The mortal remains of monarchs of all people would seem most likely to receive respectful treatment after death. Yet this isn’t always the case. Notorious examples include the treatment of William the Conqueror’s corpse, and the strange fate of the severed head of James IV of Scotland. The remains of Charles I were placed hastily in the underground vault presumed to contain the bodies of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour at Windsor. He is there to this day, the prestigious new mortuary planned by his son Charles II never having materialised.

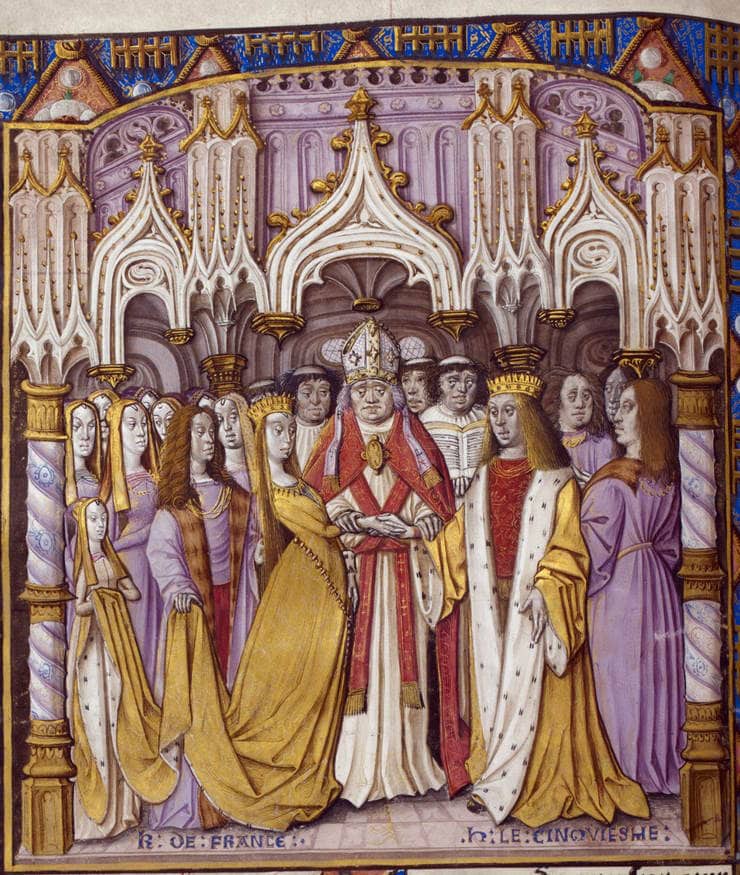

The body of Catherine de Valois (1401 – 1437), wife of England’s famous warrior king Henry V, was subject to one of the strangest and most perplexing afterlives of all royals. Daughter of Charles VI of France, Catherine was expected to play her part in a strategic alliance through marriage, as were all royal daughters. As wife of Henry V, Catherine would seal a cordial relationship between France and England. This had also been expected of her older sister Isabella, who was married to Richard II while Isabella was still a child. Catherine might have paused to reflect that alliance hadn’t exactly been ideal.

