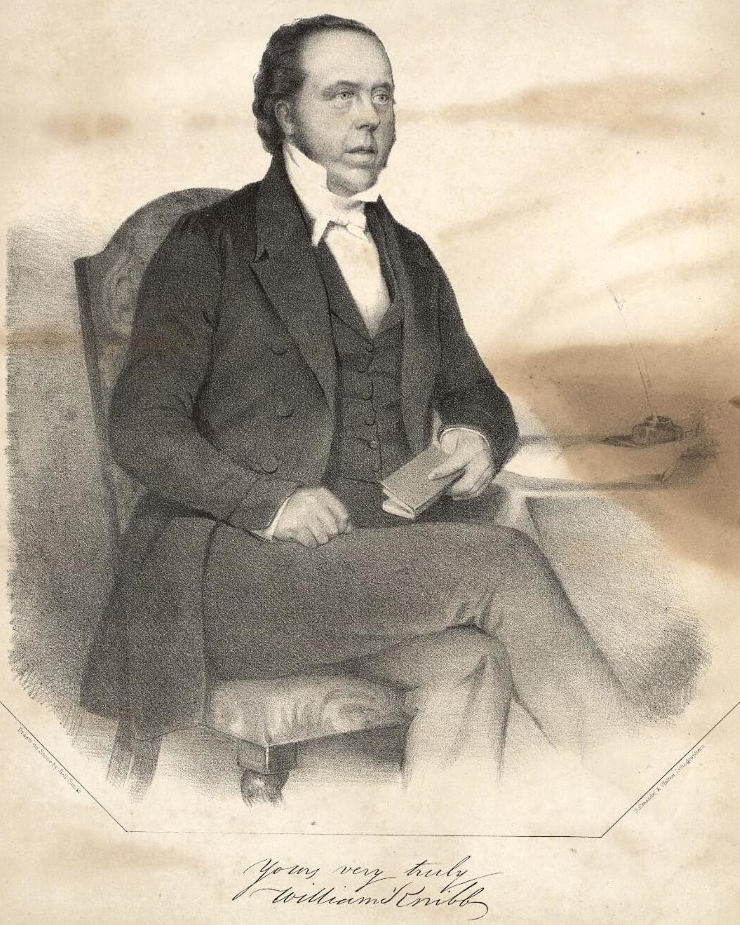

“The cursed blast of slavery has, like a pestilence, withered almost every moral bloom”.

The words of William Knibb, an English Baptist Minister who began his life in Northamptonshire but would make his mark in Jamaica as an individual who thought the abhorrent practices of slavery must come to an end.

Born in Kettering in 1803 to a large family of eight children, William Knibb began his career as an apprentice to a printer in Bristol. When he was still in his youth Knibb had become a Baptist and looked set to follow in his brother’s footsteps when his older brother Thomas began work as a school teacher in Jamaica.

Sadly, only a year into his missionary activity, his brother Thomas passed away and William took the opportunity to offer to fill his place, attending a college in 1824 in order to prepare him for life as a teacher.

By November the same year William, accompanied by his wife Mary, took the long journey to Jamaica, arriving three months later.

