On a dripping July morning in 1543, the much-married, increasingly volatile King Henry VIII married his final wife, Katharine Parr, at Hampton Court Palace.

This was to be Henry’s sixth marriage and Katharine’s third, and was intended to be a private affair, absent of the pomp and circumstance with which Henry Tudor’s reign had begun. At a stroke, Katharine’s new title of ‘Queen’ elevated the Parr family into the highest echelons of the glittering, mercurial Tudor world. It was here that the Parrs would remain comfortably established for over a decade – a triumphant feat for a divisive family at the nucleus of a court famed for its violence, treachery, and acts of political subterfuge.

By Tudor standards, Henry’s choice of bride was not particularly ‘young’. Nor was she, by then thrice married, the ‘maid’ Henry would have energetically pined for in his heyday (the imitable Anne Boleyn was in her early twenties when Henry split from the Papacy and installed himself as head of the Church of England in order to marry her.) Katharine was some twelve-years older than Henry’s most recent wife, Catherine Howard when she married the King, at which point Henry was thought to have ‘effectively given up’ hopes for love or a second son. By the early 1540s, the King found himself in the slow, agonising, and malodorous segue of death (though to avouch that His Majesty was, in fact, ‘dying’ was strictly treason.) Henry weighed close to four-hundred pounds, suffered from pus-filled leg ulcers from previous jousting injuries, and was rapidly deteriorating into a state of paranoia, depression, and anxiety.

Withdrawn from public view and from the idea that he would ever find an ‘untainted’ bride, Henry’s growing infirmity inspired feelings of insecurity in both the fledgling Tudor dynasty and his own marital virility.

On the contrary, Katharine was described by her contemporaries as vivacious, astute, and of ‘lively and pleasing appearance.’ At thirty-one, Parr was fashionable, a patron of various arts made popular by the English Renaissance, scholarly, and attractive. Much like the King himself, she was said to have pale skin and the quintessential auburn hair of the Tudor age, and is thought to have been of a tall, graceful build, with leaden-grey eyes. A naturally outspoken woman, Katharine would cement her place in history as the first English queen to publish literature in her own name, and her true-blue devotion to the ‘New Religion’ emerging from the English Reformation nearly cost Katharine her life (though she managed to flatter the King out of a impending arrest).

As Queen, Katharine displayed a natural ability to execute the more ‘feminine’ duties of a Henrician consort, and wielded considerable sartorial influence. Similar to Henry’s second queen, Anne Boleyn, Katharine took a keen interest in her style of dress and commissioned John Scut (the tailor who had served all of Henry’s previous wives) to embellish her natural sense of occasion. She was said to be fond of ostentatious accessories, and owned an impressive number of caps, rubies, and pearls. Henry’s final Queen was often kitted out in cloth of gold, crimson, eye-catching brocade, and royal purple for special occasions, which finely displayed Katharine’s innate elegance and exhibited outward majesty.

Additionally, she shared in her husband and stepdaughters’ passion for music and dancing, and her household was said to have included a proficient consort of Italian viols.

Katharine’s personal accomplishments belie the notion that she was sought out by the rapidly deteriorating Henry on the grounds of her ‘nursing abilities.’ Rather unfortunately, Katharine has gone down in history as her husband’s devoted minder and nursemaid, rather than his wife, an idea that almost certainly stems from the work of the Victorian proto-feminist Agnes Strickland. King Henry’s impressive retinue of physicians waiting upon him hand and foot would have certainly alleviated the need for a wife to tend to each of his liverish needs. Katharine, rather than acting as an attendant to Henry’s infirmity, would have therefore been expected to live up to the considerable expectations of ‘queenly dignity’ exemplified by Henry’s mother, Elizabeth of York, and continued by his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

The necessity for a queen to showcase the Tudor’s might and unity became particularly important as Henry decreased his public outings and retreated, tormented with pain and anxiety, into his private apartments. At so advanced an age and in a state of physical and mental decline, it is far more likely that in Katharine, Henry saw the possibility of a comforting companion to live out his final years with: an intelligent, charismatic, loyal, and attractive woman who shared in his abiding passion for music, theology, debate, moral rectitude, and royal ceremony.

