Women have always accompanied armies, both in peacetime and on campaign. Their place was usually following along behind the soldiers, accompanying the waggons and pack animals bearing all the necessities of everyday life. This is reflected in the names often allocated to this mostly civilian rearguard: the baggage train, and camp followers.

However, neither of these terms really does justice either to the range or the individuality of the women who were involved with the English, and subsequently British army, from the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (the “Civil War”) to the eve of the Napoleonic Wars and Britain’s global imperial expansion. They were much, much more than sex workers and sock washers, although popular fictional accounts often delight in portraying them in this way.

For one thing, it was certainly not uncommon for women to engage as combatants themselves, and this is well-documented from the seventeenth century onward. One of the best-known is Jane Ingleby (“Trooper Jane”) of Ripley Castle in Yorkshire, who fought alongside her brother William in Prince Rupert’s Horse. Jane was in her forties when she went to war, and after Marston Moor she held Cromwell at pistol point all night when his forces attacked and entered Ripley Castle. The boots she wore in combat disguised as a man allegedly still exist and are in the possession of the family.

Royalist women combatants had a good example in Charles I’s wife Henrietta Maria, who came to be known as the “She-Majesty Generalissima” for her efforts in raising support for the king. There were so many women serving in the Royalist army that at one point Charles had to issue a stern edict against their participation.

Parliamentarian women were no less brave, though there were far fewer of them serving as soldiers. Anne Dymock was one. Refusing to be parted from her husband, she dressed as a man and took on the identity of his brother so they could serve in the army together. Women on both sides of the conflict also defended their family homes through sieges and bombardment.

In later years, the famous Christian Davies (“Kit Cavanagh”) disguised herself as a man and fought in Marlborough’s armies.

She achieved the remarkable status of becoming the first female Chelsea Pensioner. When the identity of these women was revealed they frequently came in for praise from their commanding officers as simply good soldiers who had served well. They also entered folklore in rhymes and songs such as “The Pretty Drummer Boy”, “The Gallant She-souldier”, and “Sweet Polly Oliver”, who “cut her hair close, and stained her face brown, and went for a soldier to fair London town” in order to follow her lover. Most of these ballads take an approving, even admiring view of the phenomenon.

Women who accompanied husbands, lovers or family members not in disguise, but simply to support and care for them on campaign, often turned to wearing men’s clothing as a more practical option. If their menfolk died in battle, they would wear their uniform and carry on in the ranks themselves. This was not simply for patriotic or sentimental purposes. Often they had no other way to support themselves, and nowhere else to go. Financial support for soldiers’ dependents was not a given, and unusual enough to be noted in various army records for rare cases in the seventeenth century.

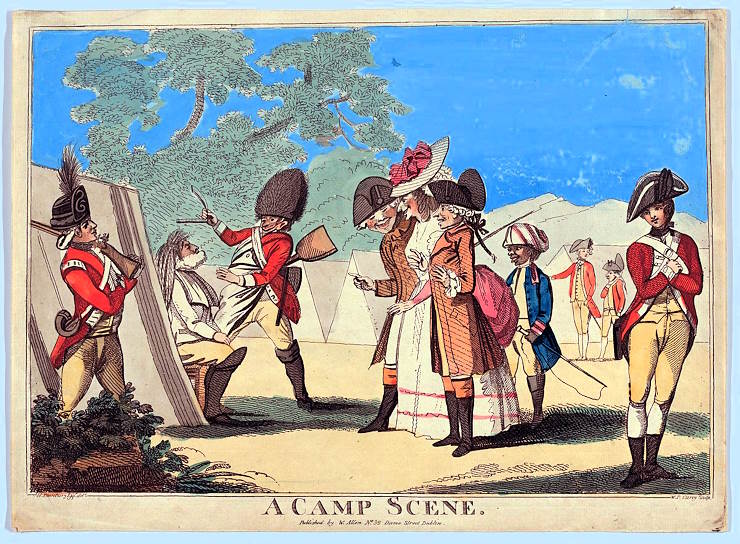

If not actively soldiering, women worked as grooms or in other supporting roles, as well as the more traditional domestic work of mending and cooking. Plus, of course, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they were an unofficial medical corps. Some women went into business as sutlers, providing food and drink to the soldiers and their dependents.

After the establishment of a formal standing army, marriage was not encouraged for men in the military. As early as 1685, a soldier would be in severe trouble for marrying without the approval of his commanding officer, and this remained the case during the following two centuries. However, the authorities realised that armies could not exist without the inclusion and support of women, and grudgingly eventually allowed a percentage of wives – six to every hundred men – to travel with the regiments overseas. The chosen ones were selected by drawing lots, or throwing dice. When drawing lots, the tickets were divided into “to-go” and “not-to-go” and emotional scenes among the “not-to-gos” on being parted from their husbands affected the onlookers very much.

There’s no doubt the army looked on these women as part of a workforce. They were expected to perform certain tasks such as cleaning, laundering and mending, and the army laid down strict rules about their morals. Despite the lottery system, it was believed that wives with no children were more likely to be chosen for overseas service. In 1744 Sir John Pringle described wives and children as an “impediment”, since a soldier’s pay could not support them and this meant shorter rations for the soldier. Soldiers with families seem to have been viewed at times as a nuisance and the families were sometimes paid to return to their homes, which resulted in some traumatic parting scenes and tragic consequences.

