Did you know that you could be imprisoned for shaving your moustache? Between 1860 and 1916, every soldier in the British Army was forbidden from shaving his upper lip or else it would have been considered a breach of discipline.

According to the Oxford dictionary, it was in 1585 that the word ‘moustache’ was first recorded in the translation of the French book, The nauigations, peregrinations and voyages, made into Turkie. The moustache would need close to another 300 years to become the emblem of the British Empire, the empire which in its’ heyday ruled a quarter of the world’s population.

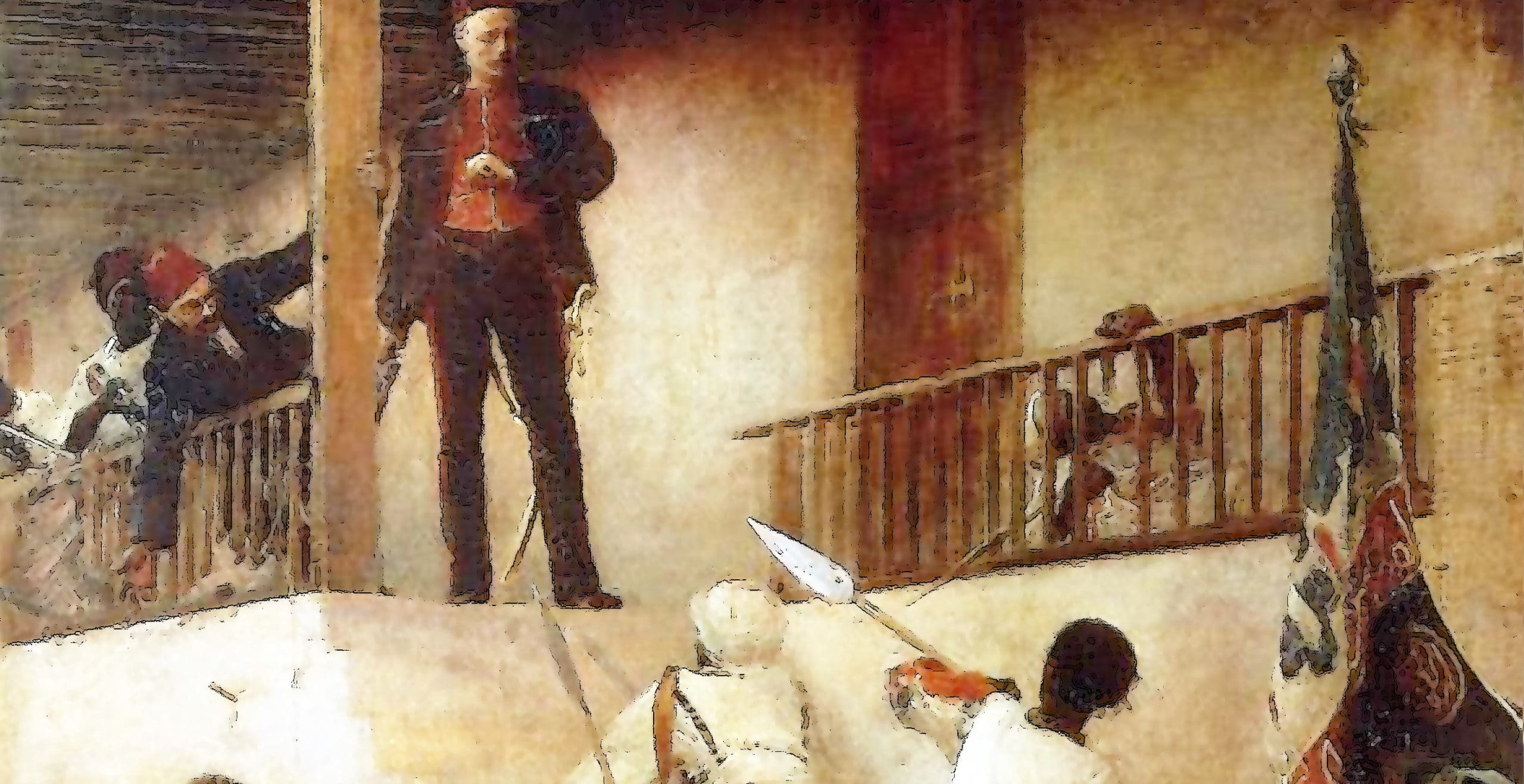

During the Napoleonic Wars in the 1800s, British officers were inspired by the coxcombical Frenchmen with their whiskers being ‘appurtenances of terror’. In the newly colonized lands of India, the moustache was a symbol of male prestige. Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, commemorated his victory over the East India Company with a painting depicting the clean-shaven British soldiers as if they looked like girls or at least creatures ‘who are not fully male’.

