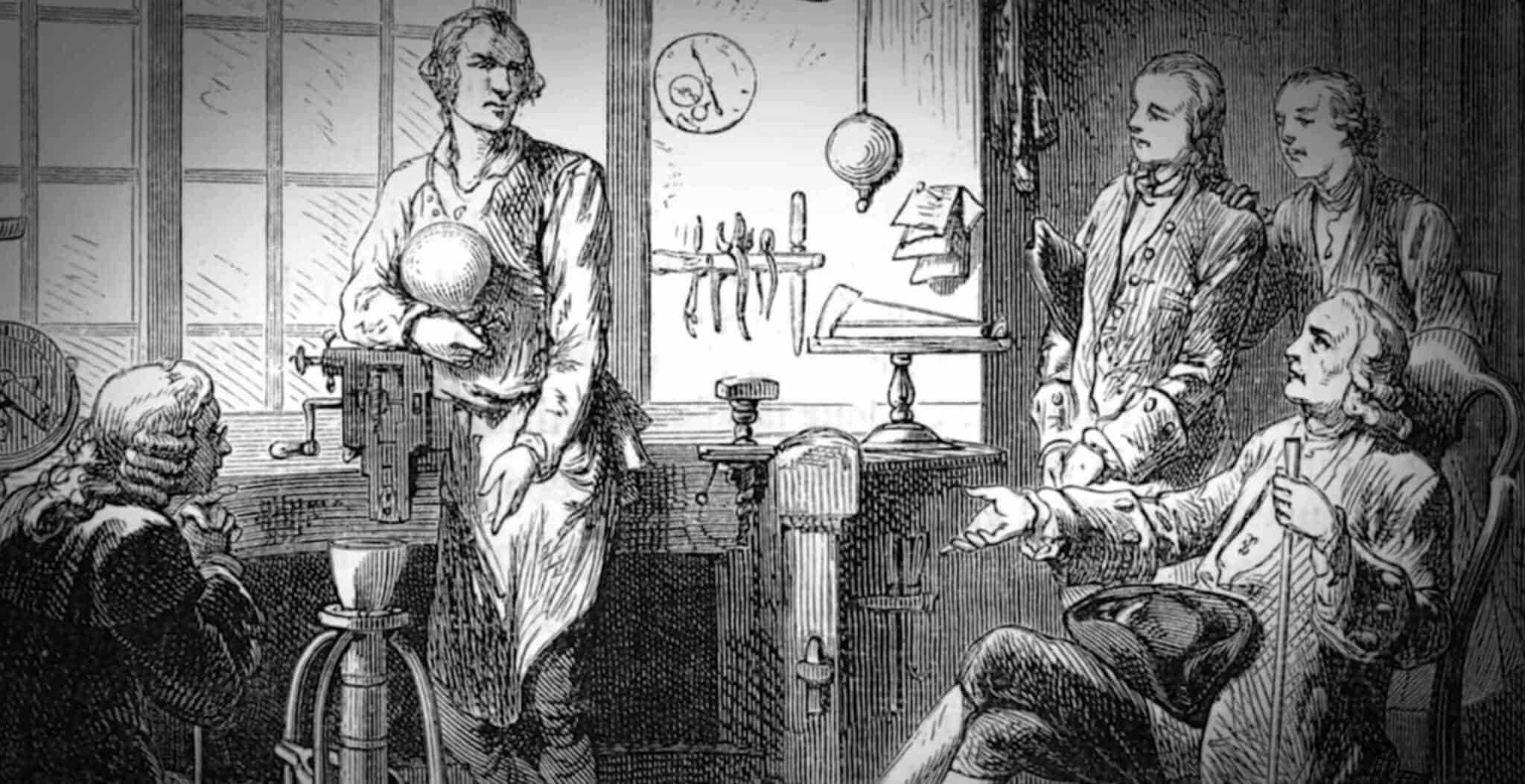

On 9th October 1779 a group of English textile workers in Manchester rebelled against the introduction of machinery which threatened their skilled craft. This was the first of many Luddite riots to take place.

