Cornwall, though officially part of England, has a special status in that it considers itself to be quasi independent. Visit the most south-westerly county and you’ll find the famous black and white St Piran’s flag, not the cross of St George, waving in shop windows and stuck on car bumpers. There is a proud tradition of Cornish distinctiveness and independence. Tell a Cornishman he’s English and you’ll probably be told to go back to where you came from.

The Cornish rebellion of 1497 epitomises Cornwall’s sense of identity and autonomy, and helped to establish the anti-English sentiment that has continued to this very day.

With the ascension to the throne of Henry VII in 1485 and the new Tudor dynasty came increased centralisation of government and affairs. At this time Cornwall was a distinct region inhabited by Celtic peoples, akin to the Welsh and Bretons, and many of these peoples spoke Cornish rather than English.

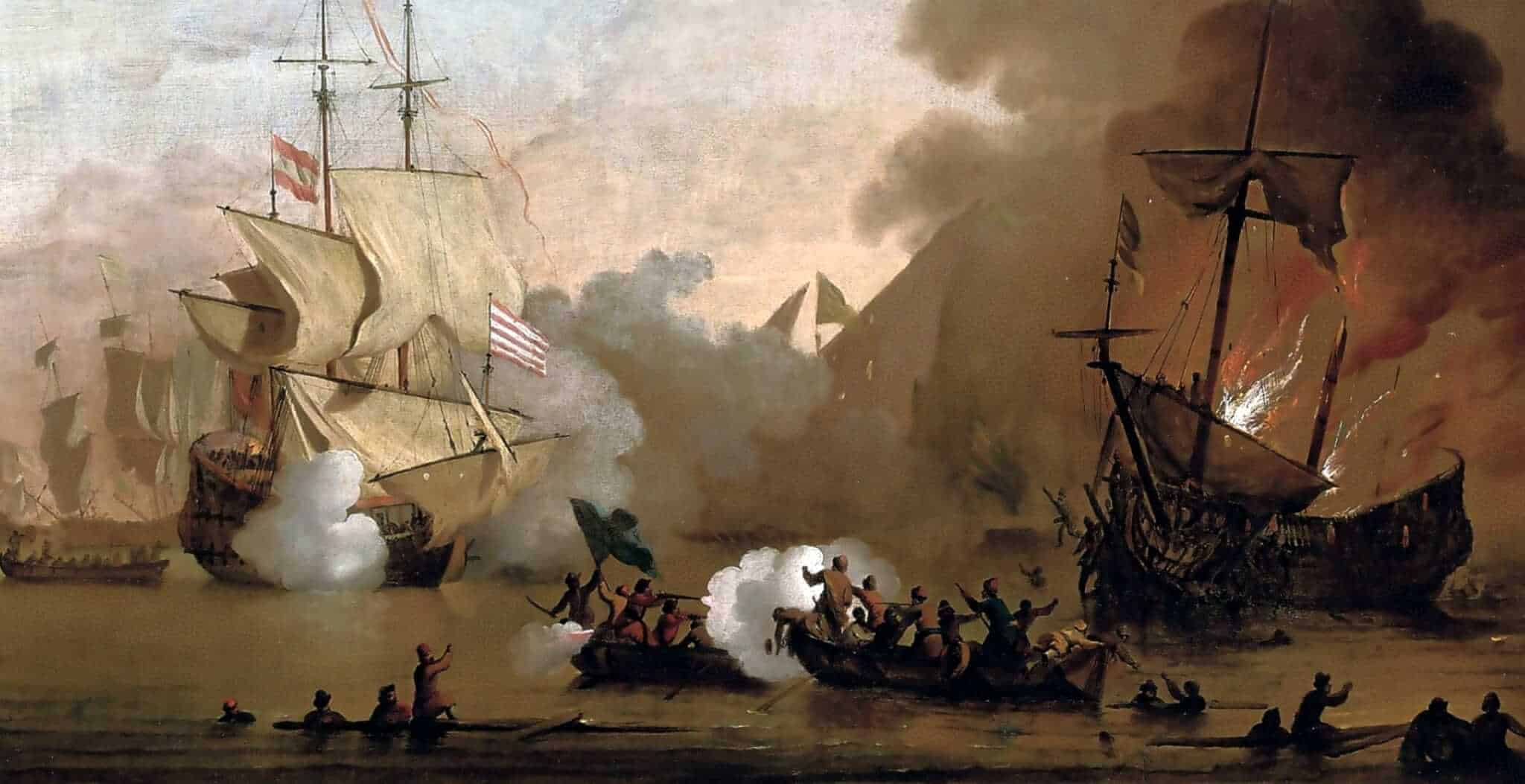

In 1497 Henry demanded exceedingly high taxes from the Cornish to wage war in Scotland against an imposter to the throne: Perkin Warbeck. Warbeck claimed to be Richard Duke of York, one of the ‘Princes in the Tower‘, who had a rightful claim to the English throne. In reality however he was not. Rather, he was an example of the hangover from the Wars of the Roses, with the Yorkist descendants bitter about losing their claims to the throne. James IV of Scotland however welcomed him as the rightful King of England, wishing to undermine Henry and the English, prompting Henry to declare war. The Cornish however felt this was completely unjustified as Scotland was no threat to them, it being over 500 miles away. However this was to become Tudor policy, imposing taxes upon subjects all over the country to finance foreign wars. This was effectively the beginning of governmental centralisation, and it still continues today. However it was not just taxes that provoked the Cornish to rebel.

