Have you ever wondered where all the money came from to construct those magnificent medieval cathedrals that stand proudly in the centres of the beautiful and historic cities of England? Or the money to build the myriad of castellated churches that form the focus of a multitude of fine English villages, towns and cities? It was indeed the Wool Trade that funded most of this building, as well as paying for the many medieval wars that England waged during this period. Sheep were indeed the beating heart of the national wealth.

So how was it that England, in medieval times, formed the very epicentre of Europe’s wool trade? Washed with the finest rain in Europe, the lush green fields of England could satisfy even the most voracious appetites of those domesticated ruminants. Just one small issue hampered the English countryside from being the ‘perfect natural sheep farm’: wolves!

Early records from Roman and later Saxon chronicles indicate that wolves appear once to have roamed the countryside in great numbers.

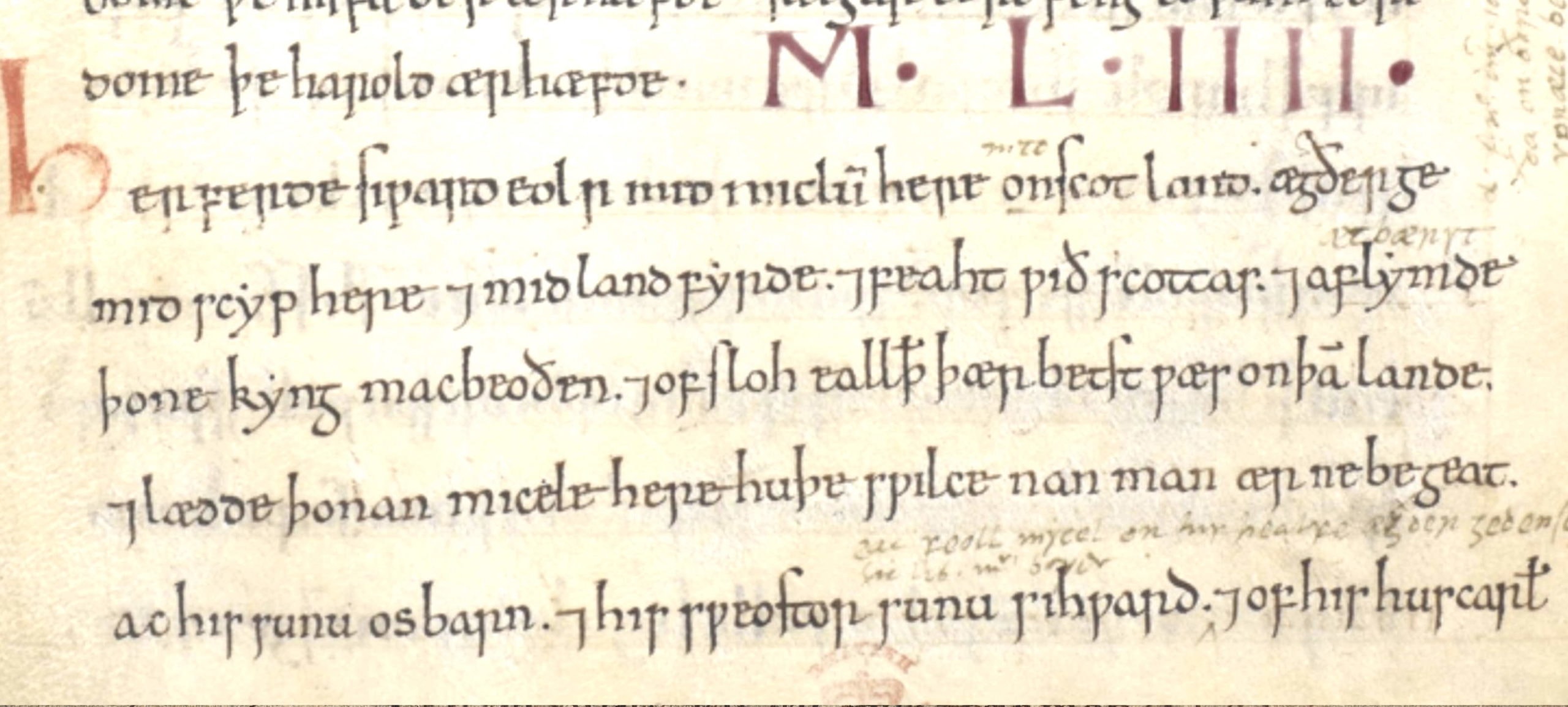

Indeed, one Anglo-Saxon manuscript, written in AD800, records an East Anglian ruler called “Wuffa” and his tribe, known as the “Wuffings” or Wolf People. Wuffa is thought to have ruled around AD575.

The monk Galfrid observed that wolves were so numerous in Northumberland that it was virtually impossible for shepherds to protect their sheep. In AD 950 King Athelstan imposed an annual tribute of 300 wolf skins on Welsh king Hywel Dda, as wolves were causing a particular problem in the English counties that bordered Wales. Indeed, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records January as “Wolf monath”, the first month of the wolf hunting season. The hunting season would continue until 25th March, when during the cubbing season, wolves were at their most vulnerable.

In Norman times, William the Conqueror granted the lordship Riddesdale in Northumberland to Robert de Umfraville, on the condition that he defend the land from both enemies and wolves. By the time of the Magna Carta in 1215, King John was offering a reward of five shillings for each wolf pelt submitted.

King Edward I, who reigned from 1272 to 1307, ordered the total extermination of all wolves in his kingdom and personally employed a Shropshire knight, one Peter Corbet to rid England’s western shires – Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire and Worcestershire – from the grim scourge of the wolf.