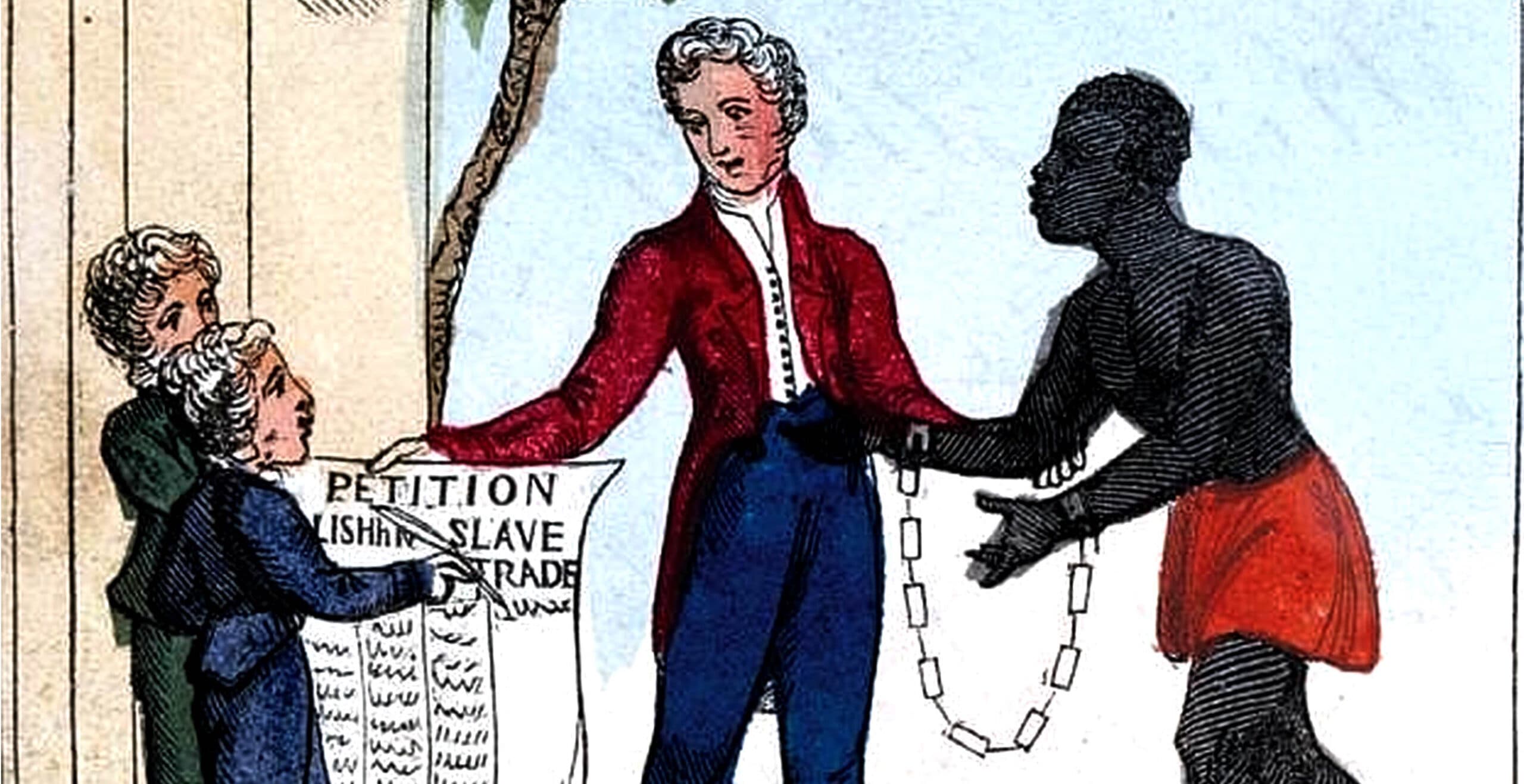

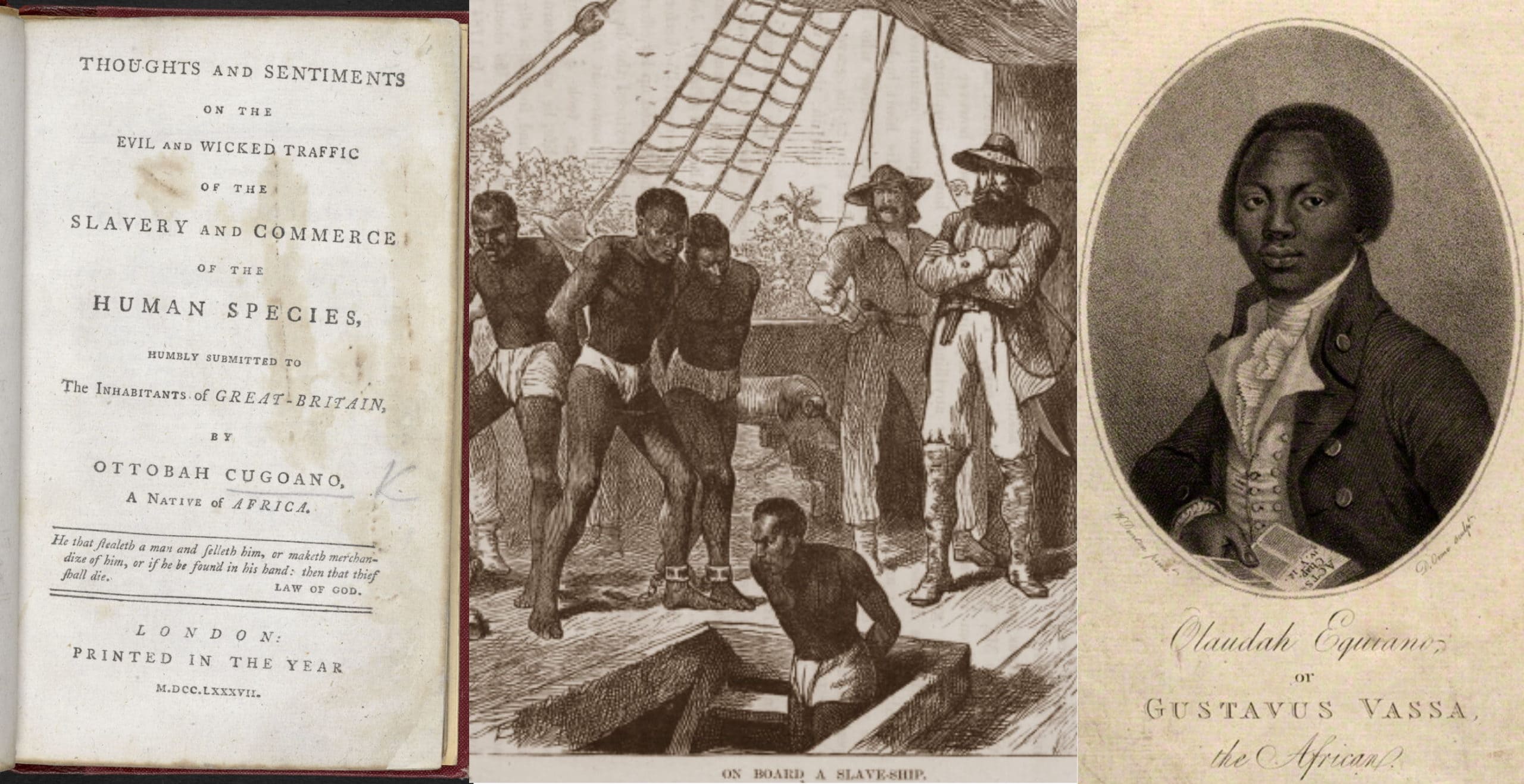

As soon as he arrived, Knibb was struck by the endemic slavery pervading the island, exposing all the horrors and harsh realities such a practice brought with it. At the time slavery was still legal whilst the international slave trade itself had been formally abolished in 1807 (excluding possessions of the East India Company, Ceylon and Saint Helena), with the likes of William Wilberforce and his compatriots fighting for the cause back in Britain.

Meanwhile, for those suffering the physical and mental shackles of this system, slavery still existed as the law did not abolish the practice so much as the trade.

