Rows of squalid trenches in a decimated landscape of tangled mud and barbed wire, stretching interminably into the horizon. Amongst the destruction sits a man. Stricken, he wears a thousand-yard stare, his mind shattered by the living nightmare in which he has found himself. This is the image of the First World War that has been burned perhaps most indelibly into the public consciousness.

80,000 cases of shell shock – a forebear of modern Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder – were reported by the British Army between 1914 and 1918. History rightly remembers these men as victims of a culture of impossible masculinity that demanded unsustainable mental fortitude in the face of unimaginable horrors: horrors to which mental breakdown was the inevitable and only truly human response. A ‘preposterous masculine fiction,’ as Virginia Woolf christened it in 1916, the memory of the war and its most famous malady has since been dominated by men.

The cultural legacy of shell shock has reflected this preoccupation. In literature from Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway to Pat Barker’s Regeneration; in film and television from All Quiet on the Western Front to Downton Abbey, the representation of the woman’s experience marginalises them to roles as one-dimensional wives, mothers and sisters of psychologically shattered husbands, sons and brothers, suffering at the hands of the war often only by proxy.

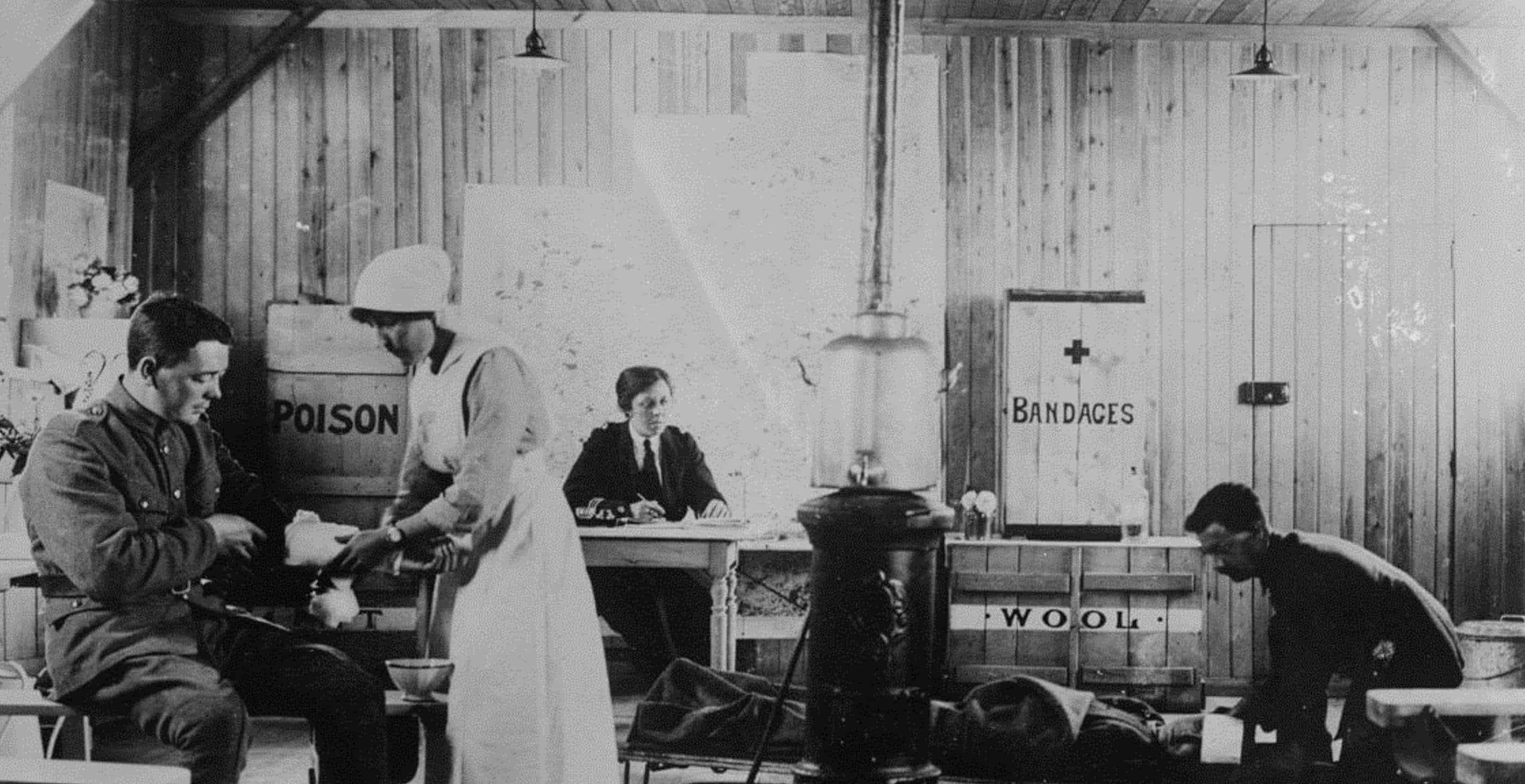

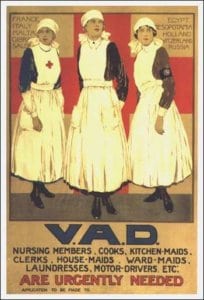

We would of course be wrong to accept this as the only possible perspective. The suffering and sacrifice of men should not be – and has not been – underestimated, but we know that, as the war raged on, women became more directly involved. As ambulance drivers, nurses and Voluntary Aid Detachments, thousands served on or near the front lines, experiencing much the same war as their male counterparts. We are approaching the 100th anniversary of the armistice, yet it was not until relatively recently that historians began to pay any real attention to the female experience of shell shock.

Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth contains her recollections of a war in which her role as a V.A.D. nurse saw her brought as close to the male soldier’s experience of the conflict as it was then possible for a woman to get. Born in 1893 to wealthy paper mill owners in Newcastle-under-Lyme, her journey to the front came via Somerville College, Oxford, where she read English Literature for a year before joining the ranks of the V.A.D. in the summer of 1915, serving in the United Kingdom, Malta and on the western front in France. She had watched as her brother Edward, fiancé Roland Leighton and close friend Victor Richardson left for the front in the year previous. By November 1918, as jubilant Armistice Day celebrations echoed around the country, all three would have perished and Brittain had experienced the fullest horrors of the war. She returned to Oxford haunted by her experiences.

Edward Brittain, Roland Leighton and Victor Richardson. Copyright of the Literary Executors for the Vera Brittain Estate, 1970 and The Vera Brittain Fonds, McMaster University Library. Licensed under the terms of the Jisc Model Licence.

