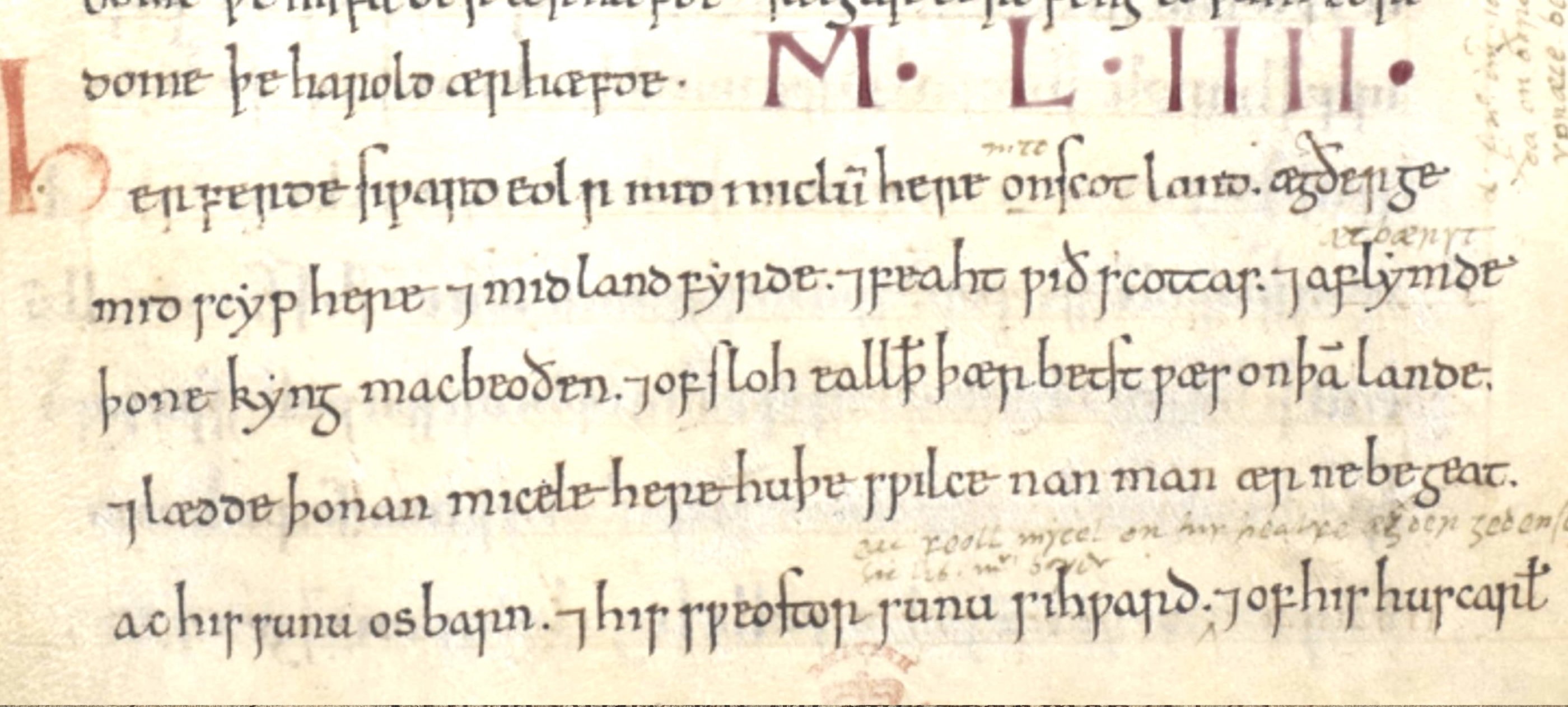

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a compilation of annals telling the history of the Wessex dynasty revealing the trials and tribulations of kingship, the development of Christianity, Anglo-Saxon culture and so much more.

As a primary historical source it provides knowledge of the period, containing information, anecdotes and quotes which would otherwise have been lost forever.

