In the Christian church, an archbishop is a bishop of superior rank who has authority over other bishops in an ecclesiastic province or area. The Church of England is presided over by two archbishops: the archbishop of Canterbury, who is ‘primate of All England’, and the archbishop of York, who is ‘primate of England’.

In the time of St. Augustine, around the 5th century it was intended that England would be divided into two provinces with two archbishops, one at London and one at York. Canterbury gained supremacy just prior to the Reformation in the 16th century, when it exercised the powers of papal legate throughout England.

It is the Archbishop of Canterbury who has the privilege of crowning the kings and queens of England and ranks immediately after the princes of royal blood.

The Archbishop’s official residence is at Lambeth Palace, London, and second residence at the Old Palace, Canterbury.

The first Archbishop of Canterbury was Augustine. Originally prior to the Benedictine monastery of St. Andrew in Rome, he was sent to England by Pope Gregory I with the mission to convert the natives to Roman Christianity.

Landing in Ebbesfleet, Kent in 597 Augustine quickly converted his first native when he baptized Ethelbert, King of Kent along with many of his subjects. He was consecrated Bishop of the English at Arles that same year and appointed archbishop in 601, establishing his seat at Canterbury. In 603 he attempted unsuccessfully to unite the Roman and native Celtic churches at a conference on the Severn.

The following list traces the Archbishops from the time of Augustine through the Reformation, up to the present day. Their influence on the history of England and the English people is apparent for all to see.

Archbishops of Canterbury

| 597 | Augustine | ||

| 604 | Laurentius. Nominated by St. Augustine as his successor. Had a rocky ride when King Ethelbert of Kent was succeeded by his pagan son Eadbald. Remaining calm Laurentius eventually converted Eadbald to Christianity, thus preserving the Roman mission in England. | ||

| 619 | Mellitus | ||

| 624 | Justus | ||

| 627 | Honorius. The last of the group of Roman missionaries who had accompanied St. Augustine to England. | ||

| 655 | Deusdedit | ||

| 668 | Theodore (of Tarsus). The Greek theologian was already in his sixties when he was sent to England by Pope Vitalian to assume the role of archbishop. Despite his age he went on to reorganise the English Church creating the diocesan structure, uniting for the first time the people of England. | ||

| 693 | Berhtwald. The first archbishop of English birth. Worked with King Wihtred of Kent to develop the laws of the land. | ||

| 731 | Tatwine | ||

| 735 | Nothelm |

|

|

| 740 | Cuthbert. Established England as an important base from which Anglo-Saxon missionaries were dispatched abroad. | ||

| 761 | Bregowine | ||

| 765 | Jaenberht. Backed the wrong horse in the King of Kent against King Offa of Mercia. He saw the importance of Canterbury reduce as power shifted to Offa’s cathedral in Lichfield. | ||

| 793 | Ethelheard, St. Originally chosen by King Offa of Mercia, to make Lichfield into the premier archbishopric in England. Ethelheard appears to have messed things up a little in the politics of the day, and unwittingly succeeded in reinstating Canterbury’s traditional superiority. | ||

| 805 | Wulfred. As with his predecessors Wulfred’s rule was frequently disrupted by disputes with the kings of Mercia and was at one stage exiled by King Cenwulf. | ||

| 832 | Feologeld | ||

| 833 | Ceolnoth. Maintained Canterbury’s superiority within the Church of England by forming close relationships with the rising power of the Kings of Wessex, and abandoning the pro-Mercian policies of Feologeld. | ||

| 870 | Ethelred | ||

| 890 | Plegmund. Appointed Archbishop by Alfred the Great. Plegmund played an influential role in the reigns of both Alfred and Edward the Elder. He was involved in early efforts to convert the Danelaw to Christianity. | ||

| 914 | Athelm | ||

| 923 | Wulfhelm | ||

| 942 | Oda. Oda’s career serves to demonstrate the integration of Scandinavians into English society. The son of a pagan who came to England with the Viking ‘Great Army’, Oda organised the reintroduction of a bishopric into the Scandinavian settlements of East Anglia. | ||

