The V Sign may appear to be a transparent symbol of peace, but its genesis is mazy and its meaning hazy. The symbol was seen across Europe during World War II, from wall graffiti to plane formations. Belgian Minister of Justice, Victor de Laveleye, advocated the V Sign, representing the French ‘victoire’/victory and Dutch ‘vrijheid’/freedom.

Inspired, the BBC initiated its V For Victory campaign. Foreign language broadcasts began with the opening four notes of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony V, The Fifth Symphony, since known as the Victory Symphony. These notes neatly parallel the Morse Code pattern for the letter V (3 dots and a dash). Incidentally, the Victory Symphony was composed between 1804 and 1808 – by which time Beethoven himself was deaf. In diaries and letters, he attests he had developed labyrinthitis, tinnitus, and difficulty identifying words and high sounds. He begged friends to keep his deafness a ‘profound secret’. He was shocked at those who did ‘not notice my condition at all’ but considered him ‘absent-minded’.

Beethoven had ‘both conductive and sensorineural loss’, Bella Bathurst informs in her book, Sound. Conductive loss occurs from damage to the ‘mechanical processes’ of the outer and middle ears, which deliver sound-waves to the inner ear, which in turn transforms these into signals the brain can decipher. Thus, ‘the ear receives, the brain processes’. Prudent for this article, Bathurst analogises this as ‘a physical Enigma code’…

World War I

The Enigma machine was invented for Germany towards the end of WWI. British code-breakers’ work to decode the transmissions was invaluable to the Allied victory. Likewise, the inner ear’s translations are essential to hearing and comprehension and indeed survival. WWI soldiers reported their hearing loss was due to reluctance to use issued ear protection, not least because hearing a grenade pin drop was the difference between life and death.

An estimated 30,000 soldiers were deafened during WWI, according to historian Peter Brown. Contemporary poetry indicates some of the last sounds they heard clearly:

‘ […] deaf even to the hoots/ Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind’ (Dulce Et Decorum Est, Wilfred Owen)

‘In the sky/ The larks, still bravely singing, fly/ Scarce heard amid the guns below’ (In Flanders Fields, John McRae)