Edward Brittain, Roland Leighton and Victor Richardson. Copyright of the Literary Executors for the Vera Brittain Estate, 1970 and The Vera Brittain Fonds, McMaster University Library. Licensed under the terms of the Jisc Model Licence.

Reading Testament of Youth gives a vivid sense of the consequences of Brittain’s trauma. She suffered hallucinations, delusions, nightmares, and insomnia that she attributed to ‘over-fatigue and excessive strain.’ When shell shock was being established as a diagnosis by psychologists in the first years of the war, these were among the most common symptoms presented by afflicted soldiers. ‘Had I consulted an intelligent doctor immediately after the War,’ Brittain wrote, ‘I might have been spared the exhausting battle against nervous breakdown which I waged for eighteen months. But no one, least of all myself, realised how near I had drifted to the borderland of craziness.’ Like so many returning veterans, she expressed a feeling of profound alienation in the aftermath of war, where ‘never again, for me and for my generation, was there to be any festival the joy of which no cloud would darken and no remembrance invalidate.’

As fascinating as Brittain’s story is, she must be remembered as a symbol of women’s psychological sacrifice, not the aberration that much of the historical literature on shell shock would have us believe. The lack of wartime examples of women being treated for the condition speaks not to a lack of trauma, but to an inherent prejudice that placed the male soldier’s suffering – and the need to return them to fighting fitness – above all else. Although the term ‘civilian war neuroses’ came into use to recognise the mental toll taken by the war on those in non-combatant roles, it was always a distinct diagnosis used to separate the men from the rest.

Yet they were not so separate. In fact, Brittain was a woman in a man’s world in both peace and war. At Somerville, one of the first women’s colleges, she was in the female minority of the then male-dominated world of higher education. So, too, with her sisters–in-arms at the front. The men were required to show unrealistically stiff upper lips in the face of abject fear; it makes little sense to assume that the women of the front would not also have to perform similar mental acrobatics in order to survive. When this impossible standard was not met, why would their mental breakdown be any different? Brittain revisited the battlefields of France several times in the years following the war. She writes:

‘The main railway line from Boulogne to Paris ran between the hospitals and the distant sea, and amongst the camps … To-day, when I go on holiday along this railway line, I have to look carefully for the place in which I once lived so intensely. After a dozen almost yearly journeys, I am not sure that I could find it, for the last of the scars has disappeared from the fields where the camps were spread; the turnips and potatoes and mangel-wurzels of a mild agricultural country cover the soil that held so much agony.’

While the battlefields may have rapidly disappeared, let’s not let our memory of the women who endured their horrors suffer the same fate. Brittain, and the thousands of women who suffered silently

beside her, must occupy a place alongside the men in our remembrance of the war this November.

Jobe Close is a freelance writer specialising in history and film.