| 959 | Brithelm | ||

| 959 | Aelfsige | ||

| 960 | Dunstan. He was originally Abbot of Glastonbury from 945, and made it a centre of learning. He was King Edred’s chief advisor and virtually became the kingdom’s ruler. Following the death of Edred in 955, his nephew King Edwy drove Dunstan into exile for refusing to authorize his proposed marriage with Ælfgifu. After Edwy’s death in 959, Dunstan became Archbishop of Canterbury from 960. He is said to have pulled the devil’s nose with a pair of tongs. His feast day is 19th May. | ||

| 988 | Ethelgar | ||

| 990 | Sigeric. In the reign of Ethelred II the Unready, Sigeric was promoted from humble monk to the top job of archbishop. He is associated with the policy of paying Danegeld in an attempt to buy off Scandanavian attacks. | ||

| 995 | Aelfric | ||

| 1005 | Alphege. In 1012, he was captured by the Danes who had invaded Kent, and was held at Greenwich. He refused to pay his own ransom, and, during a drunken feast at which the Danes threw left-over bones and skulls at Alphege, he was murdered by a Dane whom he had converted to Christianity earlier in the day., The Danish leader, Thorkill, was disgusted by the murder and changed sides, bringing 45 ships to Æthelred ‘s service. In 1033, Canute moved Alphege’s bones from St Paul’s Cathedral to Canterbury Cathedral. | ||

| 1013 | Lyfing | ||

| 1020 | Ethelnoth. One of the most distinguished of the Anglo-Saxon archbishops. The first monk of the Canterbury monastery to be elected archbishop. | ||

| 1038 | Eadsige | ||

| 1051 | Robert of Jumieges. One of a small number of Normans who came to England with Edward the Confessor in 1041. His scheming and elevation to archbishop fuelled a civil war between Edward and Earl Godwine of Wessex. Robert was also the ambassador who promised the succession to Duke William (The Conqueror) of Normandy. | ||

| 1052 | Stigand. Became archbishop after the expulsion of Robert of Jumieges, as such he was never recognised by the church in Rome. A worldly and very wealthy man he was at first accepted by William I The Conqueror, but in 1070 was deposed by Papal Legate. | ||

| 1070 | Lanfranc. A native of Italy, he left home around 1030 to pursue his studies in France. He was responsible for presenting the case to the Pope for William of Normandy’s claim to the English crown. It was William I The Conqueror who appointed him archbishop in 1070. Lanfranc was responsible for reforming and reorganising the English Church and rebuilt the Cathedral on the model of St Stephen’s in Caen where he had previously been Abbot. | ||

| 1093 | Anselm. Another Italian who had left home in search of better things and had found Lefranc as Prior at the Norman Abbey of Bec. He followed in Lefranc’s footsteps first as Prior and then as Archbishop. His strongly held views on the Church-State relationship would greatly influence Thomas a Becket and continue to rumble on for centuries ensuring a greater control of the Church from Rome. | ||

| 1114 | Ralph d’Escures | ||

| 1123 | William de Corbeil | ||

| 1139 | Theobald. Yet another monk from the Norman Abbey of Bec. He was created Archbishop by Stephen. The relationship between the King and Archbishop strained over the years culminating in Theobald refusing to crown Stephen’s son Eustace. He drew Thomas a Becket into his service | ||

| 1162 | Thomas a Becket. Worked as a banker’s clerk before entering the service of Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury in 1145. He was a close friend of Henry II and was Chancellor from 1152 until 1162, when he was elected archbishop. He then changed his allegiance to the church, alienating Henry. In 1164, he opposed Henry’s attempt to control the relations between church and state – preferring the clergy to be judged by the church and not by the state – and fled to France. There was a reconciliation between Henry and Becket and he returned in 1170, but the reconciliation soon broke down. After an outburst from the king, four knights – probably misunderstanding Henry’s instructions – murdered Becket in front of the altar of Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December 1170. He was canonised – as St Thomas Becket – in 1172, and his shrine became the most popular destination of pilgrimage in England until the Reformation. His feast day is 29th December. |

||

| 1174 | Richard (of Dover) | ||

| 1184 | Baldwin. Despite being described as gentle and guileless, he did take action when needed, galloping up and saving Gilbert of Plumpton from the gallows, forbidding such hangman’s work on a Sunday. Also saw action in the Crusades, he died five weeks after his 200 knights had fought at Acre. | ||

