Nine years after the truce between France and England was cemented by the Treaty of Brétigny, hostilities broke out when the new French King on the throne, Charles V declared war.

This second phase of the conflict became known as the Caroline War, named after Charles V who had resumed the battle with Edward III’s son, Prince Edward, heir to the English throne.

The pretext for this new encounter between the warring kingdoms came from the summons sent by Charles V demanding Edward’s presence in Paris.

Edward’s refusal to comply with the French demands led Charles to turn to war as the only means to resolve the dispute.

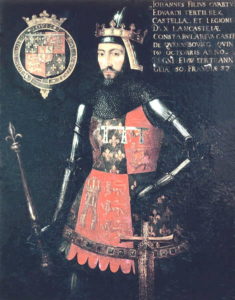

The context for this summons came from the involvement of Prince Edward in the Castilian succession war of 1366.

Edward’s support of King Peter, also known as Pedro the Cruel, led to a severe dent in his finances. Therefore when he returned with his army to Aquitaine, Edward had to find a way to pay off the debts he had accrued during the Castilian campaign.

Edward started to recoup his losses by using a tax rise called the “hearth tax” in Aquitaine in order to shore up his finances.

Unsurprisingly, the residents were far from happy with this arrangement and the Lord of Albret, who had accompanied Edward during the war, deemed the tax illegitimate. He was not alone in his sentiments and thus a small coalition of lords and city officials banded together and appealed to King Charles V to support them in their refusal of the tax.

This resulted in a summons being sent to Edward in May 1369, demanding that he should be seen in Paris where Charles would hold court to hear the case.

With Edward outraged by this suggestion, no amount of discussion could see this summons reach an amicable solution.

With no agreement possible, Charles declared war and the two kingdoms entered into a second phase of fighting known as the “Caroline War”, a chapter of conflict which would last another twenty years before resolution could be found.

In the context of renewed hostilities, Charles V commanded a more favourable position than his English competitors as England at this time suffered from a lack of leadership, with King Edward III now too old and his son, the Black Prince, suffering from ill health.

To make matters worse, England had also lost one of its most celebrated military leaders and strategists, Sir John Chandos in a skirmish on New Years’ Day 1370. His influence and military expertise had proved invaluable as the English knight was believed to have been a fundamental contributor to the success at Crécy and Poitiers. His death dealt a severe blow to the English whilst the French were motivated by their desire to reverse the unfavourable elements of the Treaty of Brétigny.

