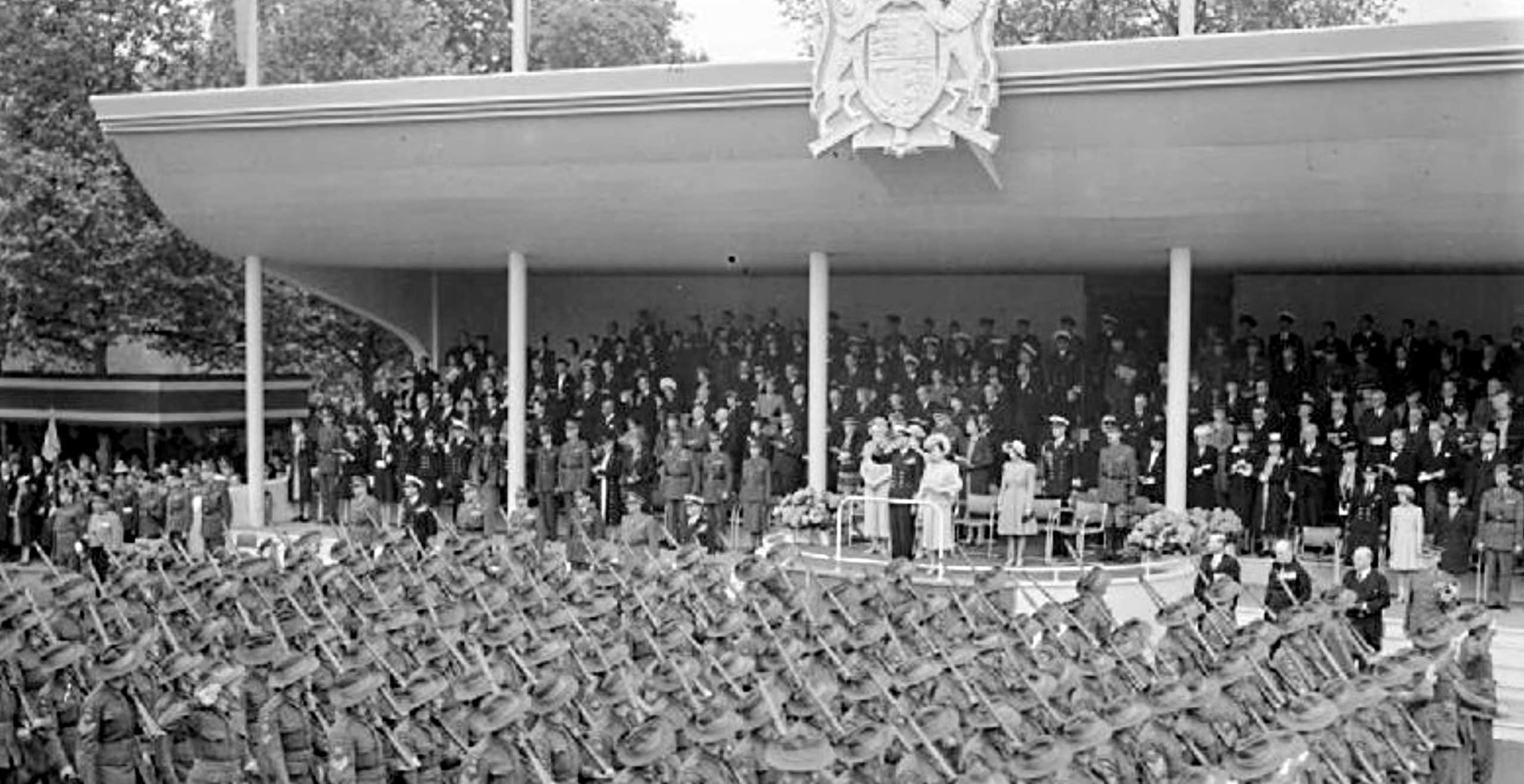

On 8th June 75 years ago thousands of people lined London’s streets to see the triumphant Victory Parade celebrating the end of World War 2, and I was among them with my parents and younger brother.

