The First World War was a total war, in that those on the Home Front were not isolated from the fighting on the battlefields, but instead were as crucial to victory or defeat as the soldiers in the army, the aviators or the sailors in the navy.

The two pillars upon which Britain’s war effort rested were industry and agriculture. Industry produced the munitions to fight the war whilst agriculture was vital to produce enough food to fend off starvation as the U boats took their toll on imports. While the men were away fighting in the armed forces, women provided the manpower to keep both agriculture and industry going.

As well as the more traditional roles of nursing and caring, women were employed in the factories (in particular munitions factories) and on the farms, buses, trams and trains. All these sectors were essential for victory in the war.

Mining was also an essential occupation. To begin with, miners were discouraged or banned from joining up as coal was vital to the war effort, but as the fighting in the trenches reached stalemate, miners were drafted in to lay land mines and dig tunnels. Tunnelling was a very dangerous occupation as there was a constant danger of poisonous gas, cave-ins and detection by the enemy.

The Germans were vastly superior in early mine warfare and to combat this threat, it was decided to recruit experienced miners to form tunnelling companies within the Royal Engineers. Sir John Norton-Griffiths, an MP and engineer with his own civil engineering company, was tasked with recruiting trained miners: indeed the first 30 or so miners were from his own company in Liverpool.

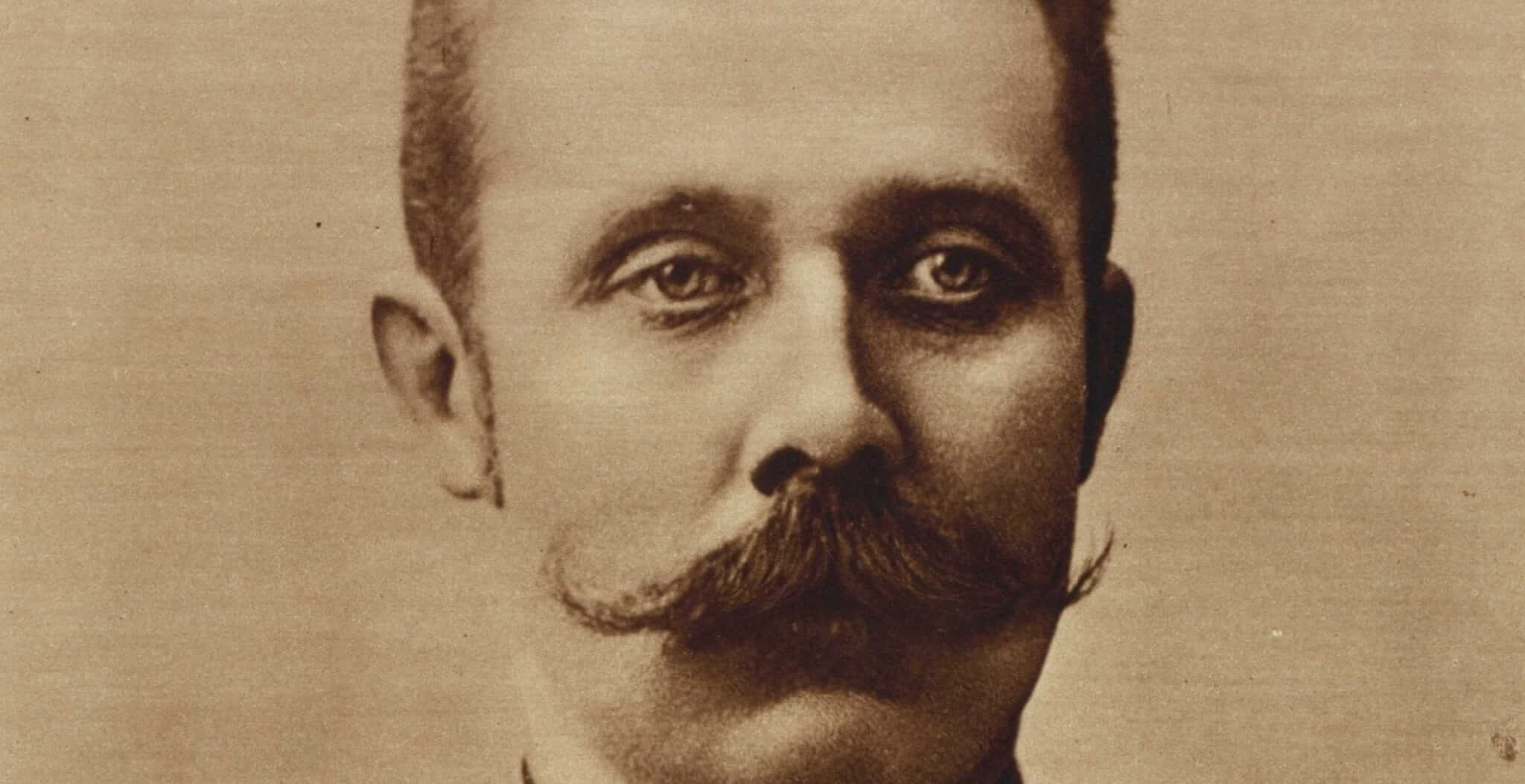

Sir John Norton-Griffiths

Searching for experienced miners already in the army, Norton-Griffiths would drive his Rolls Royce (named Gwladys after his wife) from battalion to battalion, its trunk laden with fine wines which he would share with the battalion officers before recruiting any experienced miners from those battalions. Despite Norton-Griffiths efforts, there were just not enough enlisted miners and civilian miners had to be recruited. By the end of 1915, the British were tunnelling more efficiently than the Germans.

By October 1916, coal was in such short supply in Britain that it was rationed according to the number of rooms in a house. Conscientious objectors were drafted in as miners towards the end of the war to maintain the supply of coal.

Unskilled agricultural workers were particularly liable to be conscripted and this caused much resentment among the farming community. Farm labour was also critical to the war effort, especially later when the U-boat blockade meant that more and more food had to be produced. Farmers complained that if ploughmen or blacksmiths were taken into the army, they were not easily replaced and this would actually hinder the war effort.

In an effort to overcome the lack of farm labour and the threat of food shortages, the Women’s Land Army was set up. Over 260,000 women were employed as farm labourers to replace the men sent to the Front.

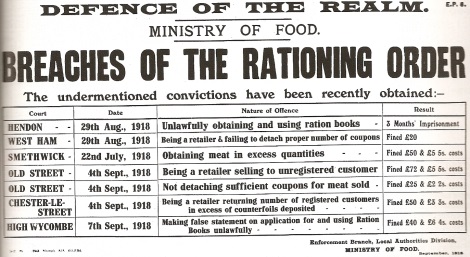

Despite these measures, food supplies were stretched and in 1917 the government introduced a voluntary code of rationing whereby people limited themselves to what they should eat. The guide was no more than two courses for lunch and three for supper if dining in a public place.

However more radical measures were needed as food supplies were now being seriously depleted as a result of the German U-boat blockade. In January 1918, sugar was rationed and by the end of April meat, butter, cheese and margarine were also rationed. Thanks in part to a good wheat harvest in 1918 and the U-boat threat being contained through the convoy system, the food crisis was averted. Sugar and butter however remained on ration until 1920.