Sea travel in ancient times could be a dangerous business and travelling into unfamiliar territory and the uncertainty of what might be encountered, a perilous affair. The shores of Gaul were once considered as being at the end of the world and almost another world. Accounts of Emperor Claudius’ legions on the eve of his invasion of Britain in 43 A.D., tells of them at first flatly refusing to face a voyage to Britannia, this place outside the world with its dangers of being wrecked or castaway on a hostile shore. Although Julius Caesar in 55 B.C. had shown that an invasion across Oceanus Britannicus from Gaul was feasible, Claudius’ army may still have feared that anyone travelling that far could fall off the edge of the earth.

Following the conquest, Britannia became a Roman province. As a province it developed a number of ports to handle the increase in shipping, including Portus Dubris (Dover), Portus Rutupiae (Richborough), Portus Lemanis ((Lympne) and in Gaul, Gesoriacum. Gesoriacum developed around an expanding port and linked the continent to Britannia. The sea journey across Oceanus Britannicus (the English Channel) from Gesoriacum to the port of Rutupiae in Britannia (Richborough, Kent) was recorded in the Antonine Itinerary as a distance of four-hundred and fifty stadia, 56.25 Roman miles. This was the most direct route to Britannia. It is thought that three hundred and fifty stadia would be closer to the actual distance, however the need to navigate hazards in the channel could account for the the extra one hundred stadia recorded in the Itinerary. Depending on the weather, the journey across the channel to Britannia could take a ship six to eight hours.

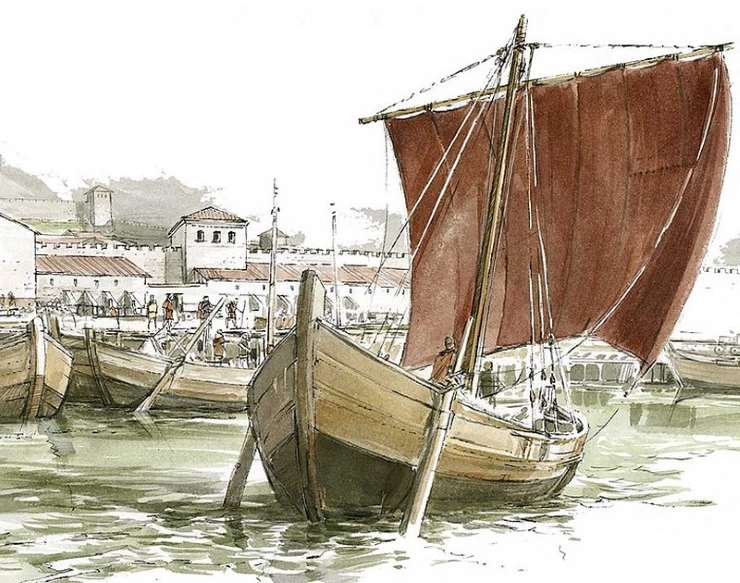

For those travellers who were accustomed to sailing the Mediterranean, the weather conditions they could encounter on Oceanus Britannicus would be considerably more hazardous. Oceanus Britannicus was known for its precarious waters, with massive tides and currents accompanied by variable winds which could make for a difficult crossing. The channel during the winter is far more prone to violent winds than the stormiest region of the Mediterranean. Although the frequency of powerful winds blowing through the channel is greatly reduced during the summer, modern records suggest that ships sailing between Britain and the continent in July still expect to encounter strong or gale force winds on two percent of occasions. In the Mediterranean, tides are hardly perceptible in comparison to tides around the coast of Britain, which can rise and fall anywhere between 1.5 to 14 meters twice daily. Romans made ships for these harsher conditions which would withstand the tidal waters of the north western hemispere. Ships were designed with high bows and sterns to protect against heavy seas and storms. These vessels were also built flat bottomed, enabling them to ride in shallow waters and on ebb tides.

Navigation across the channel was aided by pharos. The lighthouse Tour d’Ordre at Gesoriacum and on the opposite coastline, a pair of pharos, momumental structures at a height of over twenty metres, were situated on the headland flanking either side of the major port of Dubris. The remains of one of these lighthouses survives within Dover Castle. The Romans also maintained a fleet, the Classis Britannica, present in the channel from the 1st century A.D. which provided security for crossing vessels. The fleets purpose was to transport men and supplies and patrol the channel keeping the sea routes free of pirates. The fleet with its headquarters in Gesoriacum, the major Roman naval base for the north of the Empire, also had a permanent base at Dubris (Dover) and Lemannis (Lympne).