We had arrived by train from Gillingham the day before and stayed overnight with an aunt in Putney, rising early next morning to travel on the Underground to a favoured spot in Parliament Square opposite Westminster Abbey and Big Ben. People were standing 10-deep by the time the parade began so children were moved to the front and saw everything.

Leading the parade were the famous military commanders we had read about in the newspapers and seen in newsreels, including Generals Montgomery, Eisenhower and Smuts, all listed in the official programme I have among my souvenirs.

Behind them came more than 500 vehicles of the Allied armed forces, tanks, Bren-gun carriers and other self-propelled weaponry; uniformed marching columns of British, Commonwealth, United States and foreign men and women of the navy, army and air forces; Indians and Gurkhas, men and women from South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and the female forces of the W.R.E.Ns (Navy), W.A.A.Fs (Air Force), W.A.A.Cs (Army) and the W.L.A. (Women’s Land Army).

Above us, an aerial parade featured a fly-past of 300 fighter planes and bombers, and the gliders that carried paratroopers in the D-Day invasion of Europe that hastened the end of Nazism.

After sunset, London’s main buildings were lit up by floodlights and crowds thronged the banks of the Thames to see King George VI and his family sail past in the royal barge. The festivities ended with a gigantic fireworks display over Central London.

As I was 14-years-old in 1946 my memories of that amazing day are still vivid – and just as amazing is the fact that all four members of the Jones family survived the war unscathed.

Richard aged 14 in 1946

Richard aged 14 in 1946

I also clearly recall a Sunday in September 1939 when I was seven years old and my brother, Evan, was two. My mother had taken us to visit my widowed grandmother in Grimsby, Lincolnshire, and as we sat down for dinner we heard BBC news reader Alvar Liddell (unusual name) solemnly announce that Adolf Hitler’s army had invaded Poland and Britain was now at war with Germany.

Two little patriots: Richard (right) and brother Evan

Two little patriots: Richard (right) and brother Evan

We lived in the Medway River town of Gillingham, Kent, and when the forces of Nazi Germany prepared to invade England In 1940, the Luftwaffe began intensive and prolonged aerial attacks (The Blitzkrieg) to soften us up. The bombing of London (only 30 miles from us) and Kent became so intense that my mother put the furniture into storage and we left Gillingham to live with my grandmother for almost a year.

When the bombing eased off in 1941 we returned to Gillingham and had a huge hole dug in the back garden and an Anderson air raid shelter was installed. It was about eight feet deep with a corrugated iron roof, over which soil from the hole was compacted and then grass sods were planted on top. Inside were four bunks on which we slept (or tried to sleep) during air raids. Although rather damp inside, it was supposed to be safer than staying in the house.

As we were so close to London, German aircraft would drop bombs on us if they failed to reach the capital city. Chatham’s naval base and dockyard were also prime targets, as well as the Short’s factory at nearby Rochester where Sunderland flying boats were made. Gillingham was only a few miles away from both neighbouring towns.

Our school time was often interrupted by air raids. For instance, if the air raid warning siren sounded before children left for school they would have to stay at home until the “All Clear” sounded.

All schoolchildren were issued with gas masks when the war began as the British Government feared that the Germans would use poisonous gas on the population, as they had done against Allied troops in World War I. We took the gas masks to school in a shoulder bag and were instructed about how to wear them in an emergency, but thankfully they were never needed.

Every night, all over England, there would be a full black-out so that German aircraft couldn’t identify the towns below and drop their bombs. “Black-out” meant that street lights were switched off and lights in houses and buildings had to be completely shielded from above. If there was the slightest chink in your black curtains an air raid warden would knock on the door and shout: “Put that bloody light out!” It was a very serious offence to show a light because it could endanger everyone in town.

Richard’s father, Fred Jones

Richard’s father, Fred Jones

When the war began in 1939 my father was a Chief Petty Officer gunner’s mate on the 32 000-ton battleship HMS Warspite, which was immediately ordered into action. He was the captain of “B” Turret with its two 15-inch guns and crew of 70. We did not to see him again until October 1941 after Warspite was badly damaged by a 500lb bomb in an aerial attack off the island of Crete in the Mediterranean, and the crew were transferred to other ships or shore establishments while the ship was repaired in the USA.