| 1193 | Hubert Walter. Rector of Halifax in 1185. He travelled to the Holy Land with Richard the Lion-Heart on the Third Crusade 1190 and, when Richard was taken prisoner by emperor Henry VI, Walter brought the army back to England and raised a ransom of 100,000 marks for the king’s release. He was Dean of York from 1186 to 1189, then Bishop of Salisbury, and he became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1193. On Richard’s death in 1199, he was appointed Chancellor | ||

| 1207 | Stephen Langton. He was consecrated archbishop by Pope Innocent III, which annoyed King John so much that he refused to admit him into England. The quarrel between King and Pope lasted until John submitted in 1213. Once in England he proved to be an important mediator playing a key role in negotiating Magna Carta. | ||

| 1229 | Richard le Grant | ||

| 1234 | Edmund of Abingdon. He taught theology at Oxford before becoming archbishop. Following quarrels with Henry III and the monks of Canterbury he went to see Rome, and died! | ||

| 1245 | Boniface of Savoy | ||

| 1273 | Robert Kilwardby. Educated in Paris, he taught theology at Oxford before becoming archbishop. Created Cardinal Bishop of Porto in 1278. | ||

| 1279 | John Peckham. A highly respected theologian who taught at Paris and Rome. He tried in vain to reconcile the differences between Edward I and Llwelyn Ap Gruffudd. | ||

| 1294 | Robert Winchelsey. Made an enemy of Edward I (Longshanks) when he refused to pay taxes without the Pope’s permission. | ||

| 1313 | Walter Reynolds | ||

| 1328 | Simon Meopham | ||

| 1333 | John de Stratford. He was a chief advisor to Edward III and played a key role in the onset of the Hundred Year War. The King accused him of incompetence after the failure of his 1340 campaign. | ||

| 1349 | Thomas Bradwardine. One of the most learned men ever to be archbishop. He accompanied Edward III to Flanders in 1338 and helped to negotiate terms with Philip of France after the Battle of Crécy in 1346. He was elected archbishop while in France in 1338, but promptly died of the Black Death only days after his return to England | ||

| 1349 | Simon Islip | ||

| 1366 | Simon Langham. Forced to resign from the post in 1368 by Edward III. He was again elected archbishop in 1374, but the Pope would not let him go and he died at Avignon. | ||

| 1368 | William Whittlesey | ||

| 1375 | Simon Sudbury. He was blamed for government mismanagement and unjust taxation which led to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, led by Wat Tyler. The ‘revolting’ rebels dragged him from the Tower of London and beheaded him. His mummified head is displayed in the vestry of St. Gregory’s church in Sudbury, Suffolk. | ||

| 1381 | William Courtenay. He led the opposition within the English Church to John Wyclif, dubbed by some to be ‘the morning star of the Reformation’, and the Lollards, and was influential in driving them out of Oxford. | ||

| 1396 | Thomas Arundel. The combination of his high aristocratic birth and driving ambition made him one of the most powerful men in England. His political connections led first to his banishment by Richard II in 1397, and then to his restoration by Henry IV two years later. | ||

| 1398 | Roger Walden. | ||

| 1399 | Thomas Arundel (restored). | ||

| 1414 | Henry Chichele. He helped to finance the war against France, organised the fight against Lollardy and founded All Souls College in Oxford. | ||

| 1443 | John Stafford. It was said of him if he had done little good he had done no harm. | ||

| 1452 | John Kempe. Initially Henry V’s Keeper of the Privy Seal and Chancellor in Normandy, he also served two terms as Chancellor of England. Before becoming Archbishop of Canterbury he was Bishop of; Rochester (1419-21), Chichester (1421), London (1421-5) and York (1425-52). | ||

| 1454 | Thomas Bourchier. Also served as Chancellor of England from 1455 to 1456, during an illness of Henry VI and while Richard of York was Protector. | ||

| 1486 | John Morton. Originally an Oxford-trained lawyer he fled to Flanders, to the court of Henry Tudor, after Richard III attempted to imprison him in 1483. Henry VII summoned him home after his victory at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 and made him archbishop. After this he applied much of his energy to financial matters of state giving his name to the ‘Morton’s fork’ principle of tax assessment: ostentation is proof of wealth – stricken appearance is proof of hidden savings. | ||

| 1501 | Henry Deane. | ||

| 1503 | William Warham. He expressed doubts as to the wisdom of Henry VIII marrying Catherine of Aragon, the widow of Prince Arthur, but presided at their coronation. He did nothing to help Catherine against Henry’s efforts to have their marriage declared null, but was less than happy with the increasingly anti-papal royal policy adopted after 1530. | ||