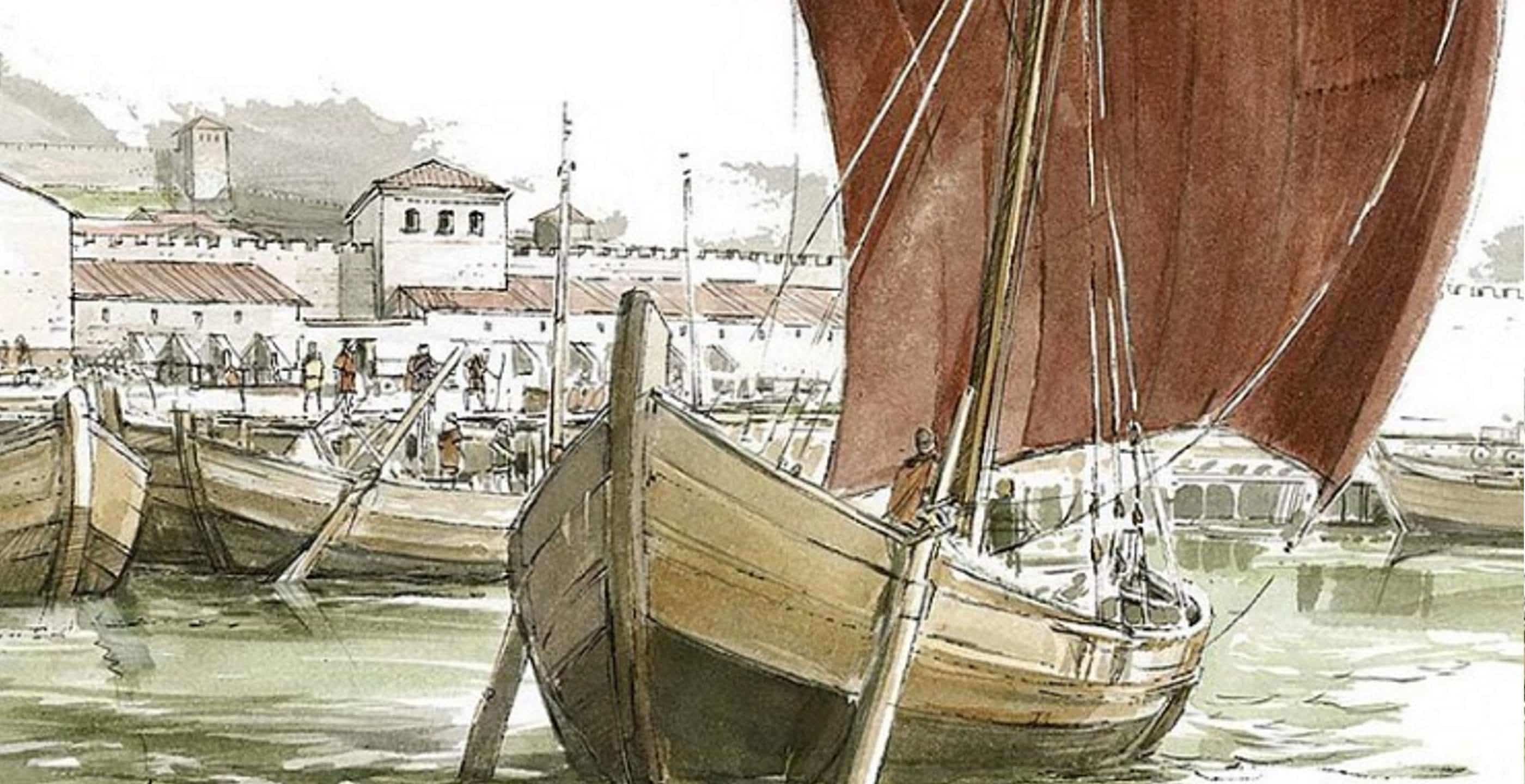

On arrival in Gaul at the port in Gesoriacum, a traveller would find himself in the midst of a hub of activity: merchant ships and naval vessels in the harbour and the busy shipyards carrying out repairs and maintenance. Journey plans for crossing Oceanus required flexibility. There was no routine sailings and to organise his passage the traveller would set about finding the next available ship. He would also need to be aware that not only unsuitable weather conditions prevented sailings, also on ill-omened days; on dates such as the 24 August, 5th October and 8th November, no ship would leave port. Once the next available sailing was found, a deck passage would be booked with the master of the ship, the magister navis.

Ships were merchant vessels not given over to comforts for those passengers on board. There were no cabins, although sometimes small tent-like shelters were used. Before sailing, the ships authorities would always carry out the pre-sailing sacrifice to the gods of a sheep or a bull at the harbour’s temple. Larger ships might have had an altar and a sacrifice could be made on board. If the omens were not right, the sailing would be delayed, positive signs combined with good weather ensured departure. The traveller, anxious for his own personal protection, might also have appealed to Mercury, the god of safe travel. Julius Caesar wrote that Mercury was the most popular god in Gaul and Britannia. One common practice for protection was to wear a brooch depicting a cockerel, herald of each new day, which was associated with the god.

Ancient sea journeys could be uncomfortable and fearful. Once on board, the traveller might settle his nerves and occupy himself by talking with other passengers or perhaps by watching the handling of the vessel; the helmsman guiding the ship, pushing and pulling on the tiller bars or the sailors trimming the lines of the main sail and the deckhands carrying out their duties.

The journey across Oceanus Britannicus with all its possible hazards was nevertheless, a relatively short crossing. On a fine day, there would be a clear and comforting view of Britannia. Approaching the coast of this remote province, the high chalk cliffs of Dover towered, “stupendous masses of natural bulwarks,” was how they were described by one Roman general. For the traveller it must have been a very welcoming sight.

By Laura McCormack, Historian and Researcher.