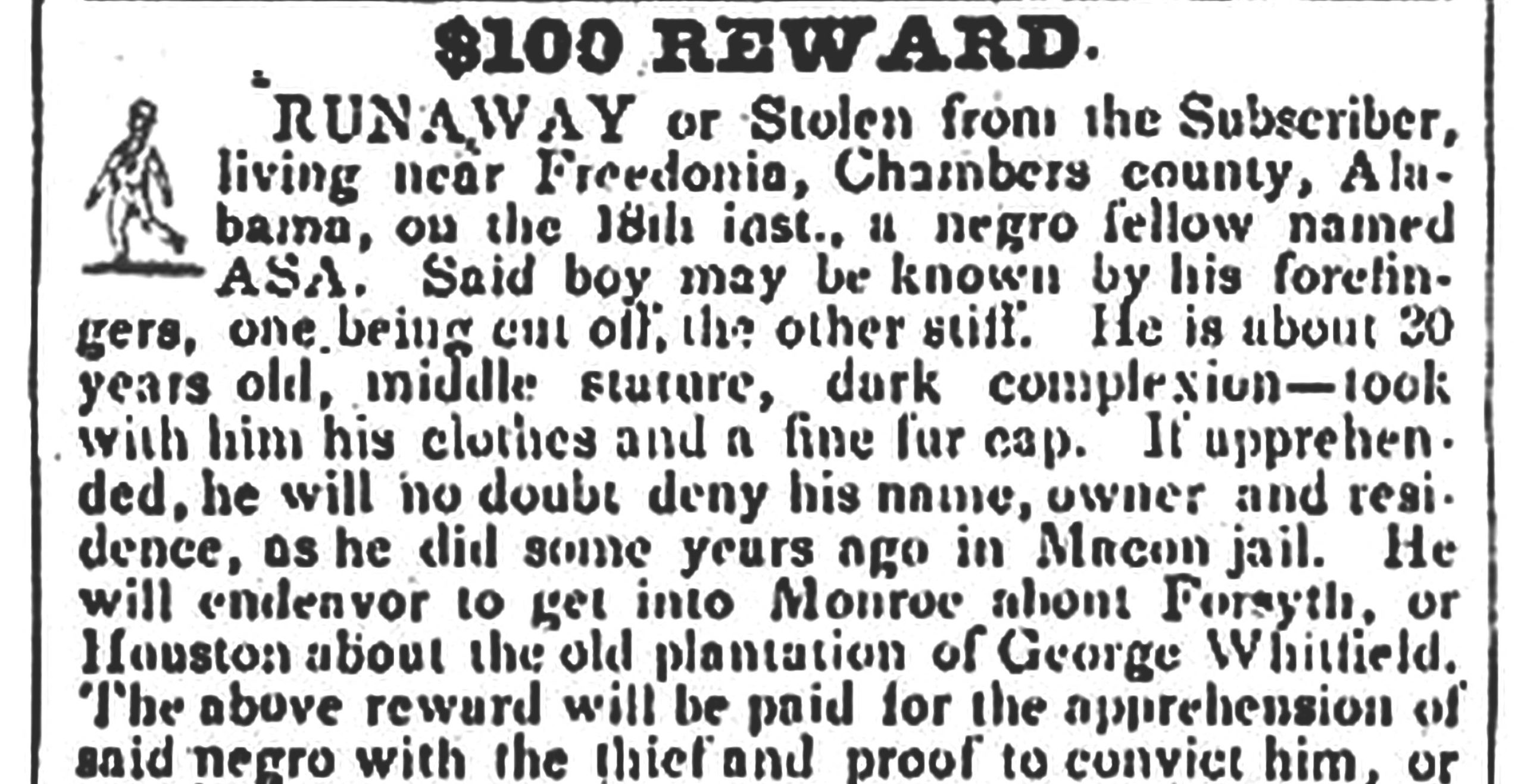

Treatment was sickeningly harsh and punishment severe for the most minor incidences. Floggings were commonplace in the midst of back-breaking work, repulsing William who bore witness to the conditions.

Back at the school, Knibb felt the existing school was insufficient and set to work in and instigated a new school to be built in Kingston. This quickly grew in capacity to accommodate more than 200 pupils, comprising a combination of free and enslaved individuals.

Knibb continued his missionary work, dedicating himself to providing an education for his students, teaching six out of seven days as well as providing an additional Sunday School for adults and children alike.

After spending his initial time in Kingston, as a result of his health he later moved to Port Royal and in 1828 settled in Savannah-la-Mar. It was in Savannah-la-Mar that a man named Sam Swiney, a deacon at the church and also a slave, chose to organise prayer meetings at his house.