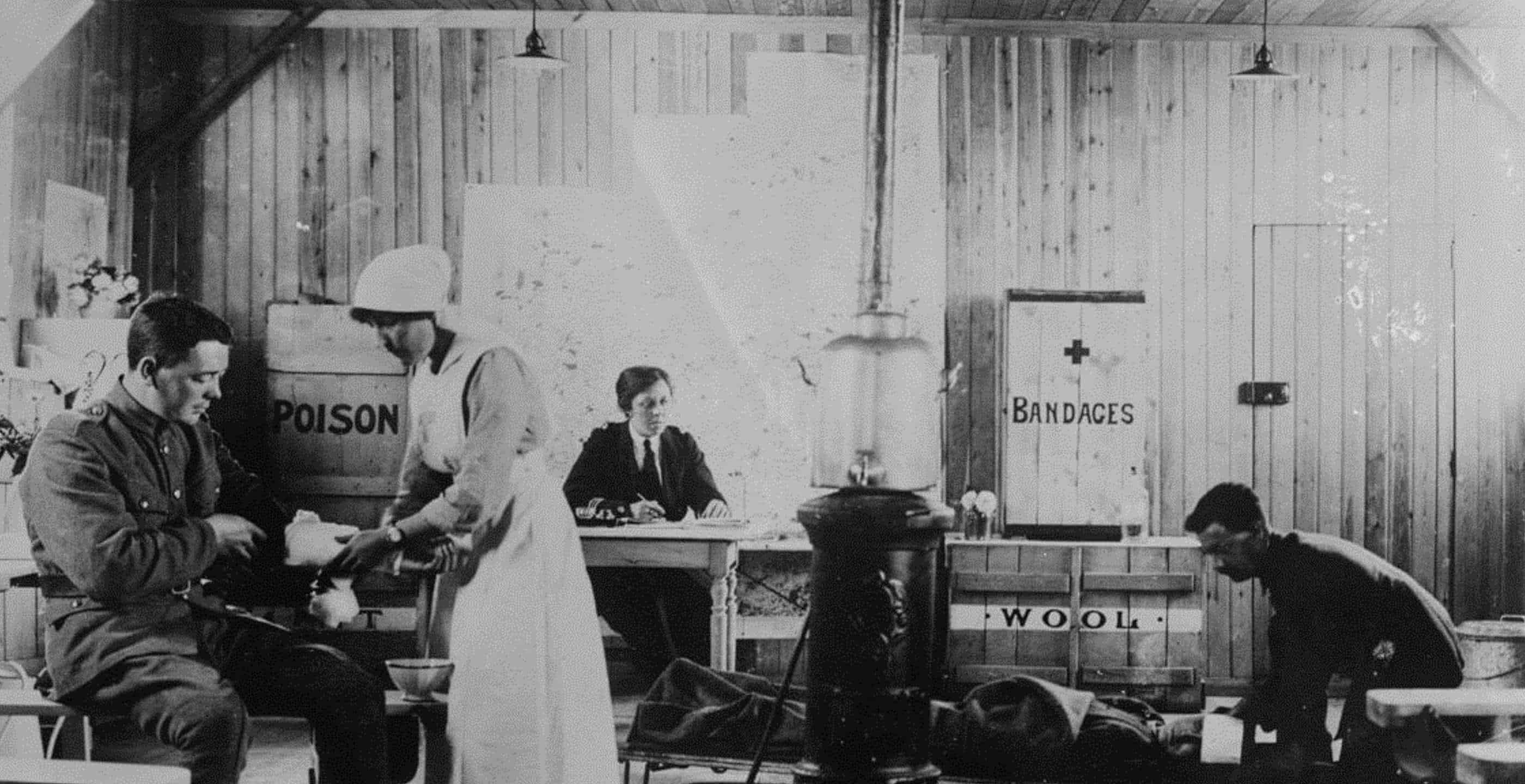

Deafened soldiers received half the disability pension of those who had been blinded but 31 UK centres were established to teach lip-reading. Contrastingly, in America, many professionals considered soldiers’ deafness to be fictitious. Doctors and psychiatrists claimed it was psychosomatic, due to ‘a lack of moral fibre’, Bathurst reports. US army protocol was to treat sufferers with sodium pentothal, a chemical truth serum. This was to force a confession of dishonesty rather than alleviate pain and loss.

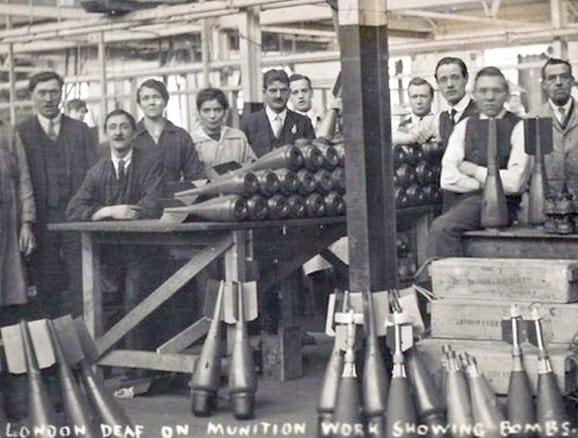

Deaf men were keen to “share the Empire’s work”, as one man wrote to Lord Kitchener. In 1917, as manpower dwindled, a French newspaper reported deaf people had been trained as munitions workers. Britain’s Margate Deaf School reported 8 pupils left for similar employment. They made everything from testing shells and fuses to tools and wheels. Furthermore, a deaf volunteer battalion was apparently trained in drill and tunnel digging.

© Action on Hearing Loss.

© Action on Hearing Loss.