Whatever the reasons behind their union, the King eventually succumbed to his illnesses in January 1547, leaving Katharine a wealthy widow. The dowager queen shocked the court when she impetuously married the new King’s uncle, Thomas Seymour, only a few months after Henry’s death. It is entirely probable that Thomas had already been courting Katharine Parr when she caught Henry’s eye, and was invested with a position abroad to divert his attention elsewhere when it became clear that Henry intended to have Katharine for himself.

Disgruntled, but never thwarted, Seymour persisted in his indomitable search for a rich, well-connected wife, and may have considered Mary Howard, the widow of Henry’s illegitimate son, or one of the King’s own daughters as potential brides. Whatever his ambitions, Katherine threw caution to the wind and married Thomas, her fourth and final spouse, in May 1547, only five months after the King’s death. Soon after, at the age of thirty-five, Katharine fell pregnant.

Katharine’s pregnancy was a strenuous one: it was during this period that Thomas Seymour’s roving eye turned to Henry’s youngest daughter, the Lady Elizabeth. As Katharine was thought to be dangerously old to be having children, Seymour might have been hedging his bets in setting his cap at Elizabeth: should anything happen to his wife, he may have thought to take the teenage Elizabeth as his bride. The former princess’ governess, Kat Astley, appeared to facilitate Seymour’s access to her charge with this in mind. Seymour was openly seen in Elizabeth’s chambers before she had risen for the day, dressed only in her nightgown, and holding her in his arms during his wife’s pregnancy. Racked with debilitating symptoms, Katharine was confined to her apartments as her husband continued to pay court to her stepdaughter.

At the end of a scorching English summer, on 30 August 1548, Katharine Parr went into labour at Sudeley Castle. She gave birth to a girl, Mary, who was perhaps named so to soften the Lady Mary’s anger at Katharine for ‘shaming’ her late father. Katharine appeared in high-spirits, though privately she confessed ‘she did fear such things in herself, that she was sure she could not live.’ Only days later, Katharine’s fatal premonitions were realised. She became ‘suddenly feverish,’ displaying the telltale signs of puerperal fever. It was then, in Katharine’s delirium, that her opprobrium and anger toward Seymour bubbled to the surface. ‘I am not well handled,’ she cried, railing that Seymour ‘careth not’ for her, and stood ‘laughing at my grief.’ Seymour attempted to calm her, but to no avail. The more he attempted to mollify Katharine, the more she ‘dealt with him roundly and shortly.’

The former Queen died in the early hours of 5 September, harrowed with anguish and humiliation. She was interred on the same day in a chapel on the grounds of Sudeley Castle with bizarre haste, deprived of the time-honoured rituals befitting a woman who had once been Queen of England. Katharine was not afforded a funeral effigy, nor a procession of mourners, nor did she lie-in-state, surrounded by thousands of wax candles, as her predecessors Catherine of Aragon and Jane Seymour had done. Her sole legacy to the world, Mary Seymour, passed into the hands of a noblewoman, and most likely died in infancy.

Katharine Parr’s death would appear to mark the end of a fascinating woman and of an equally thrilling tale – marked by royal intrigue, romance, and political gambits – and yet her story was determined not to end here. In fact, the Queen’s body would undergo a dramatic expedition for another three hundred years, resulting in one of the most chilling afterlives of any queen consort in British history.

On the day of her death, Katharine Parr’s body was hastily sheathed in waxed cloth and wrapped tightly with sheets of lead, impenetrable to the various elements of the idyllic Cotswolds. After a short, albeit solemn prayer was delivered over the body, Katharine’s body was interred and forgotten for centuries.

