Long before the birth of Christ, midwinter had always been a time for merry making by the masses. The root of the midwinter rituals was the winter solstice – the shortest day – which falls on 21st December. After this date the days lengthened and the return of spring, the season of life, was eagerly anticipated. It was therefore a time to celebrate both the end of the autumn sowing and the fact that the ‘life giving’ sun had not deserted them. Bonfires were lit to help strengthen the ‘Unconquered Sun’.

For Christians the world over this period celebrates the story of the birth of Jesus, in a manger, in Bethlehem. The scriptures however make no mention as to the time of year yet alone the actual date of the nativity. Even our current calendar which supposedly calculates the years from the birth of Christ, was drawn up in the sixth century by Dionysius, an ‘innumerate’ Italian monk to correspond with a Roman Festival.

Until the 4th century Christmas could be celebrated throughout Europe anywhere between early January through to late September. It was Pope Julius I who happened upon the bright idea of adopting 25th December as the actual date of the Nativity. The choice appears both logical and shrewd – blurring religion with existing feast days and celebrations. Any merrymaking could now be attributed to the birth of Christ rather than any ancient pagan ritual.

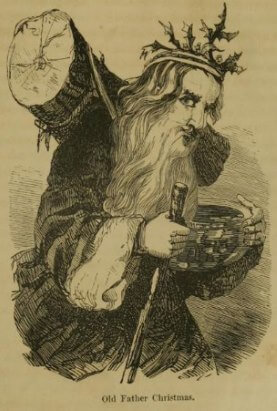

One such blurring may involve the Feast of Fools, presided over by the Lord of Misrule. The feast was an unruly event, involving much drinking, revelry and role reversal. The Lord of Misrule, normally a commoner with a reputation of knowing how to enjoy himself, was selected to direct the entertainment. The festival is thought to have originated from the benevolent Roman masters who allowed their servants to be the boss for a while.

The Church entered the act by allowing a choirboy, elected by his peers, to be a Bishop during the period starting with St. Nicholas Day (6th December) until Holy Innocents Day (28th December). Within the period the chosen boy, symbolising the lowliest authority, would dress in full Bishop’s regalia and conduct the Church services. Many of the great cathedrals adopted this custom including York, Winchester, Salisbury Canterbury and Westminster. Henry VIII abolished Boy Bishops however a few churches, including Hereford and Salisbury Cathedrals, continue the practice today.

Traditionally, a large log would be selected in the forest on Christmas Eve, decorated with ribbons, dragged home and laid upon the hearth. After lighting it was kept burning throughout the twelve days of Christmas. It was considered lucky to keep some of the charred remains to kindle the log of the following year.

Whether the word carol comes from the Latin caraula or the French carole, its original meaning is the same – a dance with a song. The dance element appears to have disappeared over the centuries but the song was used to convey stories, normally that of the Nativity. The earliest recorded published collection of carols is in 1521, by Wynken de Worde which includes the Boars Head Carol.