Until a special act was passed in 1800 allowing married soldiers to stay in quarters with their wives, there was next to no provision made for housing women with the army, and indeed not much provision for the men. The usual way was to live in tents, or billet soldiers on local people, and in inns and the like. There were regulations that limited women to one per tent of men. Even after the introduction of specially built barrack blocks in the latter half of the eighteenth century, women still found few concessions to their existence.

Married women and their children would live with their husbands in the barrack, their beds often separated from those of the neighbouring soldiers by only a curtain. With an increasingly more professional approach to the military, conditions improved. However, married soldiers and their families would not know the “luxury” of married quarters until the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, there is even a sense that the women who followed the army could be “ranked” like the men. One writer suggested that the first rank consisted of ladies who were wives of senior officers and travelled in coaches. The second rank, or class, was somewhat vaguer, consisting of women who rode on horseback alongside the baggage waggons of “their” regiments. These are described as being rather gadabout, with an official in charge of them with the suggestive title of Hureweibles, or “Marshals of the whores”. The third class, which conjures up a vision of women trudging alongside the waggons, were those who could only afford to travel on foot and were the wives of inferior officers and soldiers. These too were “marshalled” by a regimental officer.

As well as feeding, healing and generally supporting the soldiers, the wives, partners and lovers were also responsible for providing hairdressing services. This was no frivolous matter, particularly in the Hanoverian armies when standards of uniform and appearance were enforced. Soldiers wore their dressed and powdered hair in plaited “queues”, which were fastened up in different ways according to the soldier’s role and position in the ranks. When this task was ordered to be taken away from the women and given to professional male barbers and hairdressers, it led to a near mutiny, as military historian Richard Holmes recounts.

Whatever their role or status, all women in the baggage train were subject to army discipline just like the soldiers. This took many forms, from mild admonishment to sentence of death for mutiny, treachery, or desertion. For serious offenders, the whirligig was a feared punishment. It involved placing the offender in a cage on a revolving platform, which was then spun around and around until the prisoner was dizzy to the point of vomiting and evacuating their bowels. To add insult to injury, this was carried out in front of onlookers from the army who usually found the whole spectacle highly entertaining.

Equally fearsome and to be avoided was the lash, again carried out in front of a crowd, and sometimes in public in the nearest town. This was how one woman, Phoebe Hessel, who had been disguised and serving as a soldier was discovered. When stripped to be whipped for an offence she shouted defiantly “Strike and be damned!” For crimes such as theft, women as well as men were lashed publicly on the “bare back in different portions” and also on the buttocks. There were various punishments for love affairs between married women and soldiers, because of their inevitable effect on discipline. In some cases, affairs led to violence and even murder, which would end in capital punishment. The ultimate non-capital punishment was the “drumming-out” of offenders, whether male or female. This was the equivalent of excommunication from the military and an almost certain route to destitution.

In an age when chastisement of women, children and offenders was accepted, nonetheless soldiers received military sentences for cruel treatment of their wives and families. One such punishment, both intended to humiliate and physically hurt, was doled out in 1669 to a soldier for beating his wife. A petticoat was hung round his neck and he was mounted on a wooden horse, which was an instrument of punishment “ridden” hard by offenders until they’d learned their lesson.

While the lives of women with some official recognition were gruelling enough, their privations were nothing compared with the camp followers with no status or recognition at all. These were the sex workers whose presence was viewed as either as a necessary evil or simply a nuisance. Wherever the army moved they would be there, either women from neighbouring town or country, or longer-term followers on foot. This was a desperate life of living in the open, frequently freezing to death in cold winters or dying in childbirth by the wayside. Pregnancy and high child mortality were equally common, as were alcoholism, disease and violence. Records reveal numerous attempts by army authorities to drive them away.

The hardiness of the army women was revealed in the Duke of Cumberland’s campaign in Scotland, a bloody affair culminating in Culloden in 1746, which earned him the lasting soubriquet of “Butcher Cumberland”. In Scotland, the women following the English army waded through freezing streams with their clothes in bundles on their heads to keep them dry. Prior to the campaign, some of the soldiers had constructed unofficial huts where they could live with their wives. The married soldiers were ordered to get into quarters with the rest of the men and dismiss their wives to the tents. Only “authorised” wives though! All other women were told to depart and shift for themselves in no uncertain terms.

However, in the aftermath of the battle of Culloden, some of the officers’ wives took part in horse races on Galloway horses “taken from the rebels”, riding astride like men. While attitudes of the conquerors at Culloden were somewhat dismissive of Scotland’s premier racehorses (and key contributors to the foundation of the Thoroughbred) nonetheless the soldiers bet very substantial sums on the Galloways and their riders.