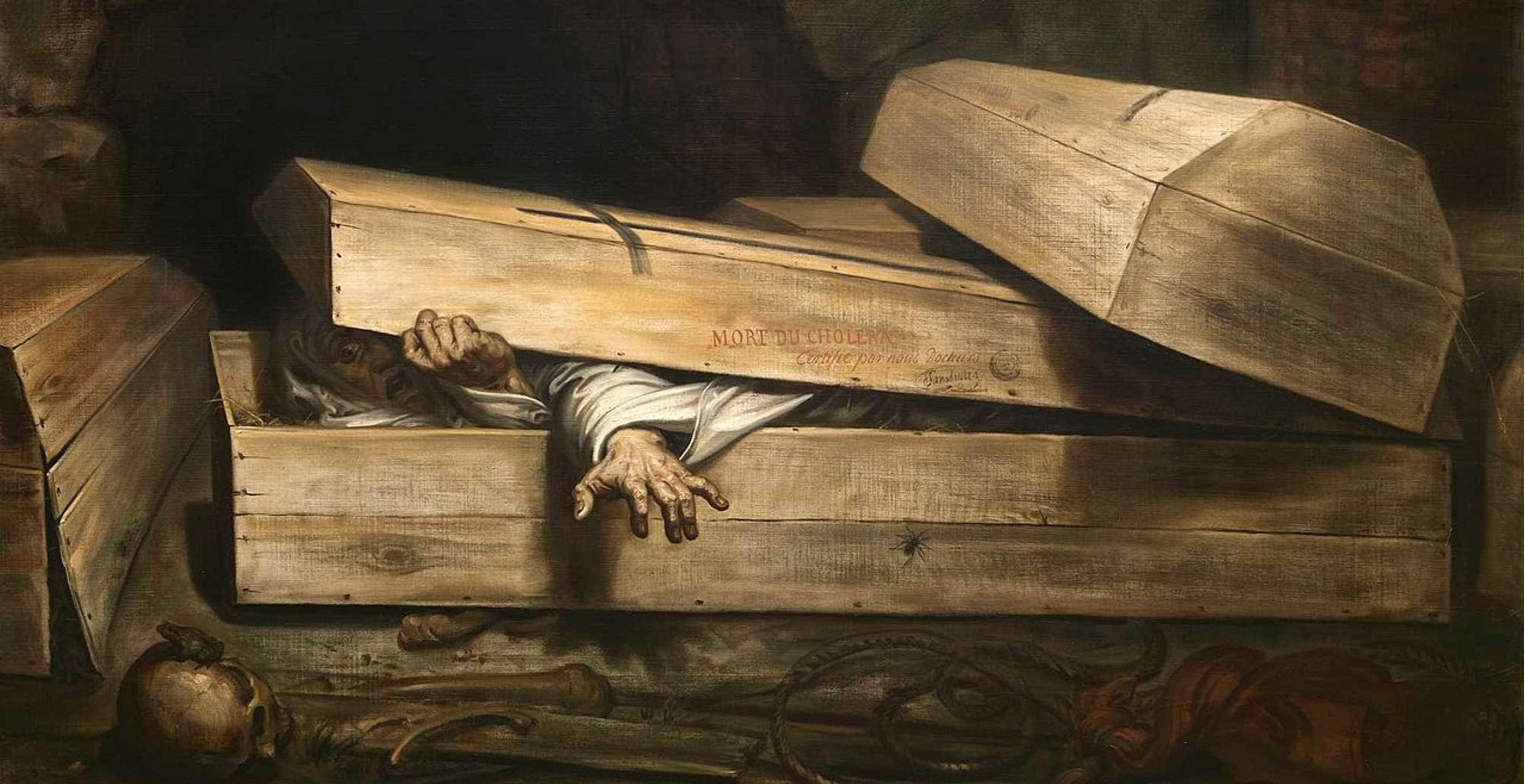

The Queen’s burial site would eventually fall into ruin: the chapel’s roof was at one point removed, and by the mid-18th century, nature’s rot had set in. In 1782, however, a local resident named John Lucas would stumble upon Katharine’s coffin, found buried at a depth of two feet. He pried open the Queen’s tomb, made a small, curious incision in the body’s waxed cloth wrapping, and miraculously found Katharine’s flesh still ‘white and moist’, and strikingly lifelike. Lucas described her appearance as unchanged – another tremendous feat, considering that Katharine had died over two centuries prior. He snipped a few pieces of Katharine’s hair, a swatch of fabric from her gown, and snagged a tooth from the Queen (which is now located, alongside various other relics, in the Sudeley museum). Lucas, having concluded his poking around of the site, left Katharine to rest in peace once more. Nevertheless, his discoveries would have dire consequences for the late Queen – they soon attracted a cult of well-bred ladies to flock to the tomb of Henry VIII’s final wife, marvelling at the Queen whose physical form, both in life and in death, was viewed as a tangible, powerful, and sacred extension of the ‘body politic.’