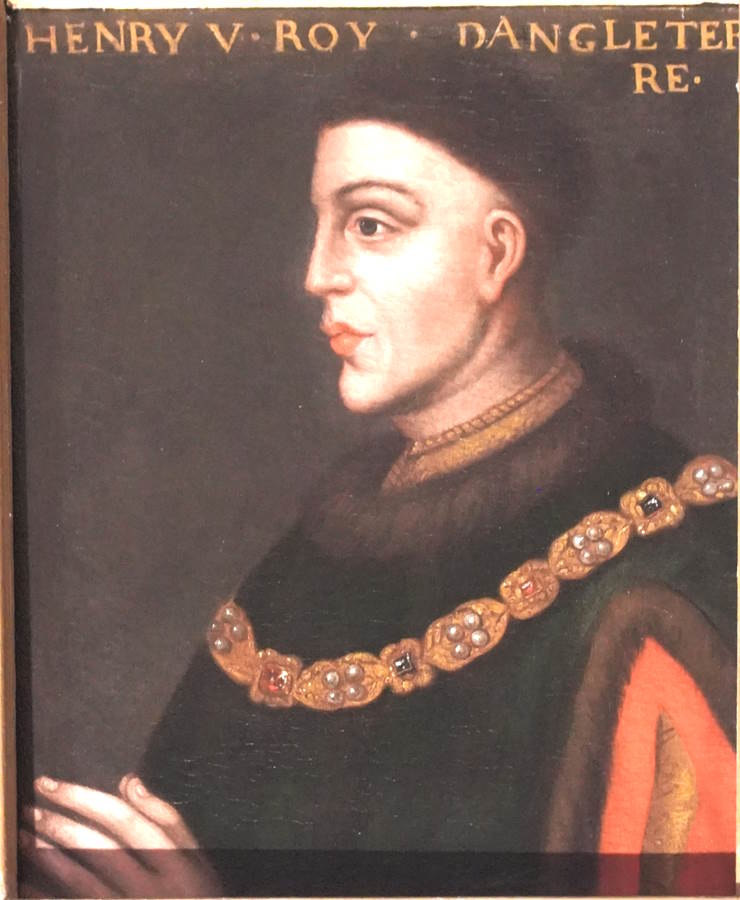

Rather than ushering in a new era of peace and unity between the two countries, and bringing to an end the war between them, the aftermath of the brief marriage between Catherine de Valois and Henry V marked the beginning of a new period of conflict. Although the match between the two had been discussed almost from the moment of Catherine’s birth, Catherine and Henry were to be married for just over two years. The wedding was celebrated in 1420 with the signing of a peace agreement known as the Treaty of Troyes. Yet Henry’s campaigning in France was not over, and he returned there, to fall ill and die in August 1422, never having seen his baby son, the future King Henry VI. Catherine’s father Charles VI died soon afterwards, leaving her in a theoretically powerful, yet in fact vulnerable position.

The relationship between Catherine and Henry seems to have been a genuinely caring one. Their son was heir to both France and England. Catherine was still young and might be expected to marry again. There would be no shortage of suitors, many of whom would be thinking about vicarious power, if not having an eye on the throne itself.

One of these potential suitors was her cousin-in-law, Edmund Beaufort, Count of Mortain. Catherine’s brother-in-law, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, was strongly opposed to this match, and ensured that if she married without the king’s consent, her future husband would lose all his property and goods. As young Henry VI’s guardian, Gloucester was powerful and could control Catherine’s marriage prospects until Henry VI came of age.

Events took an extraordinary turn when Catherine began a relationship with the Welshman Owen Maredudd Tudor. This young man had been in the household of her husband as a servant to Henry V’s steward. He appears then to have become steward for Catherine’s household, which co-existed with that of her son, who was still a minor. Catherine became pregnant, and later married Tudor, having three known sons with him, one of whom, Edmund, was the father of the future King Henry VII. Thus, Catherine became the ancestor of two royal dynasties. Her son Henry VI was accepting of her second marriage, but the stage was set for the conflict between Lancaster and York.

After Catherine’s first husband Henry V died, his body was embalmed and kept in Rouen Cathedral. Subsequently returned to Dover, the body was then borne in solemn procession to St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Then the coffin, with Henry’s effigy on top, was taken to Westminster Abbey. Four horses drew the funeral bier right into the nave, as close as possible to the location of the chantry chapel he had ordered for himself. This was only completed in 1431. It was a fine memorial, protected by railings and grating and uniquely bearing the arms of England and France. Henry’s funeral effigy subsequently disappeared, though a new one was made in 1971.

When Catherine of Valois died in 1437, she received an equally respectful and solemn funeral with a painted wooden funeral effigy robed in magnificent fabrics and fur. Her coffin was placed in the Lady Chapel of Westminster, and not next to that of her first husband, because of her remarriage. And this is where her corpse’s strange, even bizarre, afterlife, really began.

Catherine’s grandson Henry VII, ultimate victor in England’s Civil War, had big plans for the remains of his ancestors, and for Westminster Abbey. The plans included the demolition of the old Lady Chapel and the construction of a new one. The focal point in this chapel would be the body of Henry VI, who had received the status of a popular martyr since his death. Henry VII hoped that Henry VI would be sanctified and petitioned the Pope to canonise his relative.