Life as a woman with army connections did have its more pleasurable aspects, including attendance at balls. Surprisingly, given their stern views on marriage, the military authorities looked on balls and similar events with approval, as they felt they had a civilising effect on soldiers (and therefore presumably on discipline). Anyone familiar with the work of Jane Austen will know that the arrival of an army camp of Redcoats in the neighbourhood was likely to induce palpitations in parents and daughters alike – for different reasons. Often the last thing any parent of means wanted for their daughter was marriage to a soldier, however elevated his rank. All too often though, the lure of the smart uniform, the musket, fife and drum, and the urgency of the likelihood of the regiment moving on, proved irresistible to young women.

If they ultimately “followed the drum” and attempted to make a successful life with their soldier, they had to have as much grit as their man. Women serving in and following the armies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries suffered the same privations as the men (and more), were subject to the same discipline, had even less security, and were responsible for more dependents. They witnessed and experienced everything the men did and were active during and in the aftermath of engagements, often carrying wounded soldiers and corpses from the battlefield. Some fought alongside the men, both in disguise and openly.

In short, they were not just the women of the baggage train or camp followers and a logistical and disciplinary headache for the military top brass. They soldiered through life themselves and were an essential part of the success of campaigns.

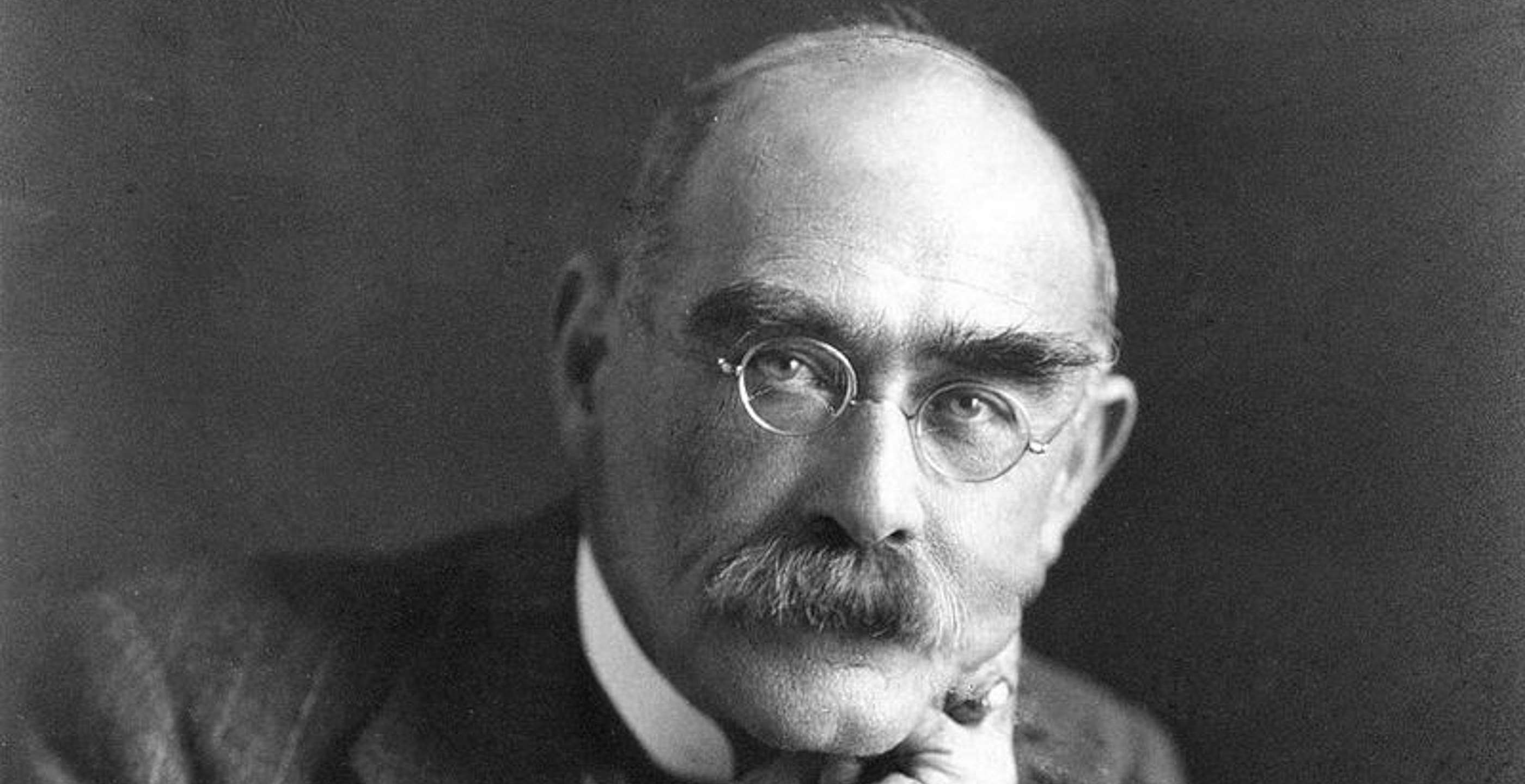

Rudyard Kipling’s famous line “The Colonel’s Lady and Judy O’Grady are sisters under the skin” does not even begin to convey the complex, harrowing lives of these courageous women.

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 14th June 2024