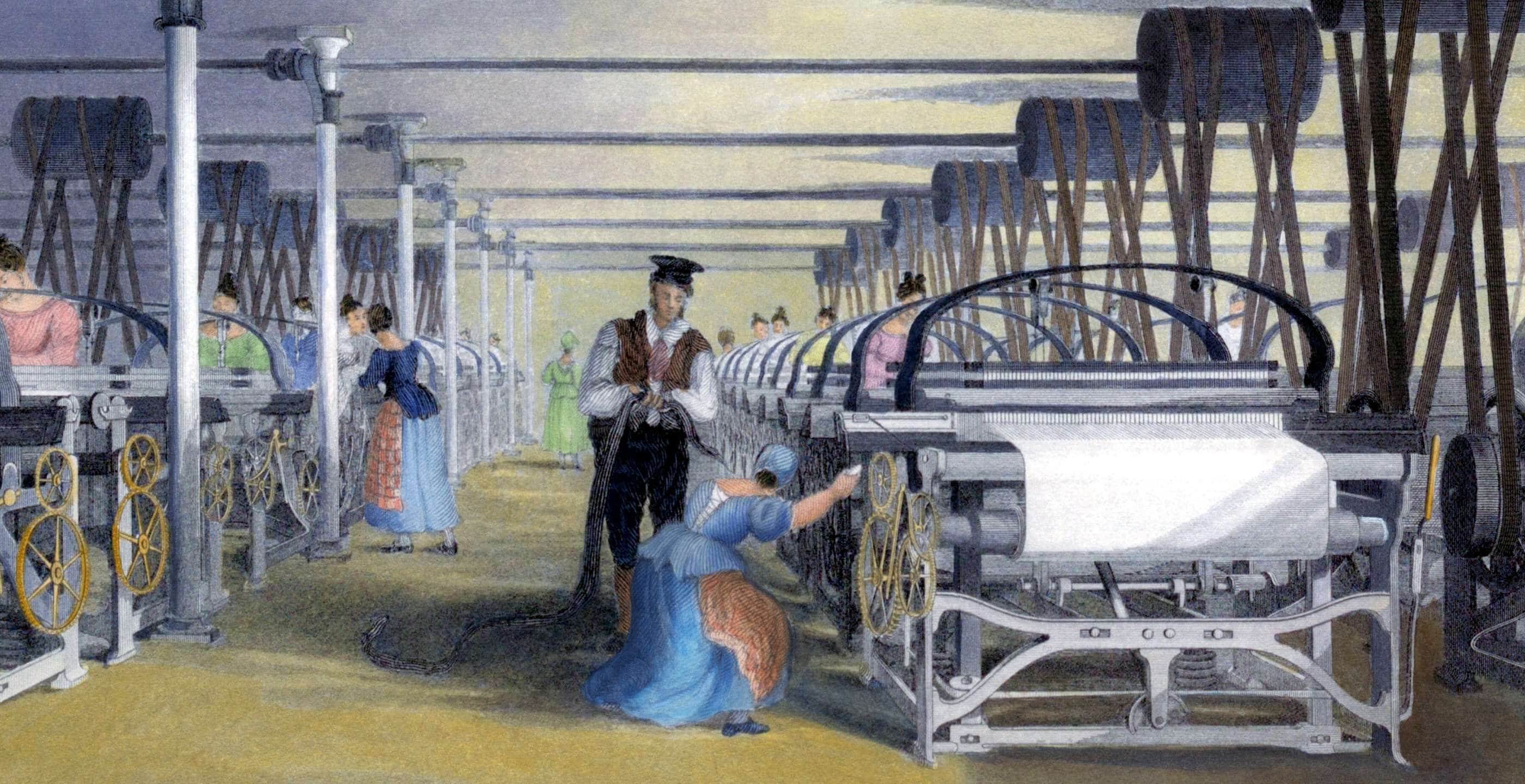

The word ‘Luddites’ refers to British weavers and textile workers who objected to the introduction of mechanised looms and knitting frames. As highly trained artisans, the new machinery posed a threat to their livelihood and after receiving no support from government, they took matters into their own hands.