I was taken aback upon leaving home one morning to walk to school when a Heinkel bomber roared into sight immediately above me, flying towards the Medway River. When I turned to follow its flight path I spotted the aircraft’s rear gunner staring down with his hands on the machine-gun – and then the plane disappeared into the distance. Whether it reached Germany or crashed on the way will forever remain a mystery.

A V1 bomb nicknamed a Doodle-bug

A V1 bomb nicknamed a Doodle-bug

Towards the war’s end in June 1944 the Germans began sending over V1 pilot-less flying bombs we nick-named Doodlebugs or Buzz-bombs. They could be seen with flames spurting from their engines and when they ran out of fuel they would plummet down – and 1 000lb of explosives destroyed everything where they landed.

It was fascinating to watch daring RAF pilots fly their Spitfires and Hurricanes alongside the V1s to tip their wings, turning them completely around until they were flying back towards the English Channel, where they exploded harmlessly in the sea.

The Joneses had a close call with a Doodlebug one day when Evan and I were in the back garden helping mother hang out the washing. A flying bomb had appeared about 1 000 ft. above us when the engine suddenly went “putter-putter” and stopped. The three of us were about to dive into the shelter when it dipped into a glide path and exploded in the river mud about a kilometre away.

In September 1944 the Germans launched the V2 rocket offensive at south-east England. This weapon was more like a modern missile and was a much larger bomb than a Doodlebug. It couldn’t be seen until it landed with a loud “whoomf” and exploded, so there was very little chance of surviving. Two of my school friends were having dinner one Sunday when a V2 struck a house a couple of doors away and killed all the occupants.

After the war I saw a map of the Medway towns with pins marking all the places where V1s and V2s had fallen. It was literally covered in pins, so we considered ourselves very fortunate to have escaped death or having our house destroyed. More than 100 of these bombs were launched at us every day (a total of 90,521), killing 6,184 people and injuring 18,000. About 4,600 V1s were destroyed by British fighters, anti-aircraft fire and barrage balloons before they reached their targets and the attacks ended only when the invading Allies over-ran the launch sites in France.

On 6 June 1944, when the Allies launched the D-Day landings, we did not go to school because an aerial armada flew over us en route to France. They were so low that the noise from their engines was deafening. DC3 Dakotas were pulling Horsa gliders filled with troops, and the larger R.A.F. Wellington and Bristol Blenheim bombers and American Super-Fortresses were towing bigger Horsa gliders carrying jeeps and other heavy equipment.

A year later the war in Europe was over and we hung a big Union Flag out of the upstairs front window of our house at 60 King Edward Road. Victory in Europe Day (8 May 1945) prompted celebrations all over Britain, with people dancing and singing in the streets, and ours was no exception. Trestle tables were set up and neighbours contributed eats and drinks for one huge party. And exactly a year afterwards, the Jones family were in London to witness the grand Victory Parade.

