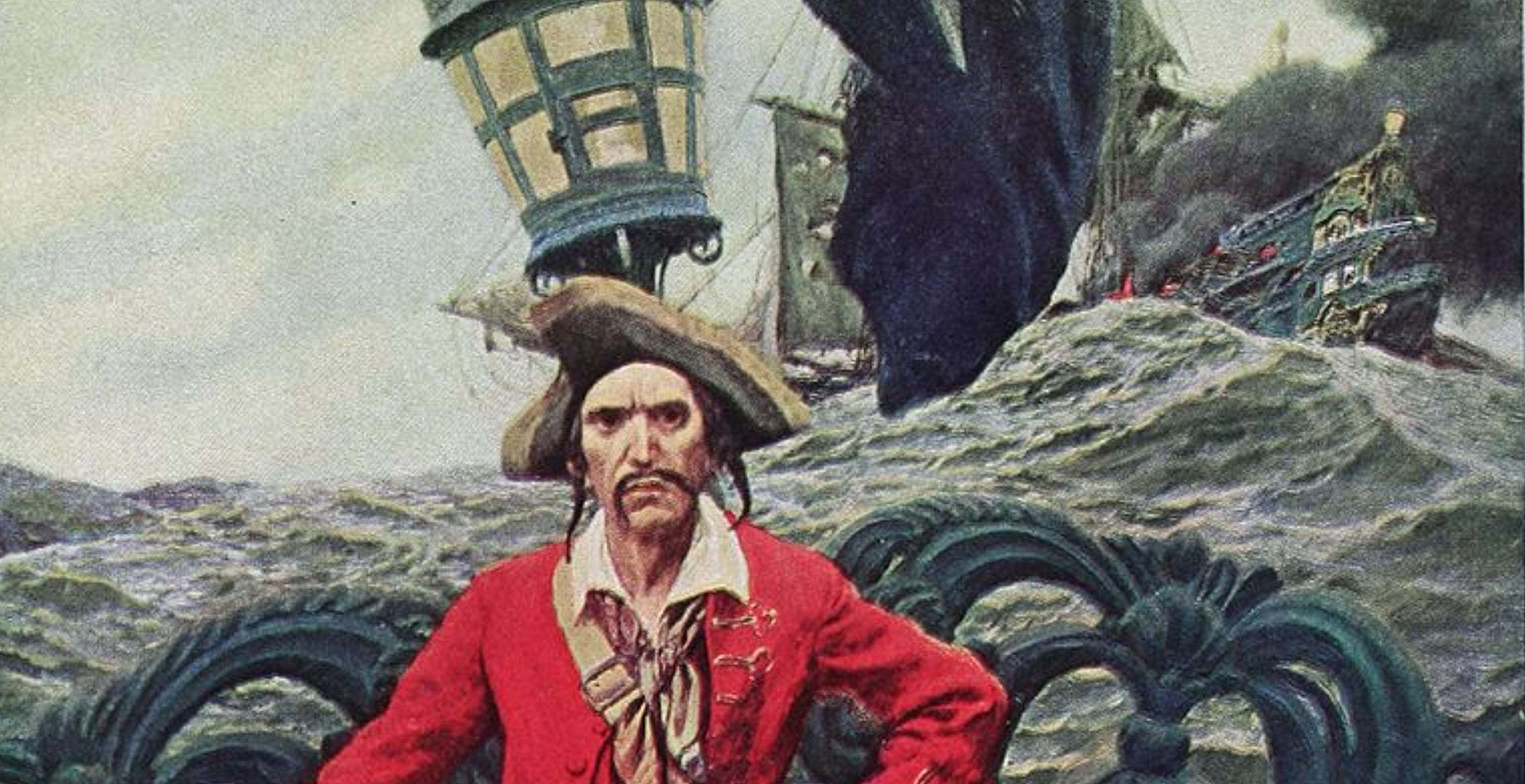

A man known by many aliases, Henry Avery, also known as Henry Every, John Avery and Benjamin Bridgeman, was first and foremost the ‘King of Pirates’, a man who would go on to inspire many other adventurers to follow in his footsteps.

Whilst much of his early life remains shrouded in mystery, he is thought to have been born in the area of Plymouth in Devon, the son of John Avery and his wife Annie.