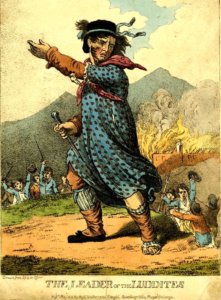

Today the term ‘Luddite’ is often used to generalise people who do not like new technology, however it originated with an elusive figure called Ned Ludd. He was said to be a young apprentice who took matters into his own hands and destroyed textile apparatus in 1779. The groups of workers that followed in his footsteps said they were taking orders from “General Ludd” and issued manifestos using his name. That being said, there is no evidence of his actual existence, with Ned Ludd assuming a more mythical ‘Robin Hood‘ reputation, he would become the legendary character others would use to create a namesake for their cause. Ned Ludd followers the Luddites were using a name to shock the government into submission. Would their tactics prove successful?

The Luddites were not, as has often been portrayed, against the concept of progress and industrialisation as such, but instead the idea that mechanisation would threaten their livelihood and the skills they had spent years acquiring. The group went about destroying weaving machines and other tools as a form of protest against what they believed to be a deceitful method of circumventing the labour practices of the day. The replacement of people’s skilled craft with machines would gradually substitute their established roles in the textile industry, something they were keen to prevent, rather than simply halting the advent of technology.

The textile workers and weavers were actually skilled, well-trained middle-class workers of their time. After working for centuries maintaining good relationships with merchants who sold their products, the introduction of machinery not only superseded the need for handcrafted garments but also initiated the use of low skilled and poorly payed labourers in larger factories. This transition would prove disastrous for the artisans of their craft, who had spent years perfecting and honing their skills only to be replaced by less skilled, underpaid workers operating machinery.

In an attempt to halt or at least make the transition smoother, the Luddites initially sought to renegotiate terms of working conditions based on the changing circumstances in the workplace. Some of the ideas and requests included the introduction of a minimum wage, the adherence of companies to abide by minimum labour standards, and taxes which would enable funds to be created for workers’ pensions. Whilst these terms do not seem unreasonable in the modern day workplace, for the wealthy factory owners, these attempts at bargaining proved futile.

The Luddite movement therefore emerged when attempts at negotiation failed and their valid concerns were not listened to, let alone addressed. The Luddites activity emerged against a backdrop of economic struggle from the Napoleonic Wars which impacted negatively on the working conditions already experienced in the new factories. With the advent of new technology and more low skilled workers, this issue was exacerbated.

In the eighteenth century, the working classes were not likely to rebel against the government, largely due to the fear of reprisals as punishment was severe. The main preoccupation for workers, as was the case for the Luddites, was being able to make a living but as the Industrial Revolution began to threaten the status quo, so too did the levels of discontent rise amongst the workers. The Luddites became typical for the period, rebelling against the threats to their livelihood, attempting to find a position in which they could barter for better conditions and wages and most importantly not lose their place in the chain of production.

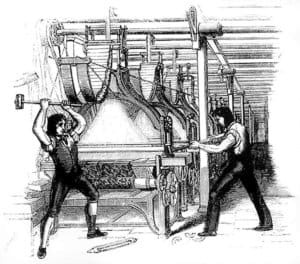

The foundations for the Luddites began in the late 1700’s but the first noticeable riots occurred in 1811. For those who had attempted to negotiate with the factory owners and the government, their pleas had not been heard. The tactics used appeared quite radical; however considering the fact there were no unions to fall back on, the message of defiance against a known threat to their livelihood took the form of breaking machinery. The intention was to put employers under pressure in order to cave into their demands, however the response they were met with was swift and brutal.