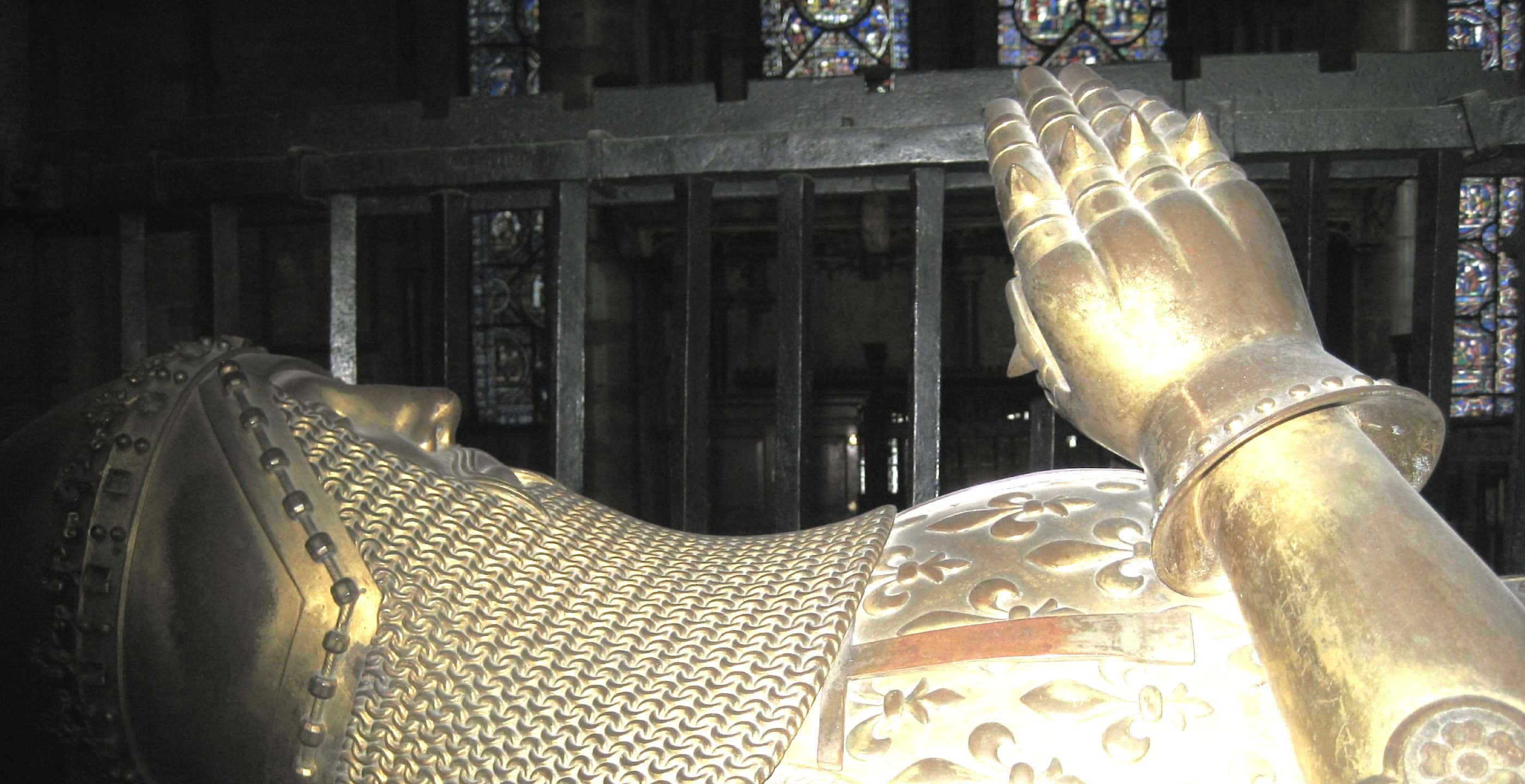

One of the first military encounters in the second phase of the conflict came in the town of Limoges which had fallen into French hands in August 1370.

Siege of Limoges

Siege of Limoges

Under the leadership of Edward, the Black Prince, on 9th September he and his army laid siege to the town, managing to take it by force, leading to the slaughter of thousands of residents. The siege left much destruction and bloodshed in its wake, leaving a permanent impact on the industry for which Limoges was most well-known: enamelling.

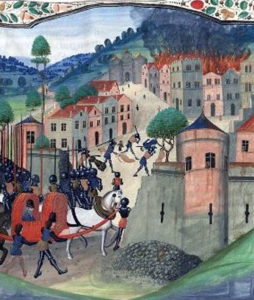

The first major naval engagement would come two years later in 1372 at La Rochelle. Up until now, the English had been able to maintain command of the sea but unfortunately for King Edward, this was all about to change when an English fleet heading towards Aquitaine with supplies was destroyed by a fleet of Franco-Castilian ships.

The Castilian ships had forced an English surrender, with the English losing around twenty ships against the Castilians who used the tactic of spraying oil on the deck of the ships before firing flaming arrows onto their targets in order to ignite the English fleet.

The joint Castilian and French victory had the impact of undermining the English command of the sea as well as affecting their supplies.

Sadly, England would not be able to recoup their losses as the battle at La Rochelle would mark the beginning of many defeats for the English.

