“The House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England.”

This was the statement made in an historic move whereby the House of Lords was abolished on the 19th March 1649 by an Act of Parliament.

Deemed to be a threat, the House of Lords would not meet until twelve years later in 1660 after the restoration of the monarchy.

Such an act was a demonstrably revolutionary decision to change the status quo in politics and overthrow the current system.

Whilst the abolition did not have consent from the monarchy or the Lords, it was a hugely symbolic manoeuvre which challenged the established order.

The significance of the House of Lords as a governing body could not be underestimated, having its roots in medieval England.

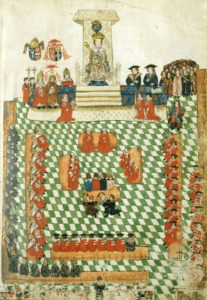

The House of Lords arose from the Magnum Concilium (Great Council) which provided advice to the kings of the Middle Ages. Consisting primarily of ecclesiastic figures and noblemen, the barons were used to give counsel to the king on a variety of significant decisions. Despite this, the monarchs were often partial to ignoring the opinions with which they differed, necessitating the Magna Carta in 1215, designed to resolve such differences.

By 1257, Edward I was calling Parliament meetings by inviting representatives from each shire in the country. At this point, the representatives were split into different groups depending on their status.

In 1295 the “Model Parliament” was held, consisting of ecclesiastical figures, barons and representatives from the various shires, the first of many English Parliament’s to be convened.

Over time the power of the Parliament would rise and fall in tandem with the ebbs and flows of monarchical rule.

Under the rule of Edward III, Parliament would be transformed into a bicameral institution, with barons summoned to the Upper House. In this period, the Lower House was experiencing great change as the political ramifications of the House were strengthened by its legitimacy to grant taxes.

Whilst authority was still housed with the barons of the Upper House, the Lower House was strengthening in its capacity to make political decisions and thus represented a crucial moment in English history which would be built upon in subsequent generations.

By the time Henry VIII was in power, the Parliament was transforming further, acquiring new influence and renewed status as the king required its input in the rather difficult process of navigating the English Reformation.

By the fifteenth century, Parliament resembled something more familiar to us, consisting of an Upper House which was the House of Lords and the Lower House delineating the House of Commons, both more powerful than they had ever been before. Although the Upper House still retained greater power as the nobility and landowners of the country, a new system was imbedding itself into society, culture and politics.

The Upper House consisted of two Archbishops and 24 Diocesan Bishops alongside hereditary peers, those who were awarded peerages and the Law Lords from the High Courts. This was a powerful institution, however in the coming centuries the Lower House would begin to expand and grow in influence, reaching its peak in the seventeenth century and thus leading to conflict.

This turbulence and hostility had been escalating since 1642 under the banner of the English Civil War, which could be more accurately described as a series of consecutive civil wars between two groups, the Parliamentarians more colloquially known as the Roundheads against the Royalists who were familiarly called the Cavaliers.

The conflict lasted for roughly ten years and tossed around the future of English governance between people with varying ideas and values.

The basic divergence of opinion between the two was over the Roundheads’ belief that parliament should have ultimate executive control whilst the Cavaliers believed in the divine right of kings and thus the principle of absolute monarchy.

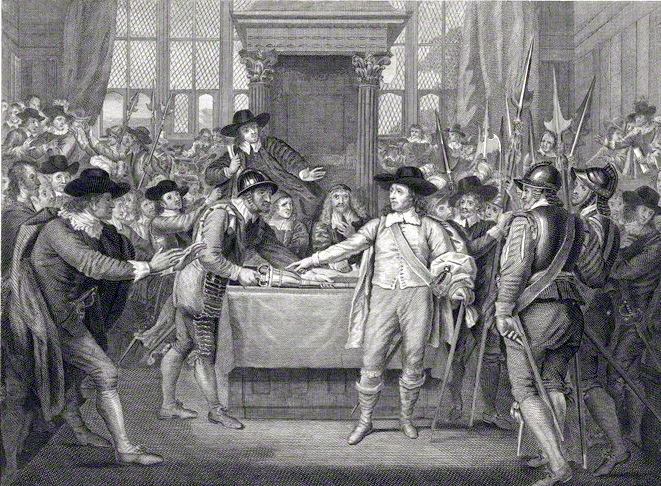

By 1649, the participants were in the throes of the third outbreak of violence. Where Roundheads such as Thomas Fairfax, Edward Montagu and Robert Devereaux had been striving for a constitutional monarchy where parliament held most sway, the more radical elements of their support began to grow louder in their convictions. So much so, that Oliver Cromwell emerged to take action, demanding not a constitutional monarchy but the complete abolition of one altogether.

In the midst of the English Civil War, the power of the establishment was vehemently undermined and challenged.

Thus, the stage was set: King Charles I had his fate sealed and he was subsequently tried and on 30th January 1649 he was executed. In his place stood the Commonwealth of England, now under the watchful eye of Oliver Cromwell.

This was a significant moment in English history: never before had a king been executed.

Oliver Cromwell, now the Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland oversaw the changes he so greatly desired. The king now beheaded, on the 17th March the monarchy was abolished.

Two days later, yet another momentous step was taken to ensure that any royal sympathisers did not exercise their power.

The House of Lords was identified by Cromwell and the fellow Roundheads as a stumbling block to their plans. Although some of their power had seeped away in 1642 with the Bishops Exclusion Act, the upper chamber still consisted of powerful royalists who could potentially scupper the Parliamentarians path to victory.

Therefore, only two days after the abolition of monarchy, the House of Lords was dissolved by an Act of Parliament.

Now a republic, the new parliament became known as the “Rump Parliament” with new and extended powers, no longer answerable to a monarch.

Despite this, Cromwell and his men still had a task on their hands, which included quelling any signs of dissent. As leader, Cromwell took a prominent role in subduing the mutinies of the “Leveller Movement” which fought for suffrage and sovereignty.

Finally, on 3rd September 1651 the war ended in a victory for the Roundheads and the Rump Parliament.

Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell had now replaced the Upper House with a new governing body amounting to around fifty members, all hand-picked.

Sadly for Cromwell the following years would be no plain sailing, as infighting amongst parliamentarians hindered the progress he so desired.

In 1653 the Rump Parliament was replaced with the Barebones Parliament however this did not help matters as it remained increasingly difficult to monitor and control.

At one point, in his role as Lord Protector, Cromwell went as far as to close down the Lower House, claiming “You are no Parliament”, whilst the Speaker was physically accosted and removed from his seat.

This period became known in British history as the Protectorate, lasting from 1653 until its collapse under Cromwell’s son, Richard, in 1659.

The Cromwellian government designed to hold power eventually crumbled as Richard Cromwell, who inherited the mantel from his father, was unable to control the army and in May 1659 gave up and resigned.

The English Interregnum which began with the execution of Charles I was finally over.

In 1660 Charles II reclaimed his throne, the one to which he had been entitled since the death of his father in 1649.

In his Declaration of Breda, Charles II appealed to Parliament offering concessions in order to resume his rightful position.

Thus a final resolution was agreed by both parties, by which they decided to put this experimental decade of republicanism behind them in favour of a restored monarchy.

As Charles II returned to the throne, so too did the House of Lords reassemble in their previous home in the upper chamber.

Traditional power, position and prestige had been restored, marking the end of a hostile, turbulent and revolutionary moment in British history.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 18th February 2022.