Whether it was this apparent contempt for the clean-shaven British by the Indian men, the need to assert the supremacy of the Imperial race or simply because they liked this new symbol of masculinity, British soldiers began to appropriate this Indian sign of virility. Thus began what became known as the ‘moustache movement’. In 1831, much to their delight, the 16th Lancers of the Queen’s Army were permitted to wear moustaches.

However, growing a moustache was still condemned by many as ‘going native’ and the British were discouraged from adopting such fashion. In 1843, army officer James Abbot’s large moustaches raised eyebrows despite his heroic efforts in the far-flung corners of the Indian subcontinent. However around this time there was notably one public figure who dared to wear the moustache: Mr George Frederick Muntz, a Member of Parliament for Birmingham.

In India, Governor General Lord Dalhousie was not in favour of ‘capillary decorations’. In his private letters Dalhousie wrote that he ‘hate to see an English soldier made to look like a Frenchman’.

The Civil Service, on the contrary, welcomed such decorations. The press too echoed similar sentiments. By the 1850s, prestigious journals such as The Westminster Review, Illustrated London News and The Naval & Military Gazette commented extensively, giving birth to a ‘beard and moustache movement’. In 1853, a beard manifesto was published in Charles Dickens’ widely read magazine Household Words, entitled ‘Why Shave?’. This vociferous movement promoted the benefits of facial hair so well that by 1854 Lord Frederick FitzClarence, Commander in Chief of the Bombay army of the East India Company, gave orders making moustaches compulsory for the European troops of the Bombay unit.

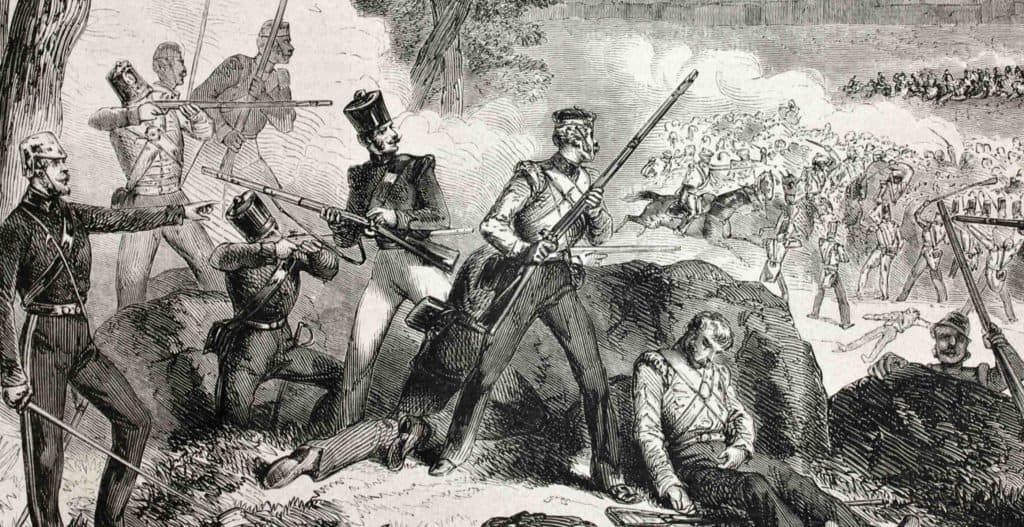

The Crimean War started in October 1853 and British troops were permitted to forego the razor in order to protect themselves from the bitter cold and attacks of neuralgia. When the war ended three years later, the sight of the returning soldiers invoked inspiration. Queen Victoria wrote in her journal dated 13th March 1856 that the soldiers disembarking ‘were the picture of real fighting men……They all had their long beards and were heavily laden with large knapsack’.

During the war in Crimea, beards, moustaches and sideburns became symbols of courage and determination. Britons back home started sporting similar facial hair styles in solidarity with their heroes on the battlefield.