He began his career by joining the Royal Navy at a time of great international conflict and upheaval, which saw him participate in many battles and naval manoeuvres around the world.

One of the most significant conflicts to take place during his naval career was the Nine Years’ War which broke out in 1688 and involved England fighting alongside the Grand Alliance which included the Dutch Republic, Bavaria, the Palatinate, Saxony and Spain. This international collaboration was designed to quell the growing ambitions of Louis XIV of France.

During this time, Avery was working on board HMS Rupert, a sixty-four gun ship as a midshipman under the command of Sir Francis Wheeler.

In 1689, Avery was granted the opportunity of a promotion to become a master’s mate after HMS Rupert secured a significant victory against the French.

The following year, he joined the ninety-gun HMS Albermarle on the invitation of Captain Wheeler but sadly was involved in the crashing defeat of the English at the Battle of Beachy Head. The loss subsequently caused panic in England, as control of the English Channel temporarily fell into the hands of the French.

For Avery it was significant as his last battle in the navy as only a month later he was discharged from the Royal Navy.

Consequently, he was forced to turn his attentions elsewhere in order to find an income and landed an opportunity to work in the Atlantic slave trade.

He found employment with the royal governor of Bermuda and was given the job of transporting enslaved Africans across the Atlantic to the Americas, primarily operating along the Guinea coastline.

Avery’s ruthless character proved quite suited to such an insidious task, as many fellow slave traders noted Avery’s brutal tactics.

After his stint in the slave trade, Avery turned his attentions to piracy, an adventure that promised thrills and potentially lucrative rewards.