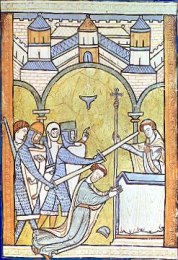

The martyrdom of Thomas Cranmer, from an old edition of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs |

|||

Archbishops of Canterbury since the Reformation |

|||

| 1533 | Thomas Cranmer. Compiled the first English Book of Common Prayer. First Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1551, his 42 Articles laid down the basis of Anglican Protestantism. Burned at the stake for heresy and treason in opposing Bloody Mary. His feast day is 16th October. | ||

| 1556 | Reginald Pole. Returned from a self imposed exile in Italy following the accession of his Catholic cousin Queen Mary I. He died within a few hours of her in November 1558. | ||

| 1559 | Mathew Parker. He was apparently surprised when Elizabeth I decided that her mother’s (Anne Boleyn) old chaplain would make an ideal Archbishop of Canterbury. Presided over the very difficult opening years of the new religious settlement. | ||

| 1576 | Edmund Grindal. He had been exiled under Queen Mary I because of his Protestant beliefs and was therefore the obvious choice for the top job in the Church of Elizabeth I. His defiance of her wishes in 1577 however, led to his suspension under house arrest. He failed to recovered favour by the time of his death. | ||

| 1583 | John Whitgift. A former Cambridge don, he first attracted the attention of Elizabeth I by his strict disciplining of the non-conforming Puritans. Yet another archbishop who annoyed the lady, with the thought that a clergyman should attempt to decide theology for her Church. | ||

| 1604 | Richard Bancroft. Was born and initially educated in Farnworth, near modern day Widnes, he graduated from Cambridge and was ordained around 1570. Whilst still Bishop of London, he drafted the rules for the translation of what would eventually become the ‘most popular book in the world’ …The King James Bible. | ||

| 1611 | George Abbot. He found favour under James I, his reputation as a churchman however was dented when he accidentally killed a gamekeeper whilst out hunting with a crossbow. | ||

| 1633 | William Laud. His High Church policy, support for Charles I, censorship of the press, and persecution of the Puritans aroused bitter opposition. He was responsible for moving the altar from a its central position to the east end of churches. His attempt to impose the Prayer Book in Scotland precipitated the Civil War. He was impeached by the Long Parliament in 1640, imprisoned in the Tower of London, condemned to death, and beheaded. | ||

| 1660 | William Juxon. A friend of William Laud, he had attended Charles I at his execution in 1649 and spent the years until the restoration of Charles II in retirement. His appointment as archbishop in 1660 being a reward for loyal royal service. | ||

| 1663 | Gilbert Sheldon. Another former advisor to Charles I, he attempted to unite the thinking of the Anglican and Presbyterian branches of the Church. | ||

| 1678 | William Sancroft. Following an unsuccessful attempt to convert King James II to Anglicanism, he and the king fell out. He openly and publicly defied royal orders to accept the King’s Declaration of Indulgence for Dissenters and Catholics. A man of integrity it appears, as he played no part in Glorious Revolution and argued that the oath he had taken to James precluded him taking another to William III and Mary II. | ||

| 1691 | John Tillotson. He succeeded Sancroft as archbishop, having carried out the duties of the office since 1689 when Sancroft had refused to take the oaths that recognised William and Mary as rightful monarchs. |