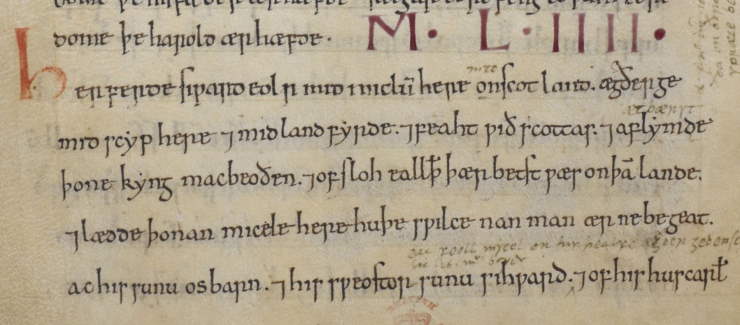

Today it remains one of the few sources pertaining to this eventful period of English history, capturing the unfolding events in the Old English vernacular. It is the oldest history of a European country in its vernacular, thus demonstrating its immeasurable value for knowledge of the Anglo-Saxon period.

Together with Bede’s “Ecclesiastical History of the English People”, the Chronicle provides an insight into the history of the English in the period following the Romans right up until the point of the Norman Conquest.

Originally compiled in the ninth century during the reign of King Alfred the Great, its original manuscript intended to be a national chronicle of events giving a detailed yearly account of English history.

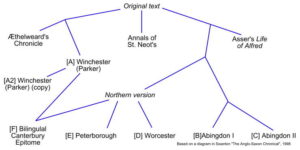

It was the first of its kind and drew on other sources to enhance its narrative such as smaller annals and Venerable Bede’s work in order to compile a detailed manuscript. By the year 890 multiple copies of the original chronicle were already in circulation, often housed in monasteries around the country.

Thus in their new ecclesiastical homes, these manuscripts were often enhanced and supplemented by each individual monastery leading to variations, whilst the Chronicle itself continued to grow for another hundred years.

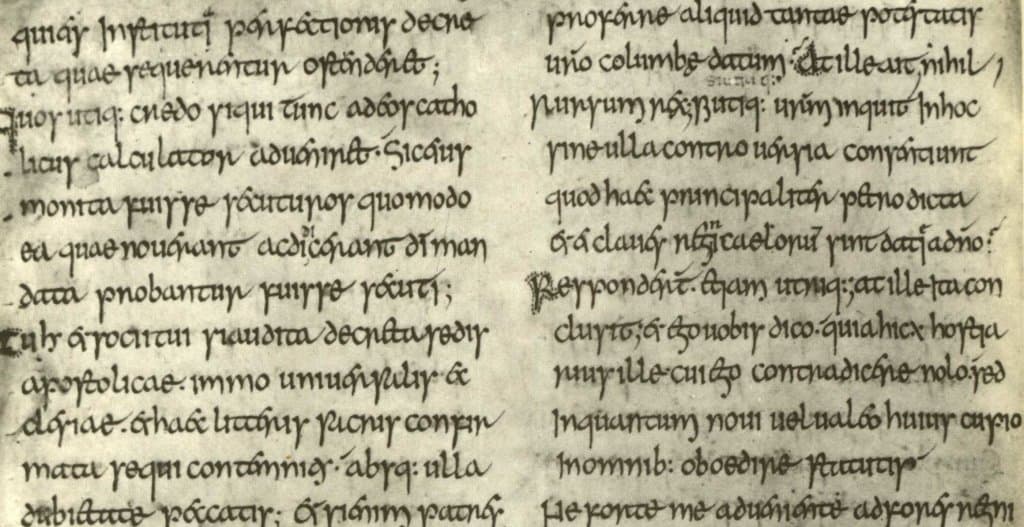

In total, there were nine manuscripts written in the vernacular, whilst the last one also provides a translation into Latin. Today, seven surviving manuscripts along with fragments are housed predominantly in the British Library as well as at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

One of the narratives believed to be the oldest is the Winchester Chronicle and often known as the Parker Chronicle (alphabetically referred to as Chronicle A) dating back to the year 891 during the reign of Alfred the Great.

The narrative’s first section begins with accounts pertaining to the church as well as an overview of the history of the Roman Empire. One could argue that much of this material would have been inspired by Bede’s work on similar themes.

In addition to these early entries in the Chronicle, the first manuscript draws heavily on oral traditions and the telling of legends in order to explain the foundations of the Angles and Saxons arriving in England and the development of various competing kingdoms alongside the advent of Christianity.

Later on in the Chronicle, the focus remains on telling the story of the rise of the House of Wessex and its glory years which are vividly depicted in Anglo-Saxon prose, highlighting the tale of the West Saxons in their struggle to defeat the Danes and the kingship of Alfred the Great.

Also contained with the manuscript are four poems, one of the most famous being about the Battle of Brunanburh, thought to be one of the finest examples of Anglo-Saxon battle poetry which was later modernised by the famous poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson in 1880.