Only a year later, in the summer of 1783, explorers returned to the site of Katharine’s burial. ‘On being told what had been done the year before by Lucas,’ one witness wrote, ‘I directed the earth to be once more removed to satisfy my own curiosity.’ The only difference that this witness discovered was that Katharine’s body had begun to emit a foetid odour, and the flesh where Lucas had made an incision was brown, in a state of ‘putrefaction in consequence of the air having been let in.’ Deterred by the stench of the corpse, the witness concluded his excavations and decided that a stone slab should be placed over the grave to ‘prevent any future and improper inspection.’

Katharine’s coffin would be again reopened in 1784 by ‘some rude persons,’ who collected the body and left it exposed on a heap of rubbish, until the ‘parish vicar procured its re-interment.’ Again in 1786, Reverend Nash ‘made a scientific exhumation of the body,’ and described Katharine’s face as ‘totally decayed, the teeth sound, but had fallen out, and the hands and nails were entire, but of a brownish hue.’

The Reverend wrote that he wished that ‘more respect were paid’ to the remains of the Queen, hoping that she would someday be ‘decently buried’ so that her body could at last rest in peace. Instead, the dilapidated chapel where Katharine had been buried had been misappropriated into a shed for rabbits, ‘which make holes and scratch very irreverently about [her] royal remains.’

Throughout the final decades of the 18th century, Katharine’s coffin would be opened several more times. In the 1790s, a pair of drunken gravediggers attempted to satisfy the Reverend’s desire by gouging out a new grave for Katharine, though they later buried her upside down. Strickland claims that the gravediggers abused the corpse, though she is vague on the issue – to describe what they actually did to Katharine’s body was too horrific to mention. Certain sources suggest that the bacchanalian pair pulled out Katharine’s hair, knocked out several of her teeth, wrenched off her arms, stabbed her through the chest with an iron bar, and pilfered the Queen’s body parts to sell as souvenirs. In any event, Katharine’s remains had become a commodity: a vestige of the glories, and barbarity, of the Tudor age.