William of Orange |

|

| 1695 | Thomas Tenison. A ‘friend’ of those who invited William of Orange to England in 1688. He warned about the threat to Anglicanism from a Stuart restoration. | ||

| 1716 | William Wake. He attempted to persuade the French Gallican Church to break with Rome and ally itself with the Church of England. In later life he gained a reputation for corruption, appointing members of his family to financially lucrative positions within the Church. | ||

| 1737 | John Potter | ||

| 1747 | Thomas Herring. As Archbishop of York he was influential in raising funds to support George II against to Jacobite rebellion. So effective was he that he was rewarded with the ‘top job’ in 1747. | ||

| 1757 | Matthew Hutton. | ||

| 1758 | Thomas Secker. | ||

| 1768 | Hon. Frederick Cornwallis. | ||

| 1783 | John Moore. | ||

| 1805 | Charles Manners Sutton. | ||

| 1828 | William Howley. | ||

| 1848 | John Bird Sumner. | ||

| 1862 | Charles Thomas Longley. A former Headmaster of Harrow School. He served as inaugural Bishop of Ripon, as Bishop of Durham, as Archbishop of York, and then as Archbishop of Canterbury for six years from 20 October 1862 until his death. | ||

| 1868 | Archibald Campbell Tait. The first Scotsman to hold the most senior post in the Church of England, he did much to organise the Church throughout the colonies. His biography was published by his son-in-law, the future archbishop Randall Thomas Davidson. | ||

| 1883 | Edward White Benson. A former Birmingham schoolboy, as Archbishop of Canterbury he became a trusted confidant of Queen Victoria. On 11 October 1896 while returning from a tour of Ireland, he died suddenly of a heart attack during confession in morning prayer at Hawarden Parish Church, North Wales. | ||

| 1896 | Frederick Temple. Followed the well worn path from Oxford to Rugby to Canterbury. | ||

| 1903 | Randall Thomas Davidson. Born in Edinburgh into a Presbyterian family, he studied at Oxford, and became chaplain to Archbishop Tait (his father-in-law) and also to Queen Victoria. | ||

| 1928 | Cosmo Gordon Lang. Born in Fyvie, Aberdeenshire, he was Principal of Aberdeen University and entered the Church of England in 1890. He was both counsellor and friend to the royal family. | ||

| 1942 | William Temple. The son of Frederick Temple he deviated the well worn path from Oxford to Canterbury via Repton. He was an outspoken supporter of social reform in crusades against money lenders, slums and dishonesty. | ||

| 1945 | Geoffrey Francis Fisher. He also followed the now deeply rutted path from Oxford to Repton to Canterbury. As archbishop he crowned Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey in 1953. | ||

| 1961 | Arthur Michael Ramsey. Educated at Repton, where his headmaster was the man he would succeed as archbishop – Geoffrey Fisher, he worked for Church unity with an historic visit to the Vatican in 1966. He also attempted to forge a reconciliation with the Methodist Church. | ||

| 1974 | Frederick Donald Coggan. The first archbishop of Canterbury to support the ordination of women; the church eventually admitted women to the priesthood in 1994. He fostered better relations between Christians and Jews and publicly denounced racial intolerance as well as nuclear arms. In 1980 he was elevated to a life peerage as Baron Coggan of Canterbury and of Sissinghurst. | ||

| 1980 | Robert Runcie. Oxford educated, he served with the Scots Guards during WWII, for which he was awarded an MC. He was ordained in 1951 and was Bishop of St.Albans for 10 years before being consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury. His office was marked by a papal visit to Canterbury and the war with Argentina, after which he urged reconciliation. | ||

| 1991 | George Carey. Born in London, he left school at 15 without any qualifications. After National Service in Egypt and Iraq, he felt called to the priesthood. A supporter of the ordination of women, he represented the liberal and modern aspects of the Church of England. | ||

| 2002 | Rowan Williams. The first Welshman to be selected to the Church of England’s top job for at least 1000 years, he was elected the 104th archbishop on 23rd July 2002. | ||

| 2013 | Justin Welby. At his installation ceremony Welby became the first archbishop of Canterbury to be enthroned by a woman cleric. As the archbishop of Canterbury, Welby officiated at the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II on September 19, 2022. In November 2024, Welby announced his resignation as the archbishop of Canterbury following a review of the Church of England’s handling of child abuse cases. | ||

| 2026 | Sarah Mullally. The first woman to hold the most senior position in the Church of England, she succeeds Justin Welby, who resigned in 2024. | ||