Initially the response from the government was to put through the Protection of Stocking Frames Act in 1788 which essentially increased the penalties for destroying factory equipment. This did little to hinder Luddite activity and on 11th March 1811 the first major Luddite riot took place in Arnold, Nottingham. This became one of many, as the movement swept across the country with weavers burning mills and destroying factory equipment. In 1811 alone, hundreds of machines were destroyed or broken and the government soon began to realise that neither the movement nor the frustration of the people was dissipating.

The group would often meet at night, somewhere isolated near the industrial towns where they worked in order to organise themselves. Much of the activity surrounded the Nottinghamshire area in late 1811 but was extended to Yorkshire the following year and to Lancashire in March 1813. The activity was organised by smaller groups of men who felt their livelihoods were at stake. As there was no central force organising the Luddites, the movement was able to sweep the country easily as many families’ lives were being compromised by the industrialisation process.

The attacks used sledgehammers and in some cases escalated to gunfire when the factory owners responded by shooting the protesters. Whilst the workers hoped the uprising would encourage a ban of weaving machines, the British government had no such plans and instead made machine breaking punishable by death.

The wealth of the factory owners meant that the British government were very responsive to the concerns of the owners rather than the workers. In accordance with this, they sent around 14,000 soldiers into the affected areas, forcing Luddites to battle with the British Army, such as at Burton’s Mill in Middleton, Rochdale, Greater Manchester. They also attempted to suppress the activity by infiltrating the group with spies. The unrest was escalating and there seemed to be no end in sight.