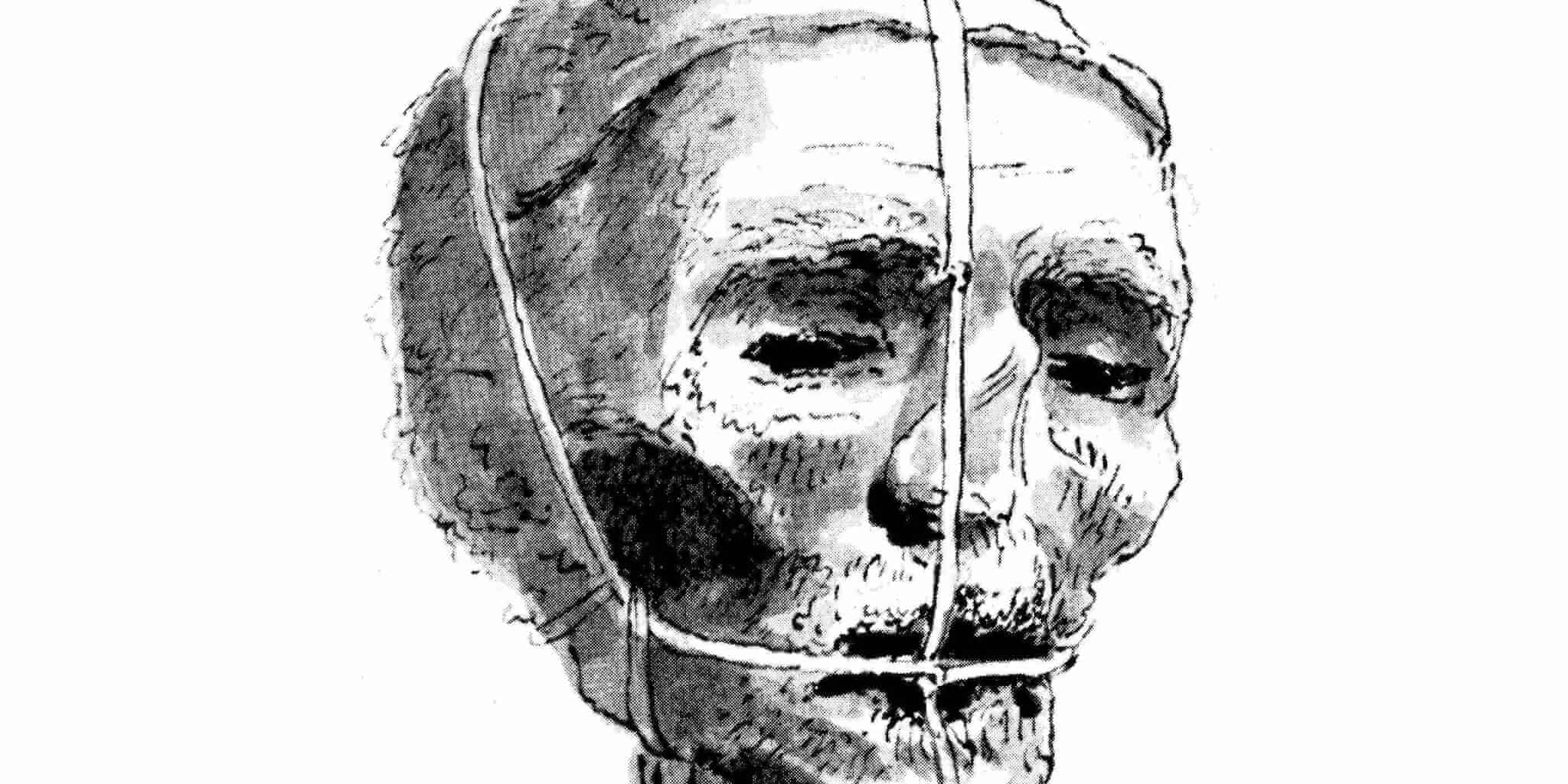

Two decades later, in 1817, Katharine’s tomb would be disturbed and disinterred for a final time. The rector of Sudeley had resolved himself to launch repairs of the chapel, determined to find the place where the pie-eyed gravediggers had ignominiously dumped her body. ‘After considerable search,’ the explorers found Katharine, ‘bottom upwards in a walled grave,’ and then moved her to a separate vault. To the great disappointment of all, the witnesses found nothing but the skeletal remains of the Queen, together with a few shreds of cloth, and a small quantity of ‘dark-colored’ hair. At last, Katharine’s perfectly preserved body had succumbed to nature’s withering course. It is reported that an ivy wreath had wound itself about Katharine’s head, forming a ‘green sepulchral coronet’ over the Queen’s skull.

The magic of Katharine’s body dissipated with the advent of the 19th-century. In 1861, the remains of Queen Katharine were collected and interred ‘with pious care’ elsewhere. By then, however, her skeleton had been reduced to ‘a little brown dust.’ Her fragmented remains were finally placed in St. Mary’s Church at Sudeley Castle, in what is now the finest coffin of any of Henry’s wives. To this day, Katharine lies peacefully within a neo-Gothic tomb, her marble hands clasped in reverent and, at last, eternal prayer.

Sudeley Castle – where Katharine’s body has rested since her death some 470-years ago – remains home to rare copies of books owned and written by the Queen, as well as her love letters made out to Thomas Seymour, and eye-witness accounts of the discovery of her burial site. The jewels and magnificent gowns Katharine once wore as Queen were confiscated by the crown and sent to the Tower of London after Seymour’s execution in 1549.

Daniella Novakovic is freelance writer, specialising in the Early Modern Period, and a life-long student of the Tudor Age. She is the author behind @earlymodernhistories on Instagram.

Published 8th November 2022