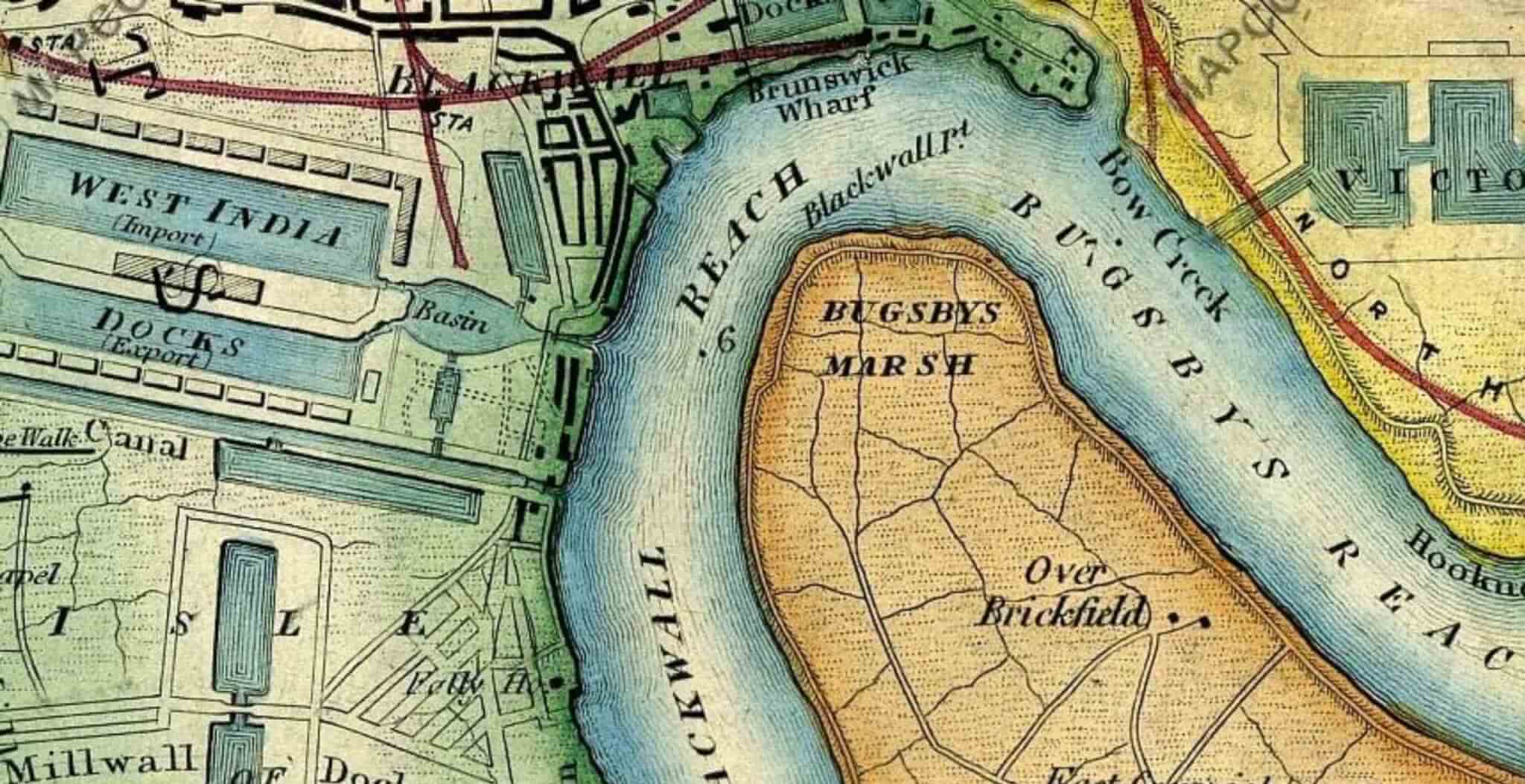

In 1693, in light of a stagnating economic situation, a group of London investors led by a wealthy merchant called Sir James Houblon decided to launch a venture called the Spanish Expedition Shipping. This involved four warships including the Charles II, on board which Avery would serve as first mate. The fleet was under the command of commander Admiral Sir Arturo O’Byrne, an Irish nobleman with a background in the Spanish Navy Marines.

The promise of good pay enticed men like Avery, as the investors of this venture drew up a contract which guaranteed a monthly wage with the first month paid in advance before the expedition began.

The mission involved sailing to the Spanish West Indies using a trading and salvage license obtained by the Spanish, to conduct trade and supply the Spanish with arms against the French, whilst also recovering treasure from wrecked galleons and raiding French possessions in the vicinity.

The voyage however was plagued by problems. Once all four warships eventually set sail, they followed a route which took them to the northern Spanish city of Corunna. The journey which should have only taken a couple of weeks, turned into a five month long venture. Unfortunately for those on board, the official documentation had not arrived in Madrid, forcing further delays and resulting in no income. They were at a complete standstill and all the crew were effectively prisoners in Corunna without any viable options to expedite matters.

Unsurprisingly, the situation soon became untenable and the men were at loggerheads, unable to leave and devoid of income, many feared the worst, that they had been tricked and sold into slavery to the Spanish.

Eventually in May 1694, the fleet made preparations to leave Corunna, however the crew were by now dissatisfied and disillusioned, leading to a threat of a strike. Whilst Houblon refused to meet their demands, Admiral O’Byrne was more receptive, however an argument between O’Byrne and the men eventually precipitated a mutinous plan.

One of the principal figures in such a plan was Avery, who began recruiting other men to join the cause and by 7th May 1694, the stage was set for a showdown.

Along with twenty-five men, Avery boarded the Charles II, surprising the rest of the crew whilst the captain, who was bedridden, was unable to respond. The mutiny was a bloodless one and in very little time others joined from another ship, bolstering the number of mutineers. The ship came under fire from one of the other warships, however Avery and the mutineers disappeared into the night.

Once in a place of safety, Avery allowed the rest of the crew, who had been ambushed, to go ashore, including Captain Gibson. Once the non-conspirators had left the ship, Avery was unanimously elected as the new captain of the Charles II. With a new man at the helm, the ship was subsequently renamed the Fancy and Avery and his new mutinous crew set sail for the Indian Ocean in search of treasure.

On their way to their destination, the Fancy preyed on numerous ships including robbing three English merchantmen from Barbados, taking with them much needed supplies. Some of the robbed crew were even persuaded to join Avery, who by now had amassed almost 100 men.

Sailing along the Guinea coastline, Avery’s cunning was on full display when he tricked a local chieftain and his men into boarding the ship under the guise of trading prospects, before leaving them without their possessions and enslaved.

Whilst the ship continued to hug the coastline of Africa, the crew briefly stopped in Benin to make some important changes and improvements to the ship, reducing its upper decks to allow the Fancy to increase its speed, making it one of the fastest vessels.

