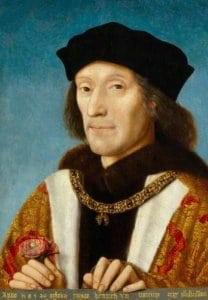

When the public are asked about the Tudors they can always be relied upon to talk about Henry VIII, Elizabeth and the great events of those times; the Armada perhaps, or the multitude of wives. It is however a rarity to find anyone who will mention the founder of the dynasty, Henry VII. It is my belief that Henry Tudor is every bit as exciting and arguably more important than any of his dynasty who followed.

Henry Tudor ascended the throne in dramatic circumstances, taking it by force and through the death of the incumbent monarch, Richard III, on the battlefield. As a boy of fourteen he had fled England to the relative safety of Burgundy, fearing that his position as the strongest Lancastrian claimant to the English throne made it too dangerous for him to remain. During his exile the turbulence of the Wars of the Roses continued, but support still existed for a Lancastrian to take the throne from the Yorkist Edward IV and Richard III.

Hoping to garner this support, in the summer of 1485 Henry left Burgundy with his troop ships bound for the British Isles. He headed for Wales, his homeland and a stronghold of support for him and his forces. He and his army landed at Mill Bay on the Pembrokeshire coast on 7th August and proceeded to march inland, amassing support as they travelled further towards London.

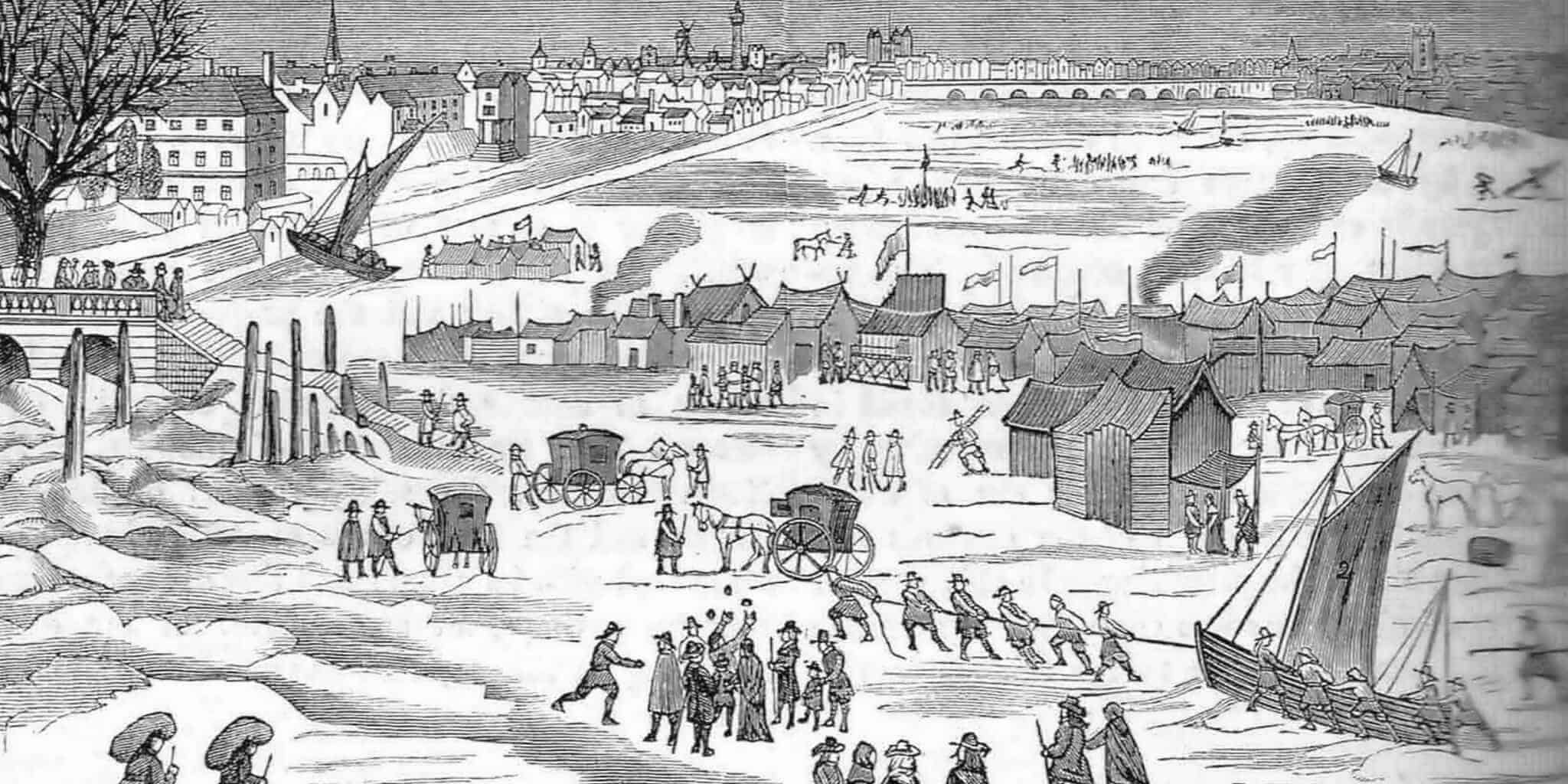

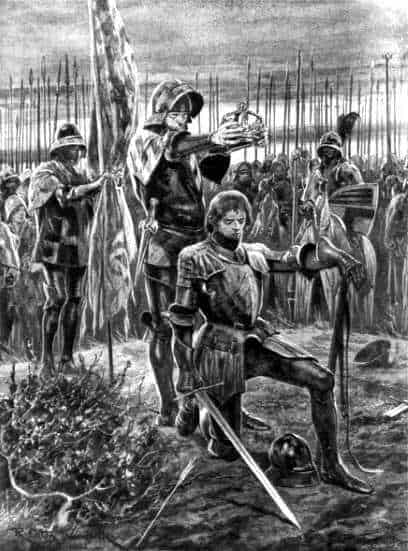

On 22nd August 1485 the two sides met at Bosworth, a small market town in Leicestershire, and a decisive victory was had by Henry. He was crowned on the battlefield as the new monarch, Henry VII. Following the battle Henry marched for London, during which time Vergil describes the whole progress, stating that Henry proceeded ‘like a triumphing general’ and that:

‘Far and wide the people hastened to assemble by the roadside, saluting him as King and filling the length of his journey with laden tables and overflowing goblets, so that the weary victors might refresh themselves.’

Henry would reign for 24 years and in that time, much changed in the political landscape of England. While there was never a period of security for Henry, there could be said to be some measure of stability compared to the period immediately before. He saw off pretenders and threats from foreign powers through careful political manoeuvring and decisive military action, winning the last battle of the Wars of the Roses, the Battle of Stoke, in 1487.

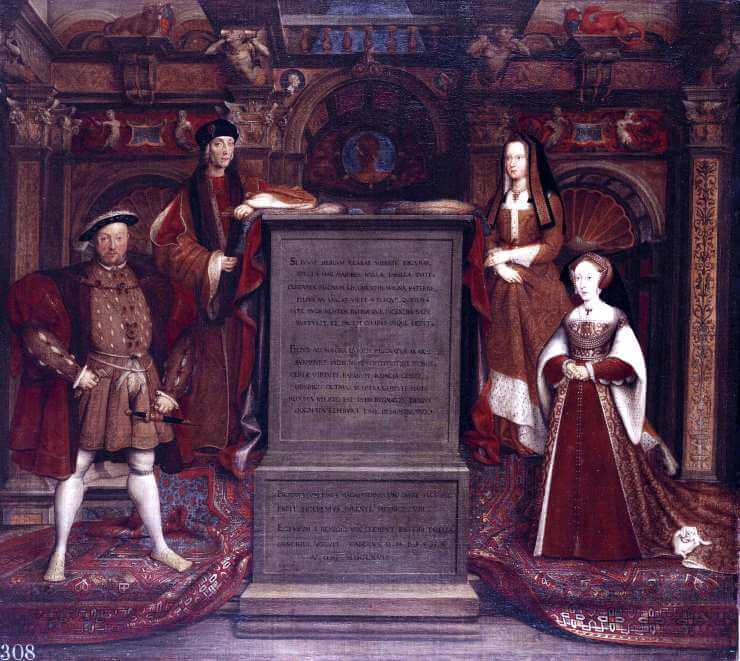

Henry had gained the throne by force but was determined to be able to pass the crown to a legitimate and incontrovertible heir through inheritance. In this aim he was successful, as upon his death in 1509 his son and heir, Henry VIII, ascended the throne. However, the facts surrounding the Battle of Bosworth and the swiftness and apparent ease with which Henry was able to take on the role of King of England do not however give a full picture of the instability present in the realm immediately before and during his reign, nor the work undertaken by Henry and his government in order to achieve this ‘smooth’ succession.

Henry’s claim to the throne was ‘embarrassingly slender’ and suffered from a fundamental weakness of position. Ridley describes it as ‘so unsatisfactory that he and his supporters never clearly stated what it was’. His claim came through both sides of his family: his father was a descendant of Owen Tudor and Queen Catherine, the widow of Henry V, and while his grandfather had been of noble birth, the claim on this side was not strong at all. On his mother’s side things were even more complicated, as Margaret Beaufort was the great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford, and while their offspring had been legitimised by Parliament, they had been barred from succeeding to the crown and therefore this was problematic. When he was declared King however these issues appear to have been ignored to some extent, citing he was the rightful king and his victory had shown him to be judged so by God.

As Loades describes, ‘Richard’s death made the battle of Bosworth decisive’; his death childless left his heir apparent as his nephew, the Earl of Lincoln whose claim was little stronger than Henry’s. In order for his throne to become a secure one, Gunn describes how Henry knew ‘Good governance was required: effective justice, fiscal prudence, national defence, fitting royal magnificence and the promotion of the common weal’.

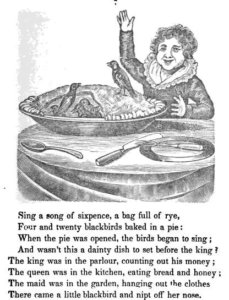

That ‘fiscal prudence’ is probably what Henry is best known for, inspiring the children’s rhyme ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’. He was famous (or should that be infamous) for his avarice which was commented upon by contemporaries: ‘But in his later days, all these virtues were obscured by avarice, from which he suffered.’

Henry is also known for his sombre nature and his political acumen; until fairly recently this reputation has led him to be viewed with some notes of disdain. New scholarship is working to change the King’s reputation from boring to that of an exciting and crucial turning point in British history. While there will never be agreement about the level of this importance, such is the way with history and its arguments, this is what makes it all the more interesting and raises the profile of this oft forgotten but truly pivotal monarch and individual.

Biography: Aimee Fleming is a historian and writer specialising in Early-Modern British history. Current projects include work on topics varying from royalty and writing, to parenthood and pets. She also helps design history-based educational materials for schools. Her blog ‘An Early Modern View’, can be found at historyaimee.wordpress.com.