In 1216, England was in the midst of a civil war known as the First Barons’ War which was ignited by rebellious landowners known as barons who opposed King John of England and wanted to install a French king in his place.

In the ensuing conflict, King Philippe’s son, Prince Louis would sail to England and launch his invasion whereby he would be proclaimed unofficially “King of England”.

Whilst the French supported by the rebel barons ultimately failed in their quest for power, this was a period of tangible threat to the future of the English monarchy.

The context for the French invasion of the English coastline begins and ends with the disastrous reign of King John who not only lost his overseas French possessions which contributed to the collapse of the Angevin Empire, but also alienated his support at home by demanding an increase in taxation which crucially lost him baronial support.

King John was the youngest son of King Henry II of England and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine. As the fourth son he had not been expected to inherit substantial possession of land and as a consequence was nicknamed John Lackland.

In the coming years, John would mismanage the power bestowed on him by his elder brother, particularly when he was appointed Lord of Ireland.

In the meantime, his eldest brother became King Richard I, also known as Richard the Lionheart for his escapades in the Middle East. As Richard’s time became consumed with the Crusades and matters overseas, John began to plot behind his back.

In time, after hearing news of Richard’s capture in Austria, John’s backers invaded Normandy and John declared himself King of England. Whilst the rebellion proved ultimately unsuccessful when Richard was able to return, John did cement his position as a contender for the throne and when Richard passed away in 1199, he achieved his ultimate dream of becoming King of England.

Now King John I, it was not too long before conflict ensued once more with England’s closest continental neighbour, France.

Whilst John’s forces were not without their victories, ultimately he struggled to retain his continental possessions and in time, his reign bore witness to the collapse of his northern French empire in 1204.

Much of the remainder of his reign would be spent trying to claw back this lost territory by reforming his military and raising taxes.

This however was going to have a disastrous effect on his domestic audience back home and when he returned to England, he was faced with a major rebellion by the powerful barons who did not approve of the impact of his fiscal reforms.

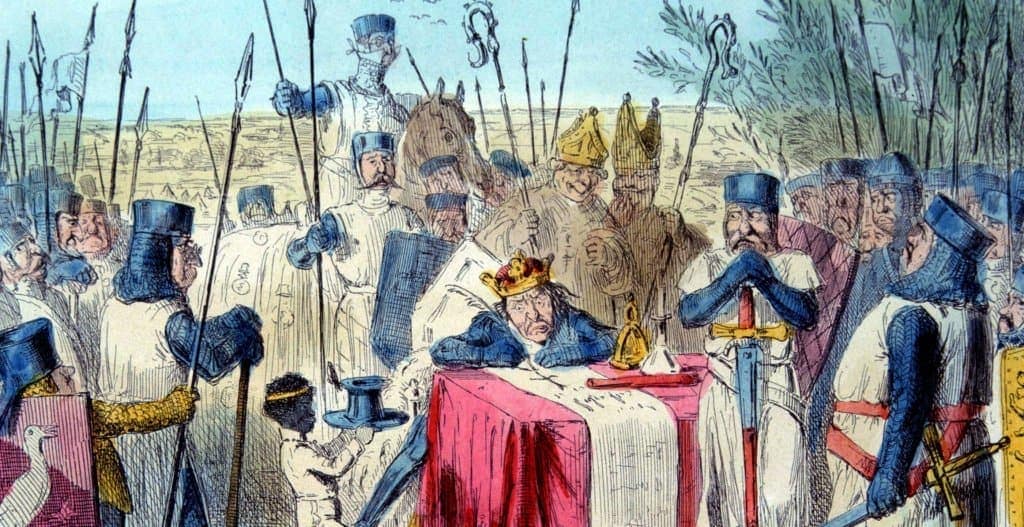

In order to broker a deal between these warring factions, the famous Magna Carta emerged as a charter designed to establish the liberties to be enjoyed by the barons, as well as stipulating the restrictions of the monarch.

Unfortunately the issue of the Magna Carta in 1215 was not enough to cement a lasting consensus on power sharing, particularly when conditions within the agreement were reneged on by all concerned.

Inevitably, such divisiveness spilled into a civil war which was formally known as the First Barons’ War, ignited by the landowning class and led by Robert Fitzwalter against King John.

In order to achieve their goals, the rebel barons turned to France and sought the power of Prince Louis.

Whilst King Philippe of France was keen to remain on the fringes of such a conflict, his son and future king, Prince Louis, accepted the barons offer to install him on the English throne.

With decisions finalised, in 1216 Prince Louis sailed with his military contingent to England, despite the misgivings of his father as well as the Pope.

In May 1216, the French invasion of the English coastline began with Prince Louis and his large army arriving at the Isle of Thanet. Accompanying the prince was a substantial military contingent along with equipment and around 700 ships.