Henry VII intended to be buried in the new Lady Chapel himself, along with his wife Elizabeth of York. In conflict for decades in life, the Yorkists and Lancastrians would be united in death under the approving otherworldly gaze of Henry VI, whose body was to be removed from Windsor and relocated in this new hallowed ground, in an impressive new memorial.

Work on the Lady Chapel had revealed the interment of Catherine of Valois. Henry VII removed the coffin and its remains and placed it in a temporary location while the work was completed. Henry certainly intended his grandmother to have a proper burial – eventually. After all, she was mother of Henry VI, who was going to take a ghostly proprietorial role in the new chapel. Henry VII’s grandmother Catherine was going to be there too. He was going to get round to it, just as he was going to get round to the translation of Henry VI’s remains. But you know, what with one thing and another, all those kingly duties and dealing with the death of heir Arthur and then that troublesome young future Henry VIII – it never happened.

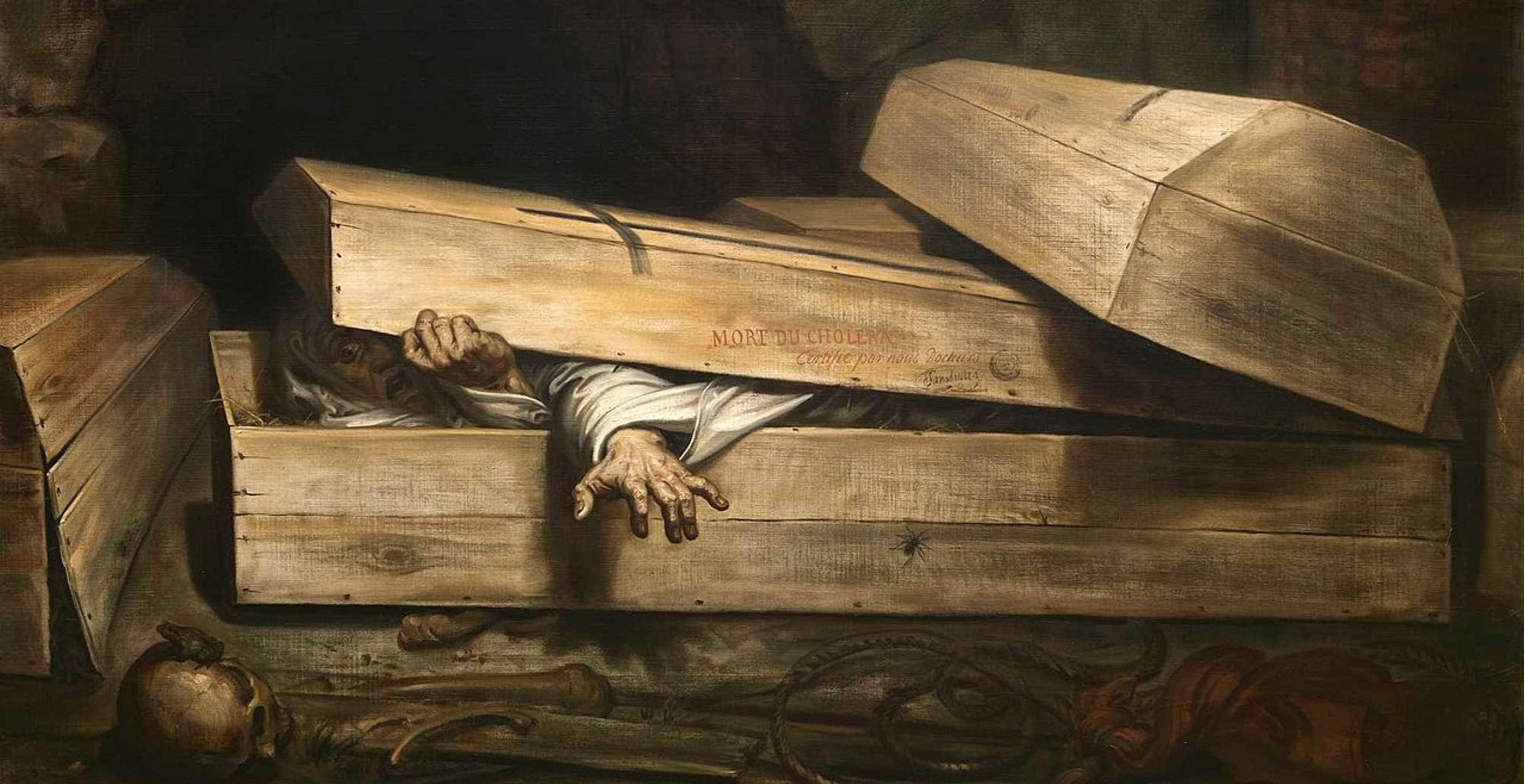

At some point between 1502 and 1509 Catherine’s body, in a shabby and battered wooden coffin, was placed – one almost thinks “plonked” – within the precincts of the magnificent tomb-memorial of her first husband Henry V. The coffin was falling apart to the extent that half of the lid had disintegrated, revealing the upper part of Catherine’s body. And there it remained for around 280 years.

No one seems to have considered it in the least odd to treat the remains of a queen like an odd item turned out of a half-tidied kitchen drawer. However, surely the contrast between the damaged coffin and its pitiful exposed occupant, and the magnificent monument of her warrior king husband, must have occurred to some observers. There were plenty of them too in later years, squinting and gawping at the queen through the grill of the memorial.