This innocuous act quickly gained the attentions of the local law enforcement who gave him a sentence of twenty lashings as well as working on the road for two weeks for the crime of preaching without a licence.

Despite the fact that three other witnesses could corroborate that he had arranged prayers not preaching, his sentence was carried out nonetheless.

Upon hearing the news of this man, Knibb accompanied him to the flogging and walked beside him as he completed his work on the roads in shackles as a sign of loyalty and support to a man whose only crime was to pray.

In the eyes of Knibb, such a horrific injustice needed to be made public and he contacted press in both Jamaica and England in order to inform more people about the situations occurring on a daily basis.

As a result of the publication of Swiney’s fate, back in England a church helped to acquire Swiney’s freedom sending a correspondence to the Governor of Jamaica, highlighting the miscarriages of justice committed in his name. Once the Governor was made aware of his case, he responded by sacking the magistrates who had passed this sentence.

Change was afoot but in the meantime many continued to suffer in silence.

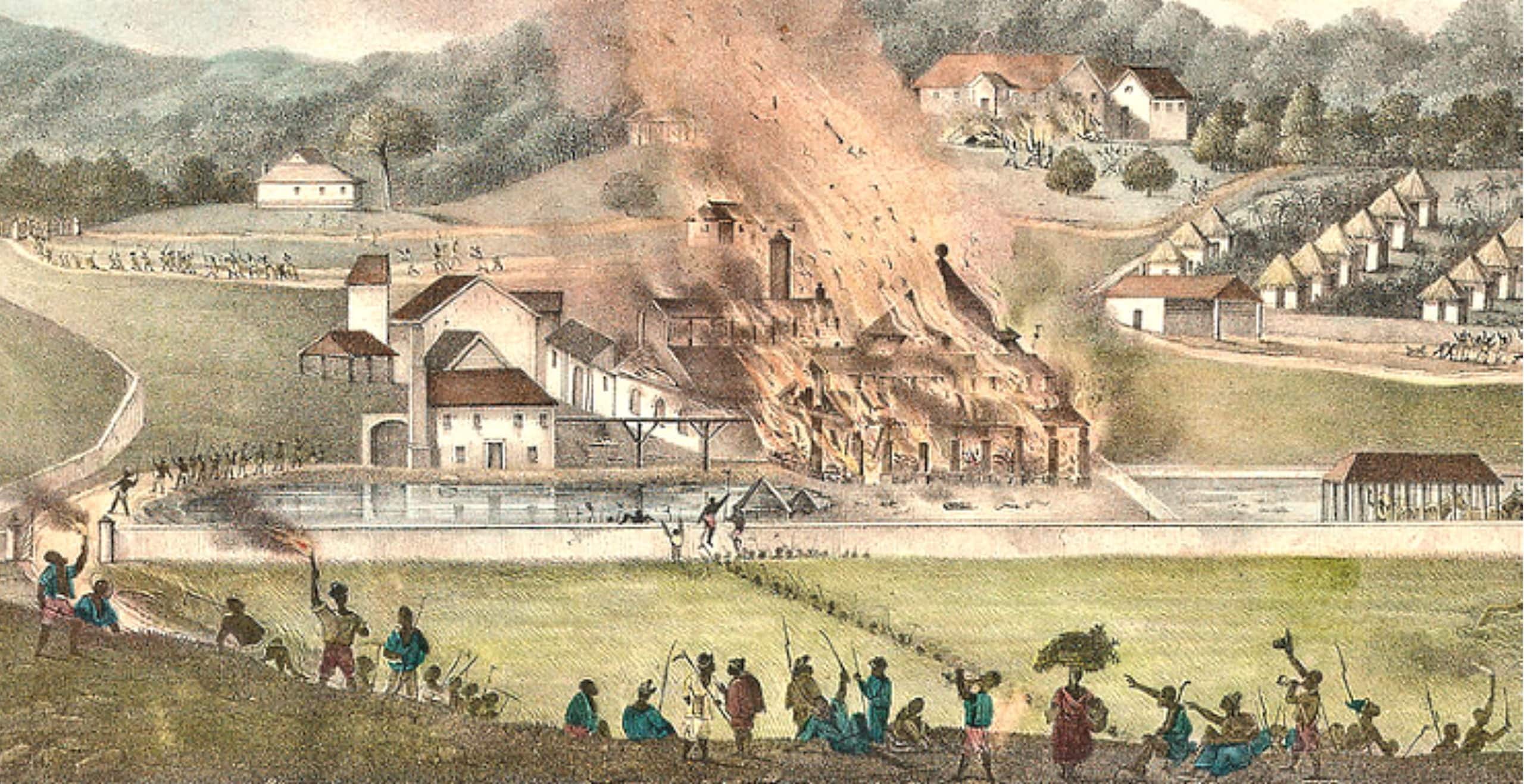

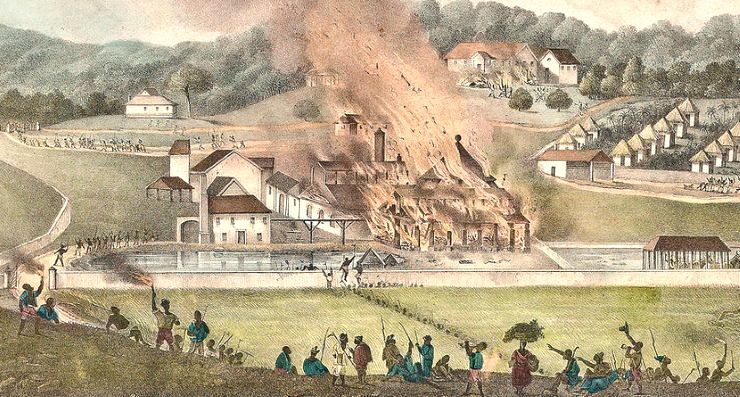

By 1830 Knibb was serving at Falmouth Baptist Church which had a large congregation of more than 500. It was at this location that an historic rebellion broke out in December the following year, initiated by a slave and deacon called Sam Sharpe who organised a protest and strike.

The event unfortunately soon escalated into a violent collision course between the army who wanted to quell any signs of rebellion and the slaves who wanted their voices heard. What would be later referred to as the Baptist War or Christmas Rebellion was suppressed by the army and led to Samuel Sharpe meeting his fate at the gallows in 1832.