The French would prove successful in a series of campaigns under their military leader, Bertrand du Guesclin. He had excellent credentials, having previously fought in the Breton War of Succession as well as the most recent conflict in Castile. By 1370, Charles V had recalled Du Guesclin from Spain and made him the Constable of France, a role which bestowed the great responsibility of leading France to victory.

The success of Du Guesclin was his adoption of the Fabian strategy, whereby pitched battles were avoided in favour of ebbing away at England through more indirect action.

In response, the English used a tactic of medieval warfare called chevauchées, which involved military expeditions of burning and pillaging territory rather than engaging in sieges. The desired effect would be to impact the efficiency of the land and thus devastate the enemy’s economy as well as political stability.

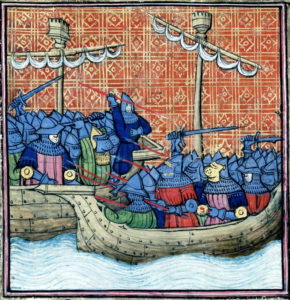

In August 1373, it was John of Gaunt who would lead the Great Chevauchée.

John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt

The English army would launch their expedition in Calais, which marked the beginning of a long and arduous journey which took them five months and resulted in the loss of many lives. The army under John of Gaunt would travel nearly a thousand miles, managing to reach the Loire River, by which point they were lacking in provisions, were suffering from fatigue and had encountered many hostilities along the way.

As the remaining troops made their way across the Loire River, the Duke of Burgundy looked on at this now battle-weary and exhausted troop of men.

By Christmas 1373, John of Gaunt’s men, those who had survived, arrived in Bordeaux, half-starved, with many casualties and even a loss of armoury since it had been too much for them to carry. The Great Chevauchée had proved to be a failure leading to disappointment back home in England.

Meanwhile, Du Guesclin continued to employ his strategy with much success. He achieved a number of victories, including at the Battle of Pontvallain where he drove out any remaining English fighters before going on to Poitou and Saintonge, forcing Prince Edward to leave France.

In 1373, Du Guesclin defeated the English again at the Battle of Chizé as the French laid siege to the town. This would prove to be an important win for the French as it marked the last battle in the bid of recovering Poitou which had, in the Treaty of Brétigny, been assigned to the English. Such a victory by the French looked set to reverse the treaty and in turn diminish English influence in the region.

To make matters worse for the English, Prince Edward’s health continued to deteriorate whilst another crucial military leader, Jean III de Grailly who fought for the English, was captured by Charles V and died in captivity.

In 1376, Prince Edward succumbed to dysentery and died, leaving many of his loyal followers in shock.

Not long afterwards, his father, King Edward III also passed away, leaving a young ten-year-old Richard II on the English throne.

Meanwhile, over in France, a change of leadership would occur when Charles V passed away in 1380, leaving his son to inherit the throne as King Charles VI of France.

The new French king, only eleven at the time, would in time become known as Charles the Mad as he suffered from psychotic outbursts which plagued him throughout his life. This in turn would lead to a power struggle between those wishing to seize control from the unstable king.

With hostilities still in progress, the death of both kings, Edward III in England and King Charles V in France, marked the beginning of a new era for the monarchy and for the war.

With Richard II and Charles VI both being extremely young, until they came of age their interests would be represented by others.

Under this arrangement, there was political will to find a solution, however the first attempts proved unsuccessful when in 1375, the Treaty of Bruges failed to secure peace.

With Philip II, Duke of Burgundy representing France and John of Gaunt heading up English interests, the treaty had been negotiated by Pope Gregory XI.

Sadly, such peace talks did not come to fruition as the sovereignty of Aquitaine proved an insurmountable obstacle.

By 1377, hostilities looked set to continue and it would take another decade before a truce would finally bring an end to the conflict.

Charles VI of France and Richard II of England sign the Truce of Leulinghem

Charles VI of France and Richard II of England sign the Truce of Leulinghem

On 18th July 1389, Charles VI made peace with Richard II, cemented by the