With nothing to hinder its speed, the Fancy continued to plunder as it travelled down the coast of Africa, capturing Danish privateers and stealing the Danish ships’ ivory and gold. A handful of Danish defectors also joined, adding to the swelling number of Avery’s crew.

Finally, by the beginning of 1695, the Fancy had rounded the Cape of Good Hope, taking the opportunity to rest and restock supplies on the island of Johanna in the Comoros Islands. During their stop off, Avery and his crew captured a French pirate ship, which they subsequently looted and recruited from, adding another forty men under Avery’s command.

With his numbers suitably bolstered and now well-rested and with plenty of provisions, Avery could execute his biggest plunder yet, an ambitious plan which would earn him great notoriety.

Under Avery’s leadership, the Fancy set sail to the mouth of the Red Sea, where they would lie in wait for the Indian Mughal government’s Mocha fleet which was returning from Mecca. This fleet was unrivalled in its wealth and if the pirates were successful, the treasures on board would make the raid the most successful in the history of piracy.

In August 1695, the Fancy and its crew reached the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb and joined forces with five other pirate ships. Avery was subsequently elected admiral of this newly formed pirate flotilla and was in command of almost 500 men.

With their eyes set firmly on the prize, the ships waited for the convoy of twenty-five Grand Mughal ships to come into view.

The Indian ships proved to be a formidable sight, particularly the grandiose Ganj-i-sawai which was 1600 tonnes and had a crew of more than 1000 as well as enormous gun power. With around eighty cannons to boast of, it was by no means an easy target.

On 7th September 1695, Avery commanded his men to board the vessels, leading to a ferocious battle involving hand-to-hand combat and all manner of brutality until finally the pirates over-powered their opponents. The captives were subsequently subjected to extreme violence, including the rape of many of the women on board, as well as torture to extract information.

Once the ships had been stripped bare of all their wealth, jewels and treasures, the survivors of the attack were left to board their empty ships and set sail back to India.

Meanwhile, Avery and his fellow pirates could enjoy the plentiful and unimaginable wealth of treasures they had plundered, with precious metals and jewels amounting to £600,000 (roughly £115 million today).