In no time at all, with the support of his English baron allies Louis quickly took control of large parts of England and triumphantly made his way to London with an opulent procession at St Paul’s.

The capital city would now become the headquarters for Prince Louis and sermons were given urging residents to throw their support behind the French prince.

His arrival in London saw him unofficially proclaimed “King of England” by the barons and in no time at all, popular support for the French monarch was increasing steadily as were his military gains.

After capturing Winchester, by the end of the summer Louis and his army had roughly half of the English kingdom under their control.

Even more telling, King Alexander of Scotland payed a visit to him in Dover in order to pay homage to the new King of England.

Whilst significant early gains were made by the French, in October 1216 the dynamic of the conflict greatly changed when King John died of dysentery whilst campaigning in the east of England.

Upon his death, many of the barons who had rebelled against his particularly unpopular reign now turned their support to his nine year old son, the future King Henry III of England.

This resulted in many of Louis’s backers switching allegiances and deserting his campaign in favour of seeing John’s son ascend the throne.

On 28th October 1216, young Henry was crowned and the rebel barons who had castigated and vilified his father, now saw a natural end to their grievances in a new kingship.

With support for Louis now dwindling, the gains he had initially made would prove not to be enough to hold onto power.

Those still backing the French pointed to King John’s failures and also claimed that Louis had a legitimate entitlement to the English throne via his marriage to Blanche of Castile, John’s niece.

In the meantime however, under the recently crowned Henry III and his regency government, a revised Magna Carta was issued in November 1216 in the hope that some of Prince Louis’s backers would be coerced into re-evaluating their loyalties.

This was not however enough to curb the fighting, as the conflict would continue into the following year until a more decisive battle would decide the fate of the next English monarch.

With many of the barons defecting back to the English Crown and willing to fight for Henry, Prince Louis had a big task on his hands.

Such events would reach their climax at Lincoln where a knight called William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke would serve as regent for Henry and gather together almost 500 knights and larger military forces to march on the city.