And there stayed Catherine de Valois, daughter, wife, mother, and grandmother of kings, on and on through reign after reign. Henry VIII, Edward, Mary, Elizabeth, James, and Charles I came and went, and not one of them did anything about their relative’s corpse. The queen’s remains received passing recognition from the chroniclers Raphael Holinshed and John Stow, her accent was mocked by Shakespeare, and she was depicted as the nudge-nudge merry widow in more than one account. Thieves even broke into Henry V’s memorial and stole items made of gold from it, with the queen’s corpse still lying exposed there.

If her spirit was still in the vicinity, it seemed there would be little left to shock her. Yet on Shrove Tuesday, 23 February 1668 (1669 by our reckoning), Samuel Pepys noted gleefully that he had been allowed to smooch her corpse. He took his wife and servants to Westminster Abbey:

“… and there did show them all the tombs very finely, having one with us alone, there being other company this day to see the tombs, it being Shrove Tuesday; and here we did see, by particular favour, the body of Queen Katherine of Valois; and I had the upper part of her body in my hands, and I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this was my birth-day, thirty-six years old, that I did first kiss a Queen.”

It’s perhaps as well there was no contemporary Shakespeare to produce some dire dialogue for this gruesome encounter. Thus, subsequent generations have been spared the pain of Catherine’s ghost murmuring “Ooh la-la Monsieur Pepys! You naughty, naughty boy!”

In the following century, Catherine’s corpse suffered even greater indignities as it became more of a curiosity and a tourist attraction. The memorial must have been open to visitors, for her body was badly mauled by Westminster schoolboys. Then finally, in 1778, Dean Thomas arranged for the queen to be removed to the safety of the newly renovated vault of the powerful Percy family, in which were interred the Dukes and Duchesses of Northumberland.