Despite this inclusion, devastating losses occurred on the Home Front due to a disastrous lack of awareness. A number of deaf people were “randomly shot while walking home from work, cycling or generally getting on with life”, as historian Norma McGilp informs. Why? As the BDT reported, they were “unable to hear the challenges of the sentries” and so, McGilp says, “when they continued to walk, they were shot”.

Some managed to join the army. Harry Ward, Gomer Jones and Frederick Morffew were a few. Ward signed on with the Royal Munster Fusiliers and did basic training at the Curragh Camp in Ireland. Private Jones, profoundly deaf since infancy, was the best marksman in his company. A former road worker from Petersham, Morffew served for over a month before discovery of his deafness led to discharge. Determined, he joined the labour corps and was posted to France. His granddaughter commemorated,

“You were a hero, and I salute you, because I think you must have been some special sort of person. I’m glad that you were in my family.”

World War II

Adolf Hitler’s rampage against “undesirables” included disabled people – of which many deaf Germans did not count themselves a part. Some formed a paramilitary Sturmabteilung/SA group called the Reich Union of the Deaf. They marched in support of the Nazi ideology, spread its propaganda and actively ostracised deaf Jews. The group was eventually disbanded by Goering.

Approximately 17,000 deaf Germans were sterilised in Nazi-occupied Germany.

Of 600 deaf Jews who lived in Berlin, 34 survived.

In 1939, whilst the persecution of deaf Germans and Jews began, the International Games for the Deaf took place in Sweden. Great Britain was one of 13 participants. On the eve of Chamberlain’s declaration of war, all British citizens were ordered home from Sweden for their safety.

Soon after, badges were issued to as many deaf people as possible: a luminous circle on which ‘DEAF’ was written. Deaf people were instructed to point their badges down outdoors, lest they attracted enemies in the skies.

Significantly, radio and music, the time’s foremost medias, were lost on the Deaf community, which relied on friends and families to relay news. Newspapers and moving pictures were essential.