Corbet was well known to Edward, having fought alongside him at the Battle of Falkirk where they defeated William Wallace in 1298. He also served in Edward’s Welsh campaigns of 1277, 1282 and 1294-5. Corbet appears to have taken to his new role with certain amount of gusto; along with his men and pack of dogs, he rode through the royal forests of the Welsh Marches culling all that he found. So effective was he that he earned the title ‘the Mighty Hunter’.

Not all wolves were hunted however, many were trapped. One family in particular, the Wolfhunts, who resided in the Forest of High Peak, then a royal hunting reserve, would enter the forest with barrels of pitch. The pitch would be spread over the ground where it was known that the wolves roamed. During dry summer days they would then return to destroy any trapped cubs.

During the latter half of the fourteenth century, Edward III granted land near Kettering in Northamptonshire to Thomas Engaine, on the condition that he find special hunting dogs to rid the shires of Buckingham, Huntingdon, Northampton and Oxford of wolves, foxes and other vermin. The Engaine family crest shows a wolf trapped between a spear and an axe.

It is generally accepted that wolves had all but been irradicated from the English countryside by the reign of Henry VII, sometime around the year 1500. By this time, wolves had been driven to a meager existence living in the wilder forests of Lancashire, the Peak District and Yorkshire Wolds.

But it was really from the end of the thirteenth century that the country’s prosperity flourished when, thanks to the efforts of the Great Wolf Slayers, England could now be regarded as the ‘perfect natural sheep farm’. By this time the great Cistercian houses of Yorkshire – The White Monks at Rievaulx, Fountains Abbey, Kirkstall, Meaux, Sawley, Byland, and Jervaulx – had also established themselves as a great power in the realm, each with flocks totaling several thousand sheep apiece.

By 1290, it is estimated that there were some 5 million sheep in England, producing around 30,000 woolsacks a year. Just a century later, in the reign of Henry V, almost 63% of the Crown’s total income came from the tax on wool – indeed the beating heart of the national wealth.

Still later in the 14th century, King Edward III decreed that his Lord Chancellor should sit on a bale of wool, now known as the ‘Woolsack’ in order to symbolise the great importance of the wool trade to the economy of England.

Today the Lord Speaker in the House of Lords sits on the Woolsack. Covered in red cloth, it resembles a large cushion and was re-stuffed in 1938 with a blend of wool from Britain and other Commonwealth countries.

Published: 17th March 2023