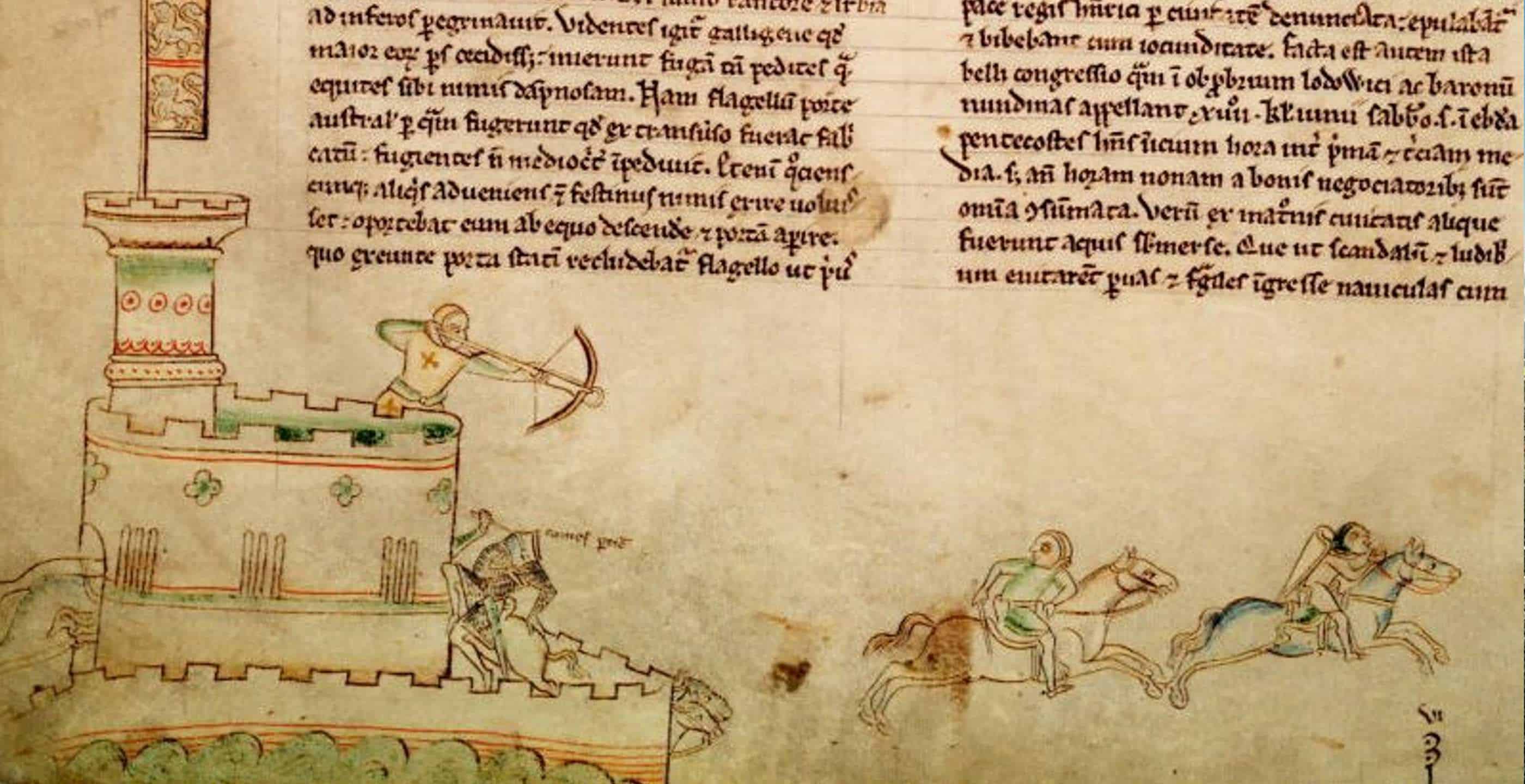

Whilst Louis and his men had already taken the city in May 1217, Lincoln Castle was still being defended by a garrison loyal to King Henry.

Ultimately, the attack launched by Marshal proved successful and the Battle of Lincoln would remain a significant juncture in the First Barons’ War, determining the fate of the two warrying factions.

Marshal and his army did not hold back as they pillaged the city and purged those barons who had made themselves enemies to the English Crown by their support of the French Prince Louis.

In the coming months, the French made a last ditch effort to regain control of the military agenda by sending reinforcements across the English Channel.

As the hastily assembled fleet arranged by Blanche of Castile set sail, it was soon to meet an untimely end as a Plantagenet English fleet under Hubert de Burgh launched its attack and successfully captured the French flagship led by Eustace the Monk (mercenary and pirate) and many of the accompanying vessels.

These maritime events known as the Battle of Sandwich (sometimes referred to as the Battle of Dover) occurred at the end of summer 1217 and ultimately sealed the French Prince’s fate and that of the rebel barons.

Whilst the remaining French fleet turned around and headed back to Calais, Eustace, an infamous pirate, was taken prisoner and subsequently executed.

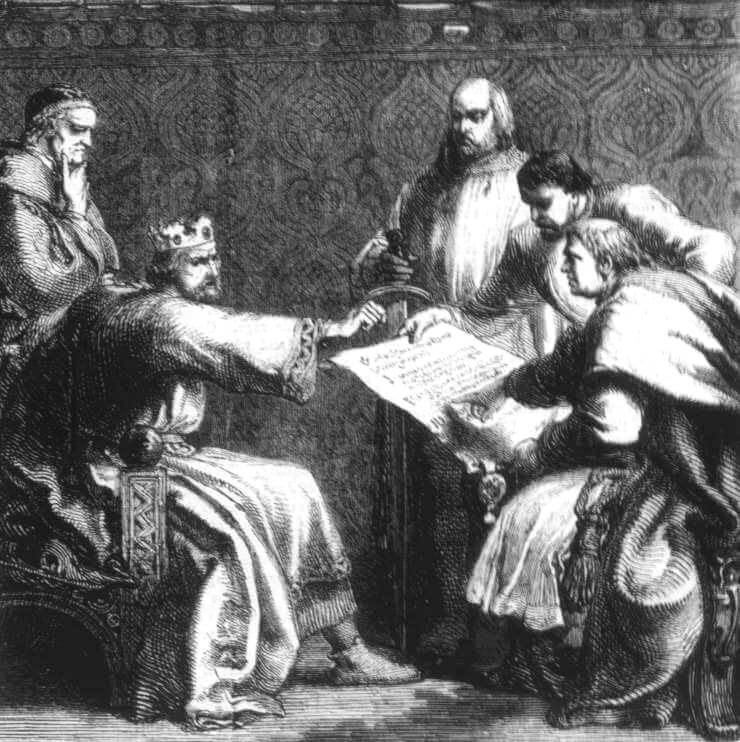

After such a crushing military blow, Prince Louis was forced to concede and agree to make a peace accord known as the Treaty of Lambeth which he signed a few weeks later, formally ending his ambitions to become King of England.

The Treaty of Lambeth (also known as the Treaty of Kingston) signed on 11th September 1217 saw Louis give up his claims to the English throne as well as territory and return to France. The treaty also included the stipulation that the agreement confirmed the Magna Carta, a significant moment in the development of English political democracy.

Such substantial consequences underpin the impact of the French invasion of 1216 in British history. The signing of the treaty brought about an end to the civil war, saw the French prince return to his homeland and bore witness to the reissue of the Magna Carta.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published 16th January 2023