Whilst the Baptist Samuel Sharpe had organised this rebellion in western Jamaica, Knibb soon found himself in the crossfire, accused by the plantation owners of inciting and encouraging this uprising, whilst in reality Knibb had only found out about the plans two days previously.

His pleas for mercy fell on deaf ears as he was later arrested for complicity and taken to court where a number of witnesses were called upon giving false information about his involvement. Despite the odds stacked against him, Knibb managed to get bail but his ordeal was far from over.

His anti-slavery rhetoric was in direction opposition to the colonial authorities who began to view him as a trouble-maker, guilty of supporting insurrections which threatened their livelihood.

Knibb and missionaries such as him were viewed as problematic by the colonial officials and plantation owners, forcing even more violent reactions.

One particular individual involved was an Anglican clergyman by the name of Bridges who founded the Colonial Church Union. This association was effectively in opposition to those who wanted to end the practices of slavery and used a number of violent and illegal tactics to drive out the Baptists who they saw as instigators for this revolutionary zeal embodied by the slaves.

Sadly, as so much was at stake for the plantation owners, scenes turned even uglier with anti-abolitionists choosing to burn down several chapels that were frequented by their slaves, including Knibb’s church at Falmouth. Many churches were lost at this time.

The violence did not stop there. Knibb soon found himself a main target of the owners who were determined to force him to leave the island. For many missionaries like him, the choice was simple, to leave Jamaica for their own safety but Knibb was determined not to be forced out.

As a result Knibb found himself at the epicentre of attacks with an armed mob targeting his home, resulting in his entire family forced to find safety elsewhere, with only a few sympathetic to his predicament. For several weeks his new base was on a ship in Montegro Bay, in protective custody, such was the threat to his life.

