“I had a little bird

its name was Enza

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.”

(1918 children’s playground rhyme)

The ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic of 1918 was one of the greatest medical disasters of the 20th century. This was a global pandemic, an airborne virus which affected every continent.

It was nicknamed ‘Spanish flu’ as the first reported cases were in Spain. As this was during World War I, newspapers were censored (Germany, the United States, Britain and France all had media blackouts on news that might lower morale) so although there were influenza (flu) cases elsewhere, it was the Spanish cases that hit the headlines. One of the first casualties was the King of Spain.

It was nicknamed ‘Spanish flu’ as the first reported cases were in Spain. As this was during World War I, newspapers were censored (Germany, the United States, Britain and France all had media blackouts on news that might lower morale) so although there were influenza (flu) cases elsewhere, it was the Spanish cases that hit the headlines. One of the first casualties was the King of Spain.

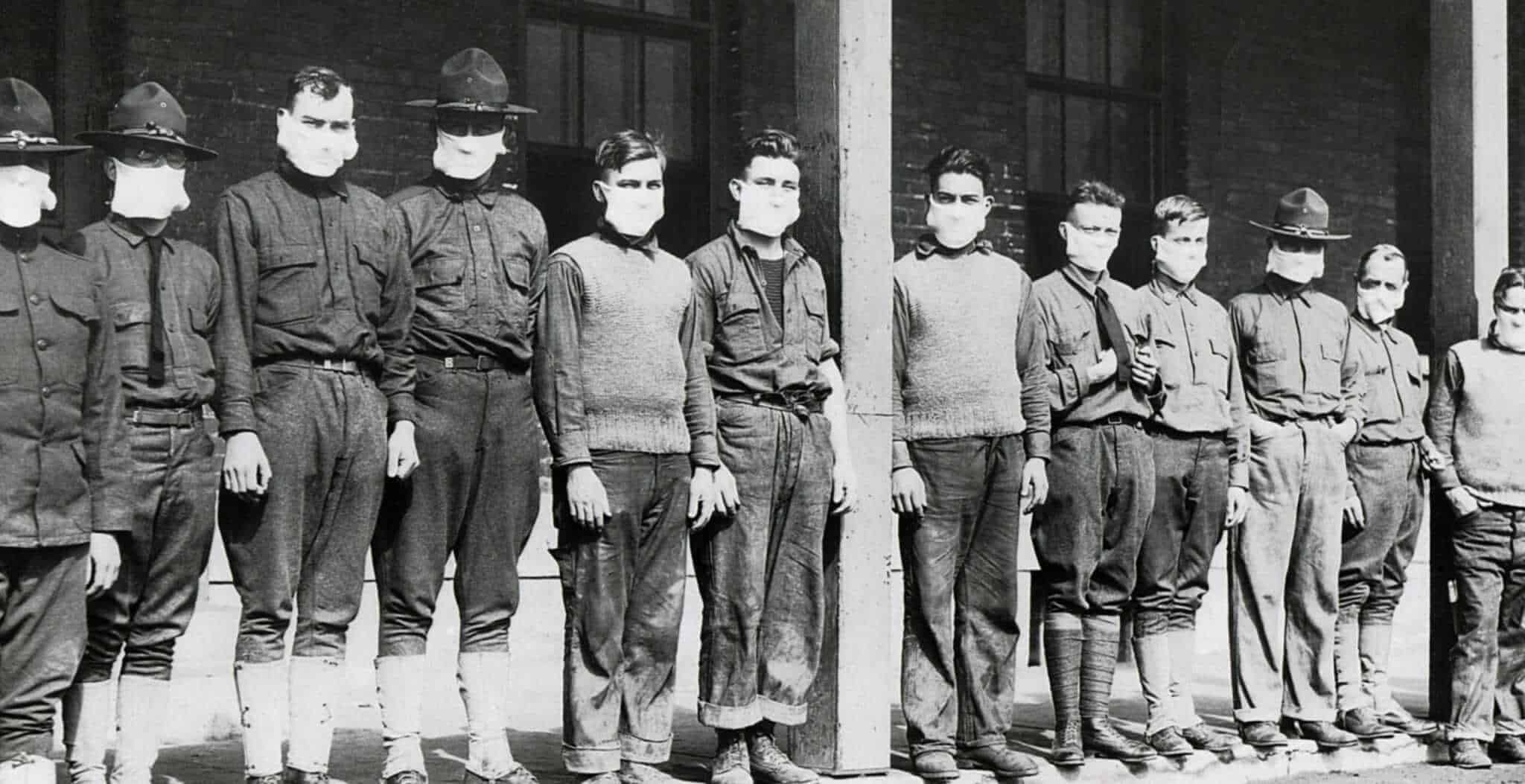

Although not caused by World War I, it is thought that in the UK, the virus was spread by soldiers returning home from the trenches in northern France. Soldiers were becoming ill with what was known as ‘la grippe’, the symptoms of which were sore throats, headaches and a loss of appetite. Although highly infectious in the cramped, primitive conditions of the trenches, recovery was usually swift and doctors at first called it “three-day fever”.

The outbreak hit the UK in a series of waves, with its peak at the end of WW1. Returning from Northern France at the end of the war, the troops travelled home by train. As they arrived at the railway stations, so the flu spread from the railway stations to the centre of the cities, then to the suburbs and out into the countryside. Not restricted to class, anyone could catch it. Prime Minister David Lloyd George contracted it but survived. Some other notable survivors included the cartoonist Walt Disney, US President Woodrow Wilson, activist Mahatma Gandhi, actress Greta Garbo, the painter Edvard Munch and Kaiser Willhelm II of Germany.

Young adults between 20 and 30 years old were particularly affected and the disease struck and progressed quickly in these cases. Onset was devastatingly quick. Those fine and healthy at breakfast could be dead by tea-time. Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of fatigue, fever and headache, some victims would rapidly develop pneumonia and start turning blue, signalling a shortage of oxygen. They would then struggle for air until they suffocated to death.

Hospitals were overwhelmed and even medical students were drafted in to help. Doctors and nurses worked to breaking point, although there was little they could do as there were no treatments for the flu and no antibiotics to treat the pneumonia.

Hospitals were overwhelmed and even medical students were drafted in to help. Doctors and nurses worked to breaking point, although there was little they could do as there were no treatments for the flu and no antibiotics to treat the pneumonia.

During the pandemic of 1918/19, over 50 million people died worldwide and a quarter of the British population were affected. The death toll was 228,000 in Britain alone. Global mortality rate is not known, but is estimated to have been between 10% to 20% of those who were infected.

More people died of influenza in that single year than in the four years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351.

By the end of pandemic, only one region in the entire world had not reported an outbreak: an isolated island called Marajo, located in Brazil’s Amazon River Delta.

It wouldn’t be until 2020 that another pandemic would sweep the world: Covid-19. Believed to have originated in the Wuhan province of China, the disease spread rapidly to all continents except Antarctica. Most governments opted for a strategy of locking down both the populous and the economy in an effort to slow the rate of infection and protect their health systems. Sweden was one country which instead opted for social distancing and hand hygiene: outcomes were at first better than some countries who had locked down for months, but as the second wave of infections hit in the early autumn of 2020, Sweden also opted for stricter local guidelines. Unlike Spanish flu where young people were most affected, Covid-19 appeared to be most deadly amongst the older population.

As with Spanish flu, no-one was exempt from the virus: the Prime Minister of the UK Boris Johnson was hospitalised with Covid-19 in April 2020 and the President of the United States of America, President Trump, suffered similarly in October.