Sergeant John Geary, Thomas Onslow and Lance Corporal Patrick Carttay, 95th Regiment (Derbyshire) Regiment of Foot, Crimean War

Sergeant John Geary, Thomas Onslow and Lance Corporal Patrick Carttay, 95th Regiment (Derbyshire) Regiment of Foot, Crimean War

By 1860, moustaches had become mandatory in the British Army. Command No. 1695 of the King’s Regulations read: ‘……..The chin and the under lip will be shaved, but not the upper lip. Whiskers if worn will be of moderate length’

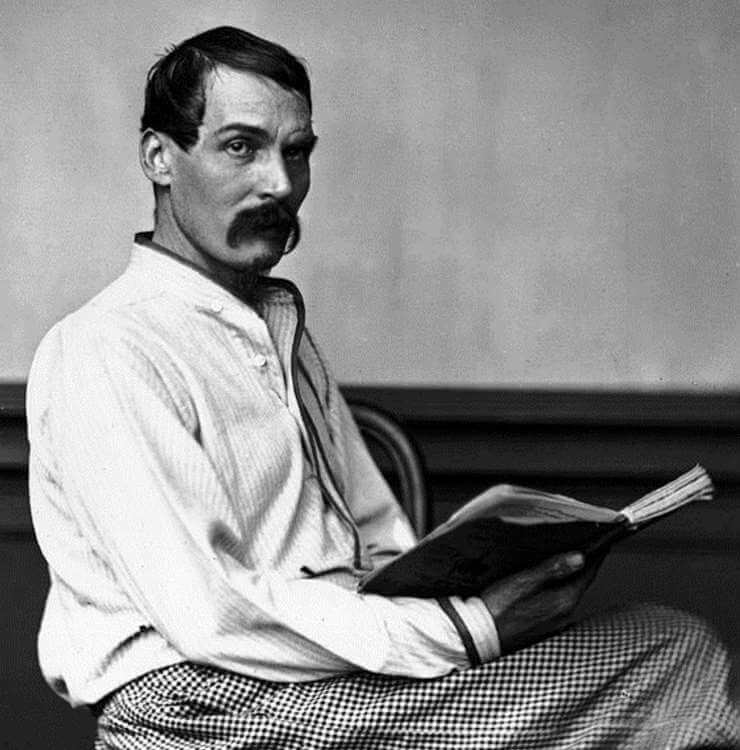

The unshaven ‘upper lip’ thus became synonymous with military uniform and service. Be it General Frederic Thesiger, who came to prominence during the Zulu Wars in the late 1870s, or Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts who became one of the most successful commanders in the nineteenth century, or the great African explorer Sir Richard Burton, all had a stiff upper lip decorated with a moustache. Burton in fact, during his teenage years at Trinity College, Oxford, challenged a fellow student to a duel as the latter dared to mock his moustache.

Not only in the army but after the mid 1850s, moustaches also stormed into British civil society. The moustache cup was invented in the 1860s to keep moustaches dry while drinking tea. In 1861, an article in the British Medical Journal suggested that America lost an aggregate 36 million working days in an average year just by shaving. Even in the colonies, it was social death for a British man if he forgot to curl the ends of his moustache. At the gentlemen’s club, to present yourself with a shaved upper lip was considered as shameful as forgetting to put your trousers on.

However by the end of the 1880s, the popularity of moustaches was in decline. Fashionable men in London started preferring a clean shave. Facial hair was considered to harbour germs and bacteria. Shaving beards, while patients were hospitalized, became a norm. In 1895, American inventor King Camp Gillette (he himself with a prominent moustache) came up with the idea of disposable razor blades. The practice of being hair free had never been so cheap and easy.

Another serious blow to beards and moustaches came at the onset of the First World War. It was difficult to put your gas mask on if you had facial hair, as the seal would work only on a hair-free skin. Finding clean water at the front was tough too, so shaving became a luxury. Also, as many as 250,000 boys under the age of 18 fought for Britain in the Great War. These recruits were too young to sport a moustache; all they could manage was a thin mousey streak. Even before the war started in 1914, there were reports regarding the infringement of the military order that a moustache had to be worn.

An army council was set up to debate this further and on 8th October 1916, it was decided that moustaches would no longer be mandatory in the British army. The King’s Regulations were amended to delete ‘but not the upper lip’. The decree was signed by General Sir Nevil Macready, who himself hated moustaches and who dropped into a barber shop that very same evening to set the example.

Later as Britain’s once indomitable empire started to falter, the moustache too beat a retreat. Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival, blamed for the British defeat at Singapore, had an uninspiring moustache. Even Prime Minister Anthony Eden, whose mishandling of the Suez crisis in 1956-57 led to a permanent loss of British prestige as a superpower, had a barely visible moustache.

The fate of the moustache could be seen to be intertwined with that of the Empire. As the red mark on the map, which at its zenith was seven times the size of the Roman Empire, was reduced to few insignificant dots, so were the decorated upper lips, a bygone symbol of imperial supremacy.

By Debabrata Mukherjee. I am an MBA graduate from the prestigious Indian Institute of Management (IIM), currently working as a consultant for Cognizant Business Consulting. Bored with mundane corporate life, I have resorted to my first love, History. Through my writing, I want to make history fun and enjoyable to others as well.