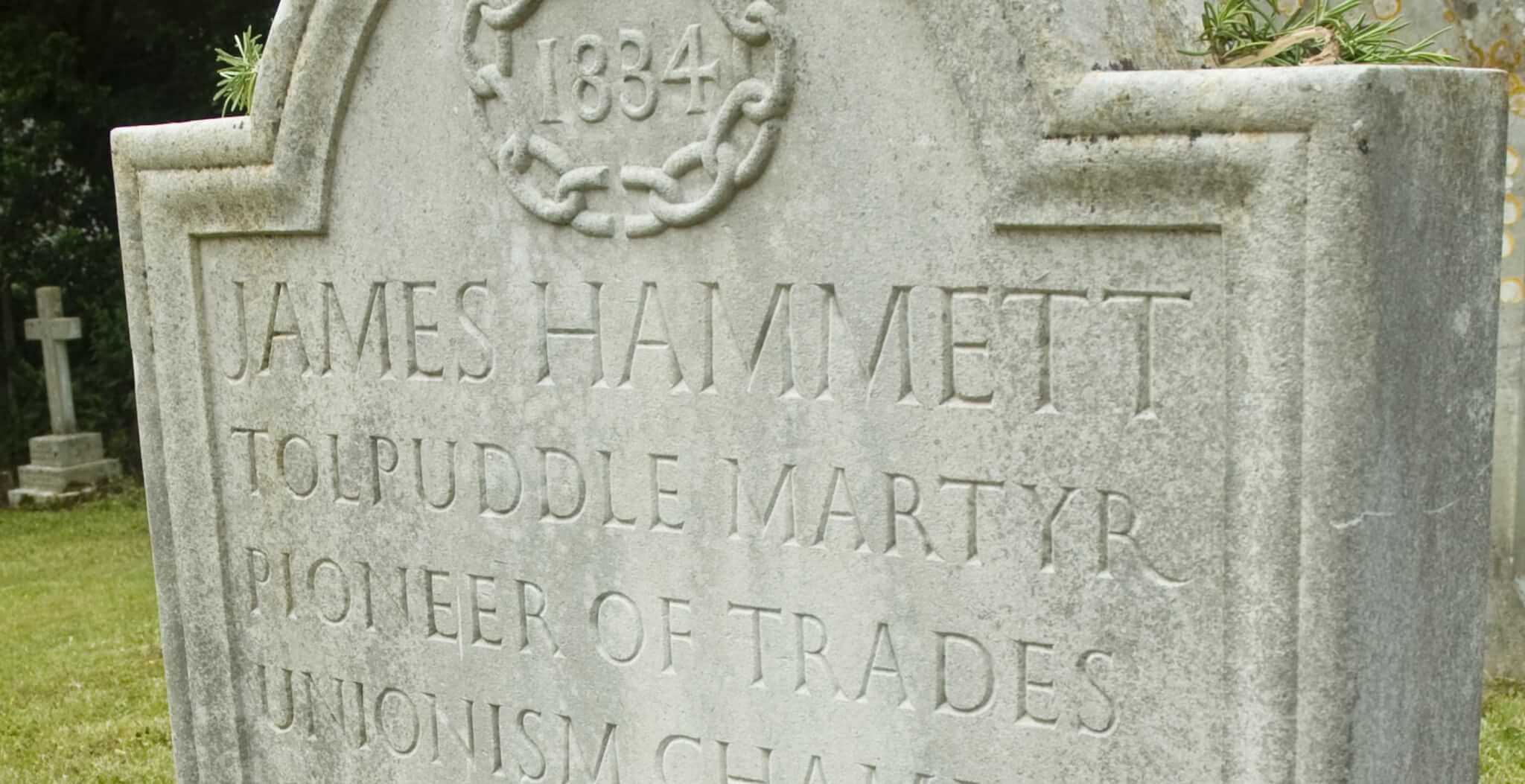

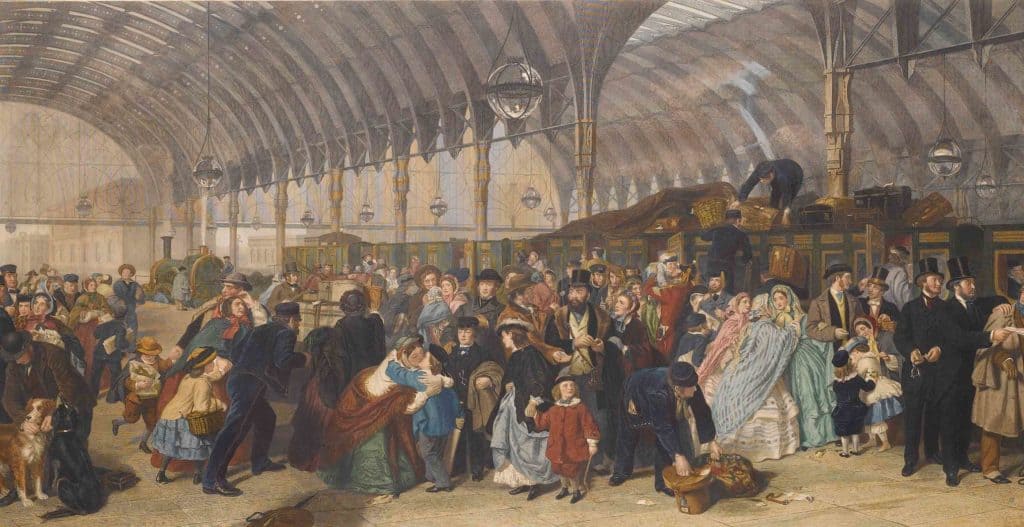

In April 1812 some of the Luddites were gunned down at a mill near Huddersfield, Yorkshire. The army were on the offence and began to round up the Luddites, transporting large groups of them to either be hanged or taken to Australia to serve their punishment. The harsh response which resulted in imprisonment, death or being sent across the world was enough to suppress the actions of the group. By 1813, the activities had dwindled and only a few years later the group had vanished. The last recorded Luddite activity was carried out by a unemployed stockinger in Nottingham called Jeremiah Brandreth who led the Pentrich Rising. Although not specifically related to machinery, it was the last fight of its kind before the tragic circumstances of the Industrial Revolution prevailed in the country.

Sporadic outbreaks of violence would proceed through the years in various forms, not always related to factory work but in retaliation for the industrialisation process affecting many established traditions and practices. The Luddites were the pioneers in this struggle against machinery replacing the work of men.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 6 October 2018.