Emily Davison, influential British suffragette, was born in South East London in 1872. She was a high achiever and won a scholarship to study literature at Royal Holloway College when she finished school. This was cut short, however, when her father died and her mother could no longer afford to pay the tuition fees. Emily became a teacher until she had saved enough money to finish her studies at London University, graduating with a BA. She later attended St Hugh’s College, Oxford for one term.

At this time, academia was a male dominated world and Emily developed strong opinions about the limited opportunities available to women in society.

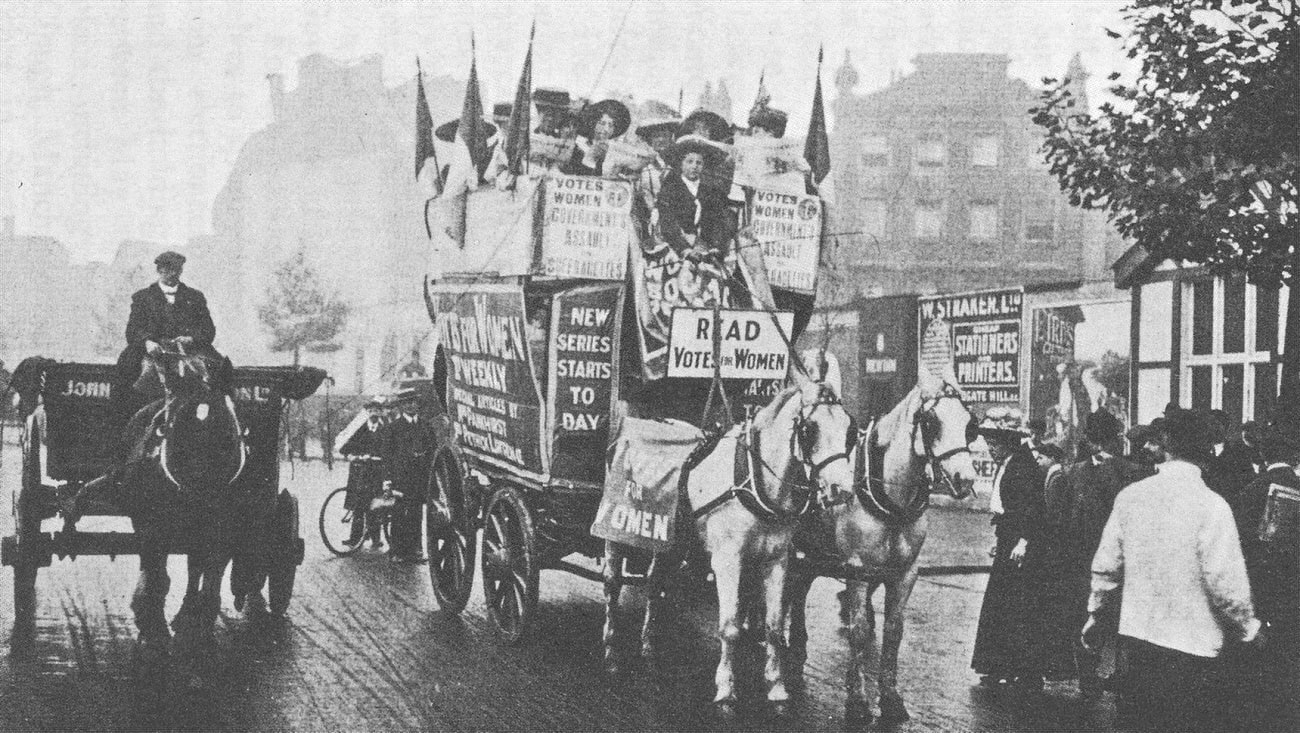

The Women’s Social and Political Unit (WSPU), founded by Emmeline Pankhurst, caught Emily’s interest and she soon became a radical member. A more militant offshoot of the original National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the WSPU expressed the view that by disallowing women the vote, the state was classing them as second-rate citizens.

Emily rapidly became head steward of the WSPU and gave up work to dedicate more time and effort to “the Cause”. She was quite the activist; Emily was one of the suffragettes who were found hiding in air ducts within the House of Commons, apparently just listening in to Parliament (she did this three times); she threw metal balls labelled “bomb” through windows and was sent to prison six or seven times in four years!

She was sent to prison twice in 1909, each time for two months, once for attempting to enter a room where the Chancellor of the Exchequer was delivering a speech and once for hurling rocks. Both of these trips to prison ended early when she went on hunger strike.

It wasn’t long before she was back in jail again however, this time for hurling rocks at the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s chauffeur driven car, each one tightly wrapped in Emily’s signature slogan, ‘Rebellion against tyrants is obedience to God.’