Tin mining was of great economic importance for Cornwall, so much so that it had its own separate government institutions: Stannary Parliaments. Stannary Law in fact is one of the oldest incorporated laws in England, and it gave special privileges to Cornwall to reflect just how important tin mining was to the region. This gave Cornwall its own sense of autonomy and identity. However in 1496 Henry VII suspended these privileges and issued new tin mining regulations, once again in the attempt to undermine Cornish autonomy and further Tudor centralisation. This was the final straw for the Cornish, as their quasi-autonomous status given to them via the Stannary Parliament was now lost.

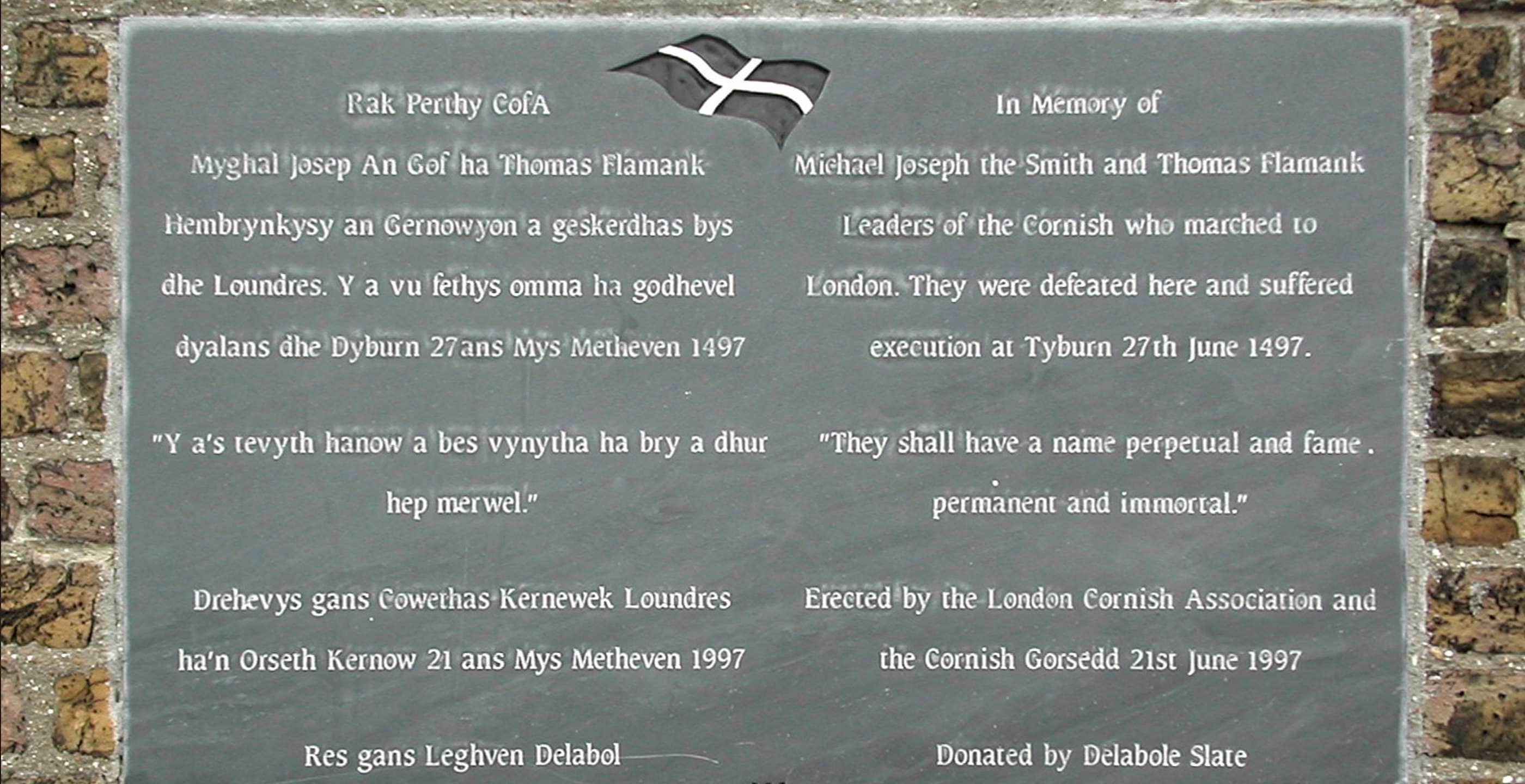

The rebellion started on the Lizard Peninsula and by the time they reached Devon, some 15,000 men were involved. During this time King Henry was in the north attempting to wage war against Scotland, however he was forced to retreat due to the danger the rebels posed. He assembled an army of some 25,000 men to battle the Cornish rebels. The rebels had picked up support on their march from Cornwall, however they were never efficiently organised and lacked both proper leadership and proper arms in comparison to the King’s forces. They did however manage to march all the way to London, and the two sides met at the Battle of Blackheath on 17th June 1497. The Cornish rebels, led by a blacksmith and lawyer, were easily defeated by the King’s forces at the battle just outside London, in what today is Deptford. It is thought that the residents of London took up arms and barricaded the walls of the city in order to keep out the rebels. In total, roughly 1000 rebels were killed, with the number of royal forces killed unknown.

The battle though was not fought in vain, as Henry restored the Stannary privileges the Cornish so desperately wanted and never imposed such high taxes on the Cornish again. In 1997 Cornwall marked the 500th anniversary of the rebellion by recreating the original march. The “Keskerdh Kernow” march, Cornish for “Cornwall marches on”, shows how the rebellion played a huge part in the foundation of Cornish identity and is still in the minds of the Cornish today. Plaques and statues of the leaders of the rebellion were also unveiled in commemoration.

Oliver Coops, from London, History student at the University of Exeter. Great passion for history and politics, with interests in Tudor and Celtic history.