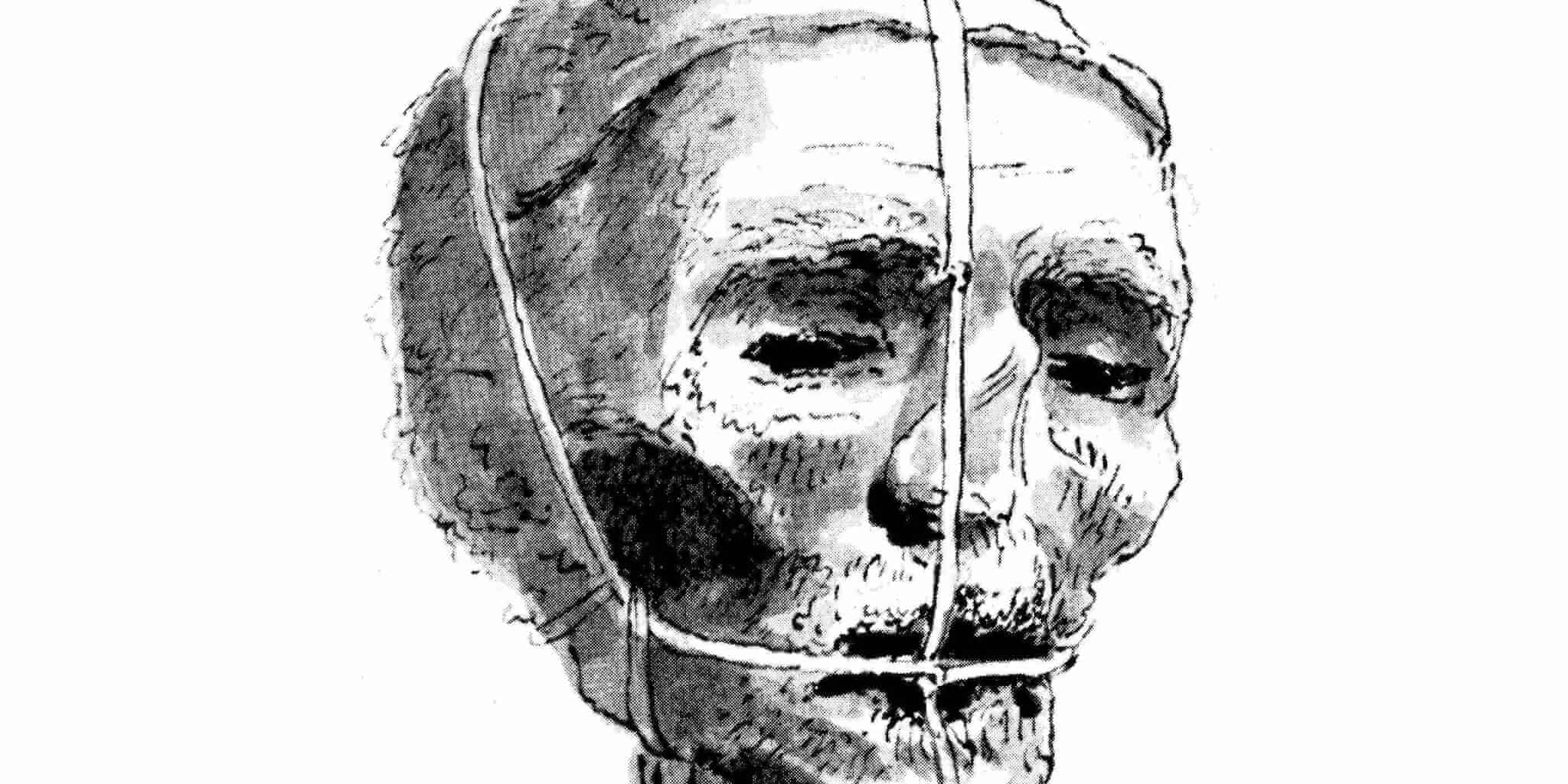

It wasn’t until the reign of Victoria, however, that Catherine went to her final resting place. In 1877, Sir George Gilbert Scott recommended that she should be properly interred next to her husband, in a specially designed space within the chapel’s altarpiece. Exhuming her remains once more, the investigators found a sorry jumble of bones with numbers missing or damaged.

Dean Stanley of Westminster concurred with Scott, and Catherine’s body was respectfully laid to rest under the stone slab that had once topped the altar in Henry’s memorial. The translation of the Latin memorial to the queen reveals that “long cast down and broken up by fire, rest at last, after various vicissitudes, finally deposited here by command of Queen Victoria, the bones of Catherine de Valois, daughter of Charles VI, King of France, wife of Henry V, mother of Henry VI, grandmother of Henry VII, born 1400, crowned 1421, died 1438.”

One can almost hear Catherine’s ghost sighing as she points out, “Actuellement, it was 1437. But at least you got my name right.”

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 19th February 2024