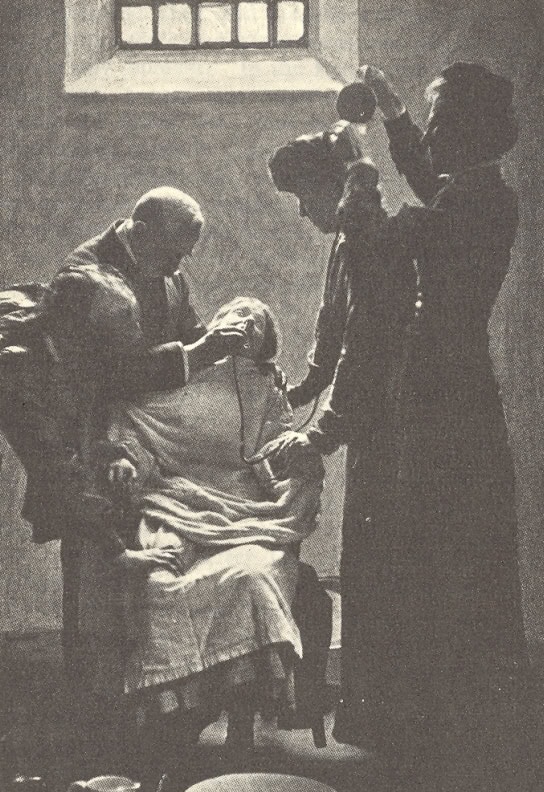

Once in Strangeways Prison, Emily resorted to hunger strike again; this time however, the authorities decided to apply force-feeding instead of early release. In response to this, Emily barricaded herself in her room. Her prison officer decided to flood Emily’s cell with ice-cold water in an attempt to force her out. Emily nearly drowned but was rescued just in time. The public were in uproar at this appalling treatment from the prison wardens and Emily, who took the case to court, was awarded forty shillings compensation.

This was certainly not the only time that Emily showed herself willing to die for the cause she dedicated her life to. She was jailed again for 10 months in 1912 for setting fire to London post boxes. During this time she again went on hunger-strike. The prison resorted to force-feeding again and, in protest to this, Emily threw herself from a balcony:

“I did it deliberately, and with all my power, because I felt that by nothing but the sacrifice of human life would the nation be brought to realise the horrible torture our women face. If I had succeeded I am sure that forcible feeding could not in all conscience have been resorted to again”.

This act raised questions with the authorities; they realised that women were willing to become martyrs in the name of the cause. This lead to the introduction of the Prisoners’ Temporary Discharge for Health Act which declared that prisoners could be released if they threatened hunger strike but arrested again when they had regained their strength. Emily suspected that if she died in prison, the authorities could cover it up as an accident, therefore if she were to become a martyr, it would have to be in public and she would have to be in full control of the incident.

The Epsom Derby, June 4th 1913

And what could be more public than the 1913 Epsom Derby? Thousands of people, including King George V and Queen Mary, thronged to the event. The King’s horse Anmer was one of the runners in that year’s Derby. And it was Anmer that Emily targeted.

Epsom racecourse is shaped like a horseshoe: the start is along a straight leading to a long corner that straightens out at Tattenham Corner before finishing down the straight in front of the Royal Box. The King’s horse Anmer was easy to spot among the other horses as the jockey, Herbert Jones, was wearing the King’s colours.

As the horses thundered around Tattenham Corner, Anmer was third from last. Emily had pushed her way through the crowds and slipped underneath the protecting rail. As Anmer came around this final corner, he could not avoid thundering into Emily as she stood in front of him, holding the suffragette flag close to her. Jones was thrown from his seat and the horse fell, getting up again and finishing the race alone. Jones suffered broken ribs, bruising and concussion. Emily was rushed into hospital but had received fatal internal injuries and died four days later.

Emily Davison is struck by King George’s horse, Anmer, and knocked unconscious

Her funeral, organised by the WSPU, was held in London, with thousands of people lining the streets. Her body was then taken to King’s Cross Station and returned to her family in Northumberland for burial. On 15th June, Emily was buried in Morpeth, a short distance from her mother’s home in Longhorsley, with her mother’s inscription “Welcome home the Northumbrian hunger striker” and “Deeds not words”, the WSPU motto, on her headstone.

The Aftermath

It is still uncertain whether Emily truly intended to kill herself in the name of the suffragette cause that day. In her handbag was found a return train ticket and an invitation to a suffragette meeting that night, which do not suggest that the incident was planned. However Emily’s previous actions might suggest she was prepared to kill herself for the cause.

Emily certainly believed that a sacrificial act would serve to raise the profile of the suffragette cause. However this was not so.

The public viewed her actions as those of a “mentally ill fanatic” and some previous supporters of the suffragette movement were so appalled by the incident, they ceased to be associated with “the cause”. The media concentrated on the wellbeing of the horse and jockey (who seemed to never recover from the guilt he felt) rather than the cause for which Emily died.

The First World War then pulled society together and took the focus away from political activism of this sort. It was not until 1928 with the passing of the Equal Franchise Bill, that women over 21 were finally allowed the vote.

Published: 7th December 2016