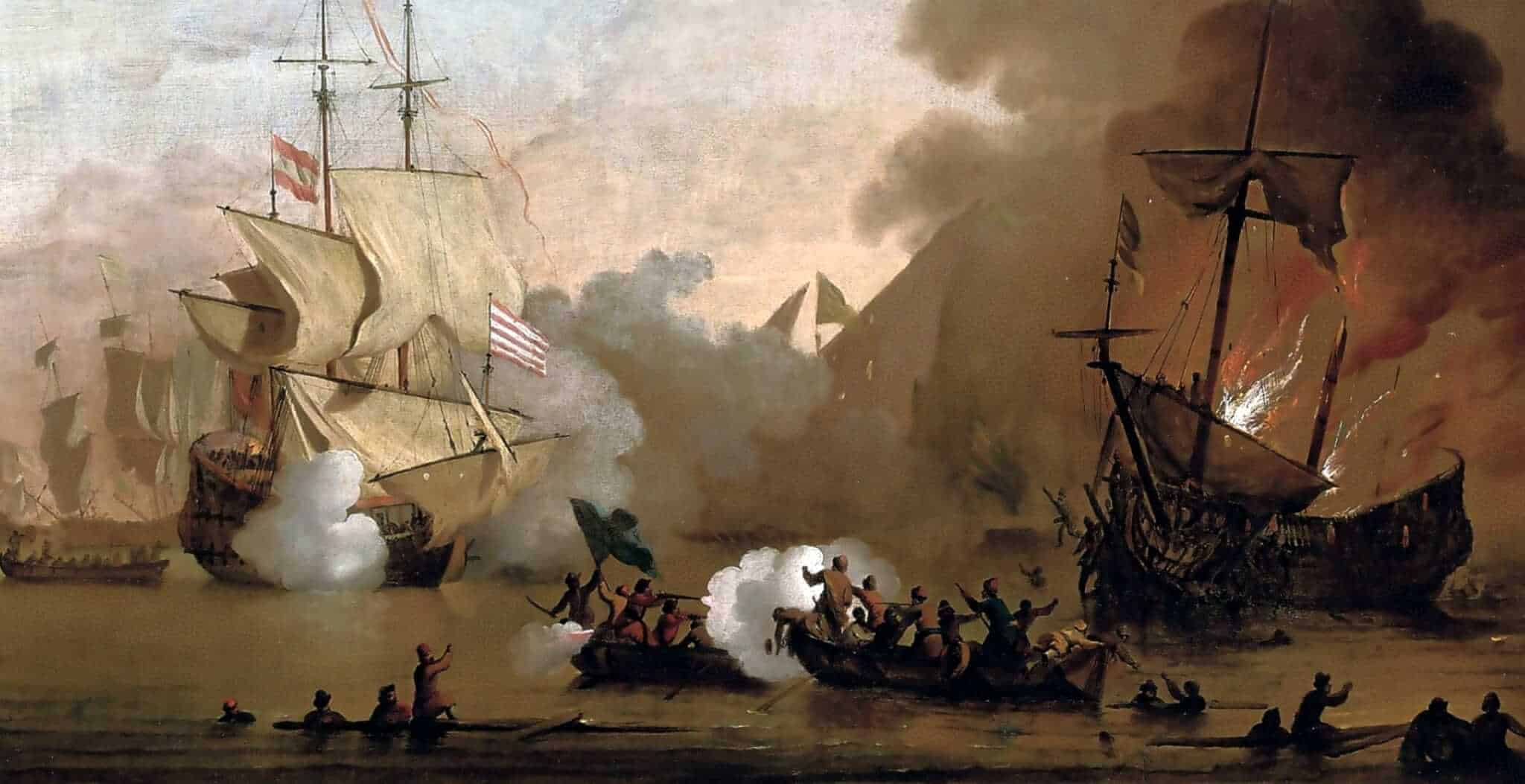

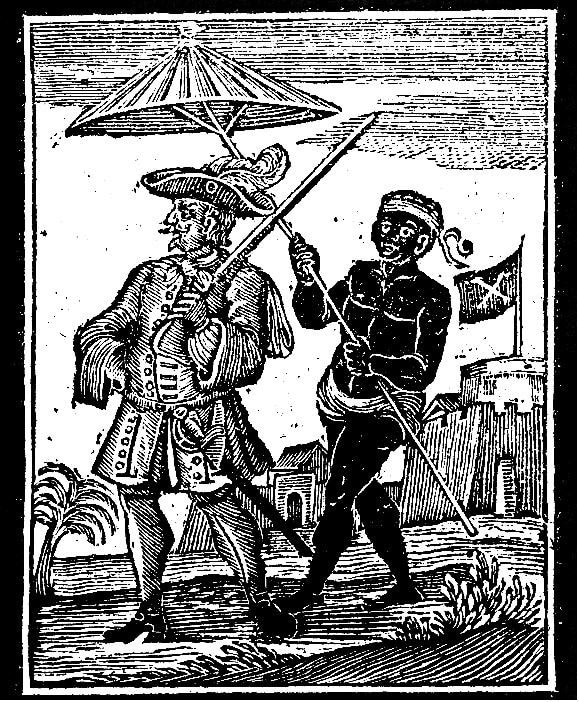

An 18th-century depiction of Henry Every with the Fancy, shown capturing the Grand Mughal Fleet

An 18th-century depiction of Henry Every with the Fancy, shown capturing the Grand Mughal Fleet

The ramifications of having stolen such an impressive loot fell on the English, who now had to face the wrath of Mughal relations. As a result, the Privy Council and the East India Company set a bounty of £1,000 for Avery’s capture, launching one of the most significant, and potentially the first global, manhunt of its time.

The East India Company would suffer great damage both in terms of its international relations and economically as imports dropped sharply as a result of Avery’s avarice. The EIC’s factories in India soon found themselves under attack and the EIC was forced to negotiate and offer reparations as a result.

Avery meanwhile set sail for the Bahamas and the international manhunt began.

The pirates soon scattered themselves across the globe, with some settling in America, whilst others returned home to England where they were eventually found, imprisoned, banished or hanged for their crimes.

Avery however never faced such a fate, his escape proving to elude all those who went in search of him. With no more records as to his whereabouts, the mystery of Avery continues to this day.

In only two years of piracy, Henry Avery had accomplished the unthinkable, achieving one of the best known acts of piracy and making off with riches few could comprehend.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 23rd April 2025.

—