In the end, for his own safety and as a means of continuing to spread the message of abolition, Knibb returned to England in order to engage the public back home.

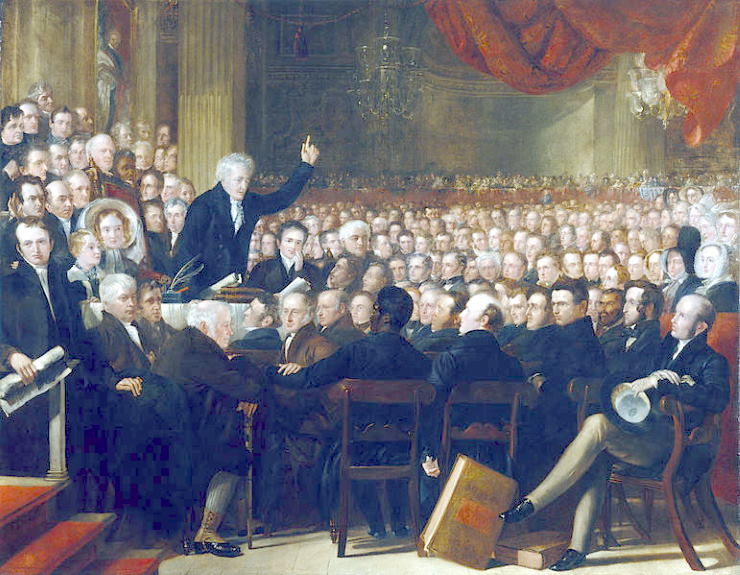

In 1832, Knibb embarked on a tour of England and Scotland, reporting the incidences he had incurred in Jamaica, relaying the work of the nonconformist churches and highlighting the treatment of slaves.

With much success, his compelling arguments instigated the Baptist Missionary Society to outwardly speak out against slavery and garnered increasing numbers of support in key areas. One of these areas included parliament itself where Knibb had been summoned in order to give evidence to a committee who had been investigating the practices in the colonies.

His message was finally being heard by the wider public as well as those in key decision-making positions, so much so that in 1833 the following year, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed.

The act received its third reading in parliament only three days before the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce passed away. It officially came into force in August the following year with the inclusion that any slave below the age of six were free in the colonies, whilst anyone over the age received the status of “apprentice”.

This proviso meant that the process of ending slavery was drawn out over several years with apprenticeships scheduled to end in 1840. The result was that slavery had been replaced by apprenticeships which required the individuals to work for their masters free of charge for another six years. Unsurprisingly, the system of transition was badly abused by the plantation owners.

Knibb had been unsatisfied with the details of the act, forcing “apprenticeships” on the slaves, under the guise of freedom. He remained resolute and continued to campaign, sadly resulting only in a reduction of service from six years to four years for the apprentices.

In the meantime, another stipulation of the Act also resulted in slave-owners being compensated for their lack of revenue.

Eventually in 1838 the apprenticeship scheme was abolished. Knibb chose to mark this occasion by burying chains and shackles in a coffin, with the sign reading:

‘Colonial slavery died 31 July 1838, Age 276 Years.’

Meanwhile, as a result of the Act and the steps that followed, William Knibb found himself returning to Jamaica once more, this time, with a sizeable donation to provide the means to rebuild the churches which had been destroyed by the plantation owner’s rampage.

The money also helped in the provision of general infrastructure on the island with new schools opening up, including one in Falmouth run by Knibb himself.

He continued his good work in Jamaica, setting up a Free Village scheme in order to house former slaves. Moreover, the church saw an upswing in conversions, with congregations greatly enlarged as many of the individuals had previously been hindered from attending. This religious revival soon became known as the Jamaican Awakening, as emancipation and faith went hand in hand.

His dedication to the cause would continue until his death in November 1846 as he passed away at the age of forty-two from yellow fever in Falmouth, Jamaica.

In 1998, his efforts were recognised by the Jamaican Order of Merit, the highest honour for civilians.

His legacy, like many others like him, of all colours and creeds, marked an important stepping stone in the fight for equality and humanity.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.