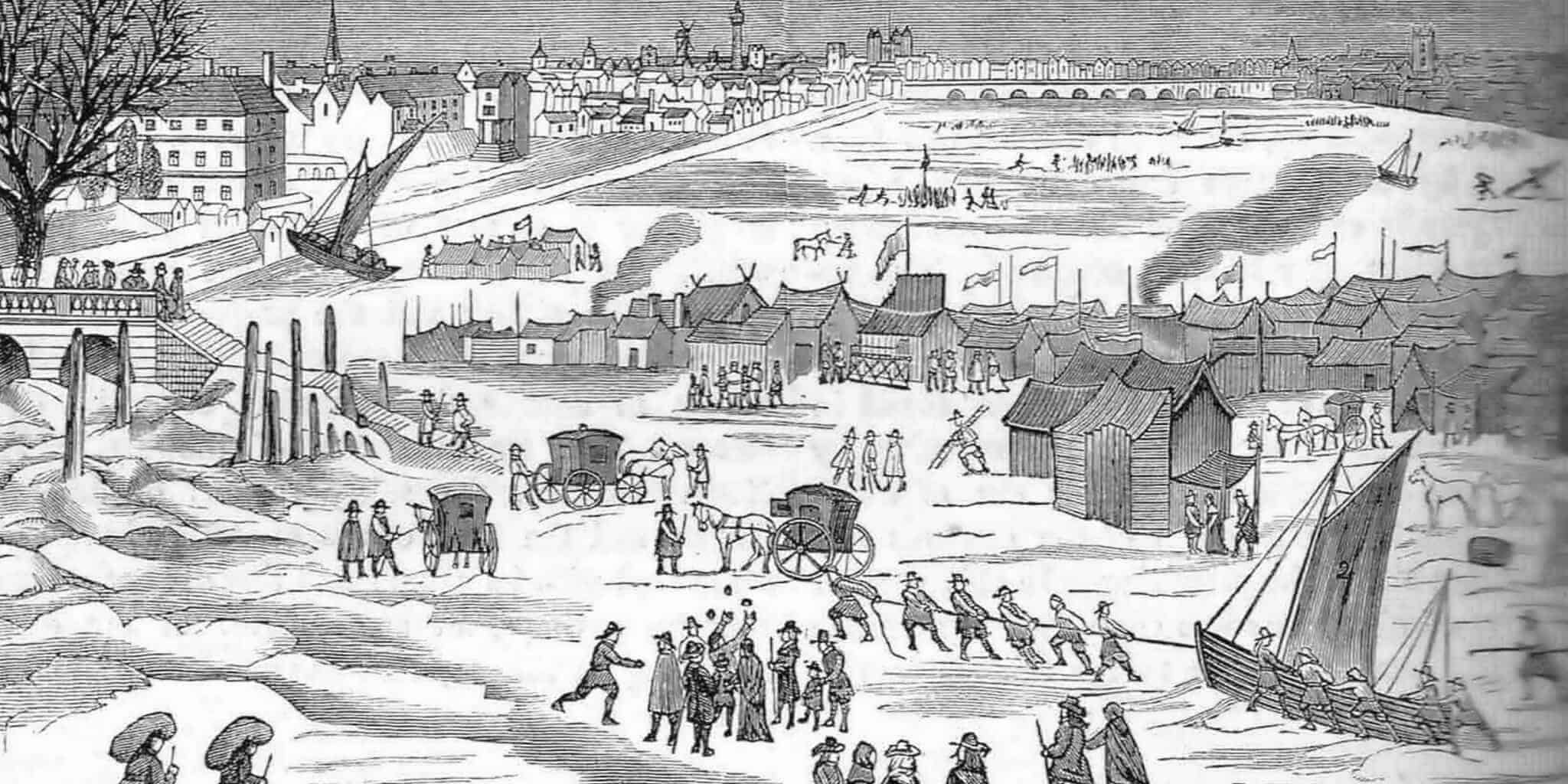

The twelve days of Christmas would have been a most welcome break for the workers on the land, which in Tudor times would have been the majority of the people. All work, except for looking after the animals, would stop, restarting again on Plough Monday, the first Monday after Twelfth Night.

The ‘Twelfths’ had strict rules, one of which banned spinning, the prime occupation for women. Flowers were ceremonially placed upon and around the wheels to prevent their use.

During the Twelve Days, people would visit their neighbours sharing and enjoying the traditional ‘minced pye‘. The pyes would have included thirteen ingredients, representing Christ and his apostles, typically dried fruits, spices and of course a little chopped mutton – in remembrance of the shepherds.

A Tudor Christmas Pie was indeed a sight to behold but not one to be enjoyed by a vegetarian. The contents of this dish consisted of a Turkey stuffed with a goose stuffed with a chicken stuffed with a partridge stuffed with a pigeon. All of this was put in a pastry case, called a coffin and was served surrounded by jointed hare, small game birds and wild fowl. Small pies known as chewets had pinched tops, giving them the look of small cabbages or chouettes.

And to wash it all down, a drink from the Wassail bowl. The word ‘Wassail’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon ‘Waes-hael’, meaning ‘be whole’ or ‘be of good health’. The bowl, a large wooden container holding as much as a gallon of punch made of hot-ale, sugar, spices and apples. This punch to be shared with friends and neighbours. A crust of bread was placed at the bottom of the Wassail bowl and offered to the most important person in the room – hence today’s toast as part of any drinking ceremony.