Edward the Confessor, known by this name for his extreme piety, was canonised in 1161 by Pope Alexander III. He became one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England, reigning for an impressive twenty four years from 1042 until 1066.

The last king of the House of Wessex was born in Oxfordshire at Islip, son of King Ethelred “the Unready” and his wife Emma of Normandy. He was the king’s seventh son and the first of Ethelred’s new wife, Emma. Born around 1003, his childhood was marred by the continuing escalation of conflict from Viking raids which targeted England. By 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard had seized the throne, forcing Emma of Normandy to flee to safety with her sons, Edward and Alfred.

He spent much of his early life living in exile in France, his family driven away by Danish rule. When his father Ethelred passed away in 1016 it was left to Edward’s half-brother, known as Edmund Ironside to continue to fight against Danish aggression in England, this time facing the imposing threat from Sweyn’s son, Cnut.

Unfortunately Edmund did not last long, as he died later that year, allowing Cnut to become king with Edward and his siblings forced into exile. One of his first acts as king was to have Edward’s elder half-brother Eadwig killed, leaving Edward the next in line. Edward’s mother married Cnut in 1017.

Edward subsequently spent his formative years in France although he vowed he would return to England one day as the rightful ruler of the kingdom. It is believed he spent much time in Normandy where he lived the lifestyle of nobility, whilst hoping on various occasions to seize an opportunity to ascend to the throne. He even signed charters as King of England and received support from a number of people who gave his royal entitlement their personal backing.

One of these figures was the Duke of Normandy, Robert I who in 1034 attempted an invasion of England in order to restore Edward to his rightful position. Furthermore, other supporters of his cause included figures in the church. It was during this time that Edward appeared to turn to religion and develop a strong sense of conviction, a piety he would carry with him throughout his life and for which he would ultimately become well-known.

Unfortunately for young Edward, despite receiving support, his chances of assuming the throne looked particularly thin, especially due to his mother, Emma of Normandy, who greatly favoured her other son, Harthacnut, son of Cnut the Great. Emma’s ambition for her Danish son usurped Edward’s chances as king, but for how long?

By 1035, Cnut had died and his son with Emma, Harthacnut assumed the role as King of Denmark. At the time he had been largely preoccupied with events in Denmark and had failed to lay claim to the throne in England. This left the royal role vacant for his elder half-brother Harold Harefoot who stood in as regent. Meanwhile, Harthacnut’s mother Emma kept Wessex on behalf of her son.

A year later, probably fearing their mother was losing her grip on power at the hands of Harold, Edward and Alfred received invitations to go to England from Emma. Unfortunately for Alfred this visit would seal his demise, as he was quickly captured by Godwin, the Earl of Wessex who handed him over to Harold where his grisly fate was met. Alfred suffered a dreadful death, blinded with red-hot pokers; he would later die from his injuries. Edward justifiably would bear a grudge and a seething hatred for Godwin and later banish him when he became king.

Edward quickly returned to Normandy. In the years that followed, Emma would find herself expelled by Harold and forced to live in Bruges, begging Edward for help in securing Harthacnut’s ascendancy. Edward simply refused and it was not until Harold’s death in 1040 that Harthacnut was able to take the throne in England.

By this time his half-brother, now King of England invited Edward to England, knowing that he would be the next in line to the throne. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle subsequently records Edward’s swearing in as king upon the death of his brother. With the support of the powerful Earl of Wessex, Godwin, Edward was able to succeed the throne.

His coronation took place at Winchester Cathedral on 3rd April 1043. A jubilant atmosphere welcomed the Saxon king back to his kingdom. As king he found it prudent to deal with his mother who had practically abandoned him in his time of need and favoured his sibling. In November the same year he saw fit to deprive her of her property, an act of personal vengeance against a mother he felt had never really supported him. She died in 1052.

During his reign Edward would manage affairs in a fairly consistent manner, however despite this he was faced with some skirmishes occurring both in Scotland and Wales. Edward managed a forceful campaign and in 1053 ordered the assassination of the southern Welsh prince Rhys ap Rhydderch. Furthermore, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn emerged in 1055 and declared himself leader of Wales but was forced back by the English, who forced Gruffydd to swear an oath of loyalty to the king.

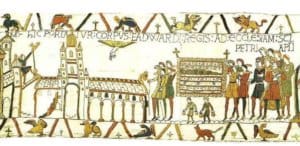

Meanwhile, Edward’s leadership continued to reflect his Norman background. One of the most tangible displays of Norman influence was the creation of Westminster Abbey. The project itself was executed in 1042 and was eventually consecrated in 1065. The building represented the first Norman Romanesque church and even though it was to be later demolished in favour of Henry III’s construction, it would play a major role in developing a style of architecture and demonstration of his links to the church.

Edward’s long time abroad and clear Norman style however did contribute to a growing atmosphere of resentment. In January 1045, Edward had sought to calm any conflict between himself and Godwin, the Earl of Wessex, by marrying his daughter Edith.

Unfortunately for Edward, his position was severely compromised by the power held by the earls, in particular Godwin, Leofric and Siward. In time the earls would grow increasingly irate at the clear demonstrations of Norman favouritism exhibited by the king.

The tension boiled over when Edward chose Robert of Jumièges as Archbishop of Canterbury instead of Godwin’s relative. The new Archbishop would later accused Godwin of plotting to murder the king. Edward would seize his chance to oust Godwin, with the help of Leofric and Siward and with Godwin’s men unwilling to go up against the king, he outlawed Godwin and his family, which included Edward’s own wife Edith.

Unfortunately the battle for power was not over yet for King Edward, as Godwin would return a year later with his sons having accumulated much needed support for their cause. Edward no longer had the support of Leofric and Siward and was forced to make concessions or fear civil war.

In the latter half of Edward’s reign the political picture began to alter and Edward was distancing himself from the political fray, instead engaging in gentlemanly pursuits after attending church every morning. The Godwin family would subsequently control much of England whilst Edward withdrew.

By 1053 Godwin had died leaving his legacy to his son Harold who became responsible for dealing with rebellion in the north of England and Wales. It was these actions that prompted Edward to name Harold as his successor even though it had already been established that William, Duke of Normandy would assume the throne. This inevitably led to conflict and chaos when Edward died on 5th January 1066. The issue of succession was a major contributing factor to the Norman conquest of England.

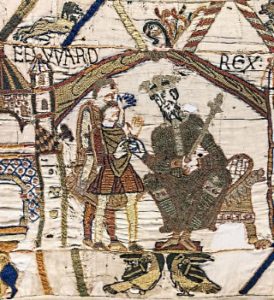

Edward the Confessor, one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings, has been historically preserved and depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. His legacy as a leader was mixed, damaged by infighting and attempts by others to seize power. Nevertheless, he brought with him a strongly religious influence, Norman-style administration and reigned for a long twenty four year period. He was later canonised and adopted as one of England’s national saints, with a feast day celebrated on 13th October in his memory.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.