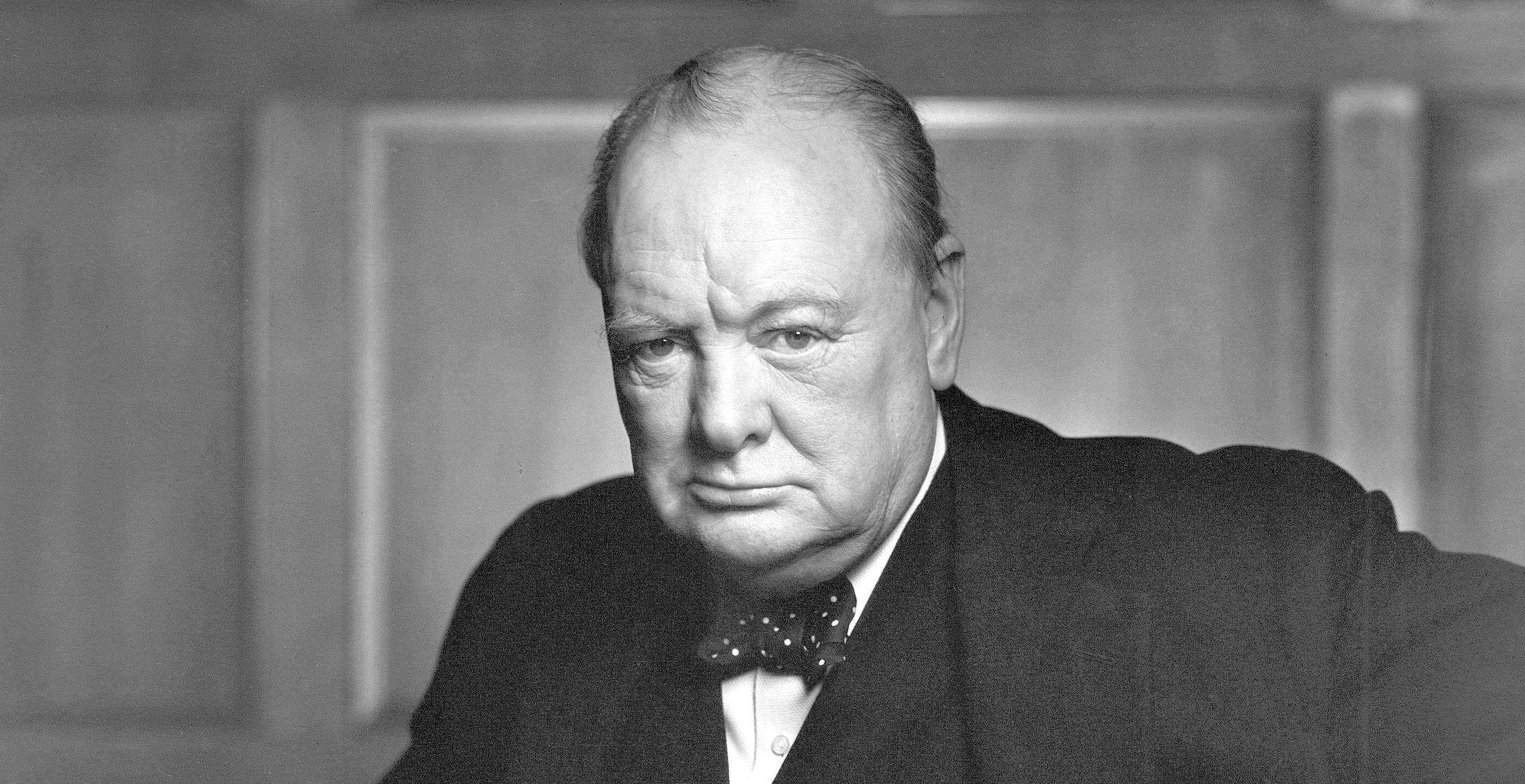

Following the popularity of the BBC’s V for Victory campaign, Churchill adopted the sign in 1941. He alternated the palm-forward V of virtue and dorsal-hand V of vice at whim, projecting victorious peace and hostility for the Nazi enterprise. However, individuals such as Vera Hunt reported that families used to hide newspapers to put fear at bay, excluding deaf people from this solidarity. Furthermore, the V sign is not exactly transferable into British Sign Language. In BSL, it represents ‘2’ (which, granted, connects to the war under discussion).

Today

Currently, the normal pain threshold is marked at around 120dB. British standards mandate that employers must not allow prolonged noise levels over 85dB in the workplace. A pneumatic drill two metres away measures 126dB. An alarm clock is 90dB. A gun-blast measures at about 140dB, the same as hearing a jet plane taking off about 40m away.

Hearing damage remains a ‘systemic, endemic’ consequence of working in the armed forces, according to Professor Mark Haggard, honorary vice-president of Deafness Research UK. Exposure to close-combat fighting, roadside devices and low-flying coalition aircraft has left over two-thirds of British troops who fought in Afghanistan with severe to permanent hearing loss. A study conducted by Deafness Research UK and the Ministry of Defence found that of 1,254 troops following a six-month tour, 865 displayed signs of severe hearing damage. 69% of the Royal Marines showed signs of NIHL (noise-induced hearing loss).

There is only one army in the world that does not exclude deaf people. The Israeli Defence Force trains and employs deaf soldiers. Interpreters are provided during training. Often, these soldiers are employed for cartography and office work.

Whilst deaf people are otherwise globally excluded from the services, it is statistically only a matter of time before many soldiers develop hearing damage and loss.

By Eve Bolt. Eve is an English graduate from London, currently pursuing editorial adventures in the book publishing world. Previously, she was able to apply her fascination with language and passion for accessibility as a British Sign Language Communication Support Worker and as founder of the Interpretation & Translation department at a long-established transcription agency. When she’s not foraging for chocolate or working as a professional Lap for her cats, she may be found writing, doing yoga and kickboxing, reading mythology or researching etymology (or, occasionally, attempting to do all these at once).

Published: April 23, 2021.