Aside from important battles being recorded, other events described in the narrative included the arrival of King Cnut and the advent of William the Conqueror in 1066.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle provides historians a variety of depictions of Anglo-Saxon life, not only reflecting the battles, politics and power of kingship but the mentality of Anglo-Saxons as a community of fighters, not only as warriors on the battlefield but as those who fought to cement their way of life and settle as a group of people within their own ideals and cultural norms.

The second manuscript known as Chronicle B, provides the next instalment of entries with a dual commentary on Edward the Elder as well as the activities of his sister, Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians.

Alongside the following Chronicle C, believed to be composed at Abingdon Abbey, the manuscripts use of the Mercian Register (a group of annals) provides information about Aethelflaed whilst also separately focusing on her brother, Edward the Elder and his exploits during the same period.

The Chronicle delivers an important insight into a powerful woman in the kingdom of Mercia until her death in 918. Aethelflaed was the eldest child of King Alfred of Wessex and would subsequently gain more power when she married Aethelred, Lord of Mercia. With the royal power now spreading between kingdoms, her husband’s death in 911 only served to enhance her status as she became ruler of Mercia with territory expanding in all directions.

The Chronicle’s depiction of the Lady of Mercia is therefore a crucial point in Anglo-Saxon history, depicting a woman with power in her own right who led armies and expanded her powerbase.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle C alongside its depiction of Aethelflaed also contains poems and describes the eventful reigns of King Aethelred the Unready, followed by his son, Edmund Ironside and the takeover of King Cnut.

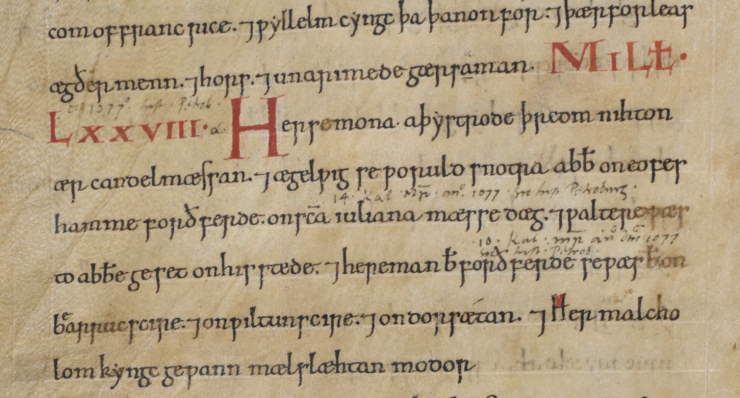

The subsequent Chronicle D however shifts focus and is believed to have been compiled in the north with its emphasis on events in Worcester and York. The entries discuss events in the period from 1050s up until 1070s, including details such as the coronation of King William I at Westminster Abbey.

In addition, this particular manuscript includes the only recorded arrival of William the Conqueror and his meeting with Edward the Confessor before returning to Normandy, preceding the events of his conquest.

The consecutive chronicle, manuscript E, also referred to as the Peterborough Chronicle is currently housed at the Bodleian Library and was written after a fire at the monastery in 1116. One of the most interesting details within this narrative is its account of the period in English history known as “The Anarchy” under the reign of King Stephen who had usurped Empress Matilda to the throne.

The following manuscript known by the letter F, was composed at Christ Church, Canterbury in the late eleventh century. Most notably, this later manuscript is the first of its kind to provide translation in Latin after each section of Old English.

Numerous other fragments also survive in various forms and includes the Easter Table annals that were also constructed in Canterbury in the eleventh century.

Whilst each manuscript was written and edited by different figures within each monastery that housed it, the bias which it naturally contains does not obliterate the powerful nature of such a source for this period of English history.

The Chronicle’s mixed authorship only enhances its narrative voice, written in the vernacular by real Anglo-Saxons who told stories about battles, kings, society, religion and topics which interested them, in itself tells a story in its own right.

Whilst some figures and themes are covered better than others, many of these details, events and recollections would simply not have been recorded anywhere else.

In literary terms, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also is greatly significant for its demonstration of Anglo-Saxon prose, poetry form and construction as well as the demonstration of Old English and its transition into Middle English during the time of the Peterborough Chronicle.

Today many of us take for granted the ability to access knowledge about topics, themes and events we are interested in however, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reminds us of the importance of individuals throughout history who gave their time to record and pass on knowledge, so that this rare glimpse of a life that has long since been lost, could be enjoyed and studied for centuries to come.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 25th November 2022.