The Victory Parade

The Victory Parade

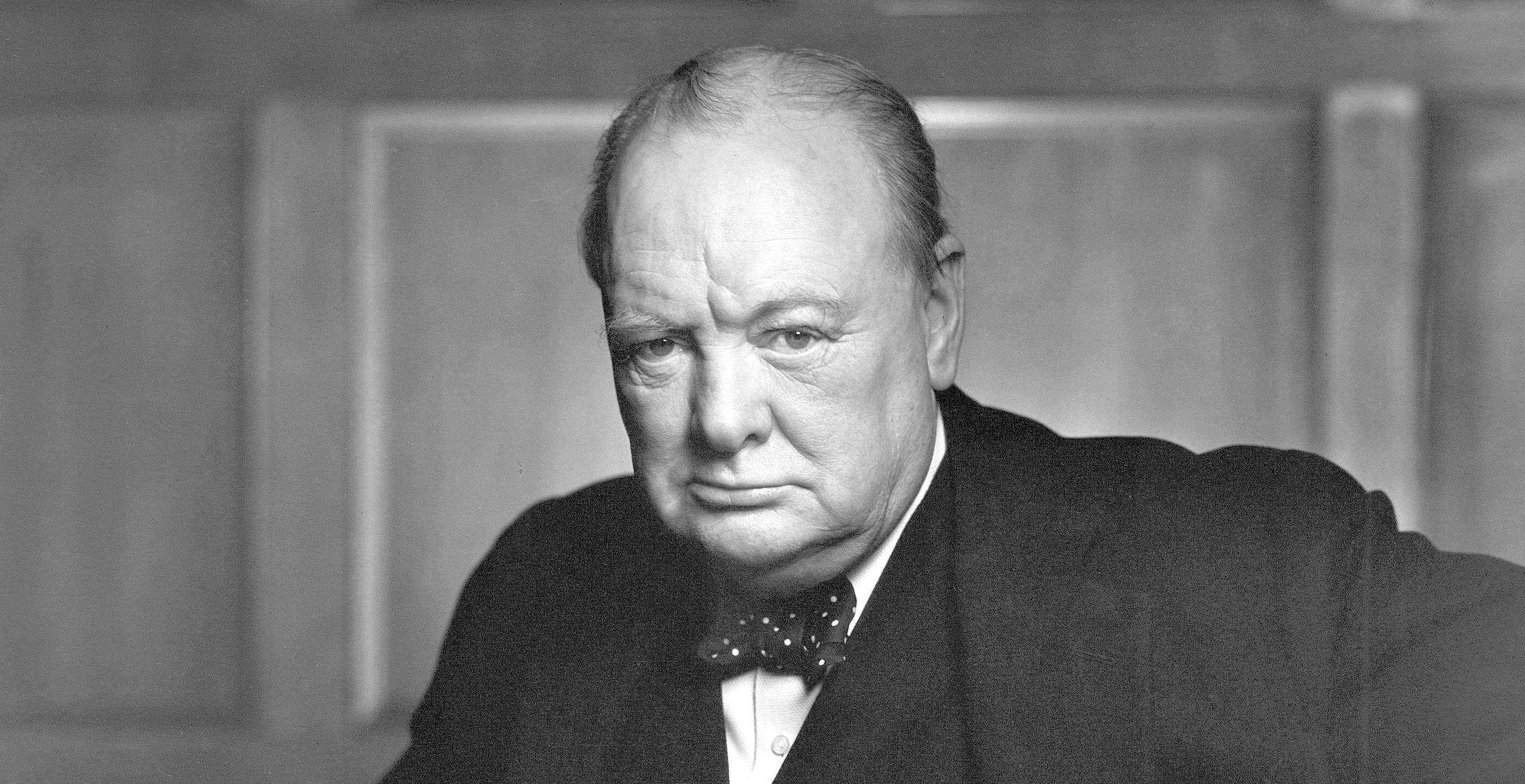

In later life, I crossed the English Channel on a hovercraft from Dover to Boulogne and realised how fortunate the British were to have that 20-mile stretch of water between them and France. It was also fortunate that Winston Churchill was the Prime Minister at the time, for his wartime rallying speeches gave everyone the will to win the war.

My father was extremely upset when, in the first post-war general election, Britain’s electorate dumped Churchill in favour of a Labour Government led by Clement Attlee, who immediately introduced austerity measures. However, Dad was secretly pleased about his decision to start a new life in South Africa because, unknown to his sons, he had successfully applied for a post as gunnery officer with the expanding South African Navy.

Our ship, the SS Georgic, sailed from Liverpool at 11 p.m. on 28 December 1946, taking the Jones family to Durban from their country of birth, never to live there again.

Richard (Dick) Jones was night editor of South Africa’s oldest daily newspaper “The Natal Witness” from 1967 to 1974 before serving in the tourism sector for 44 years. His historical novel “Make the Angels Weep – South Africa 1958” is available as an e-book on Amazon Kindle

The author aged 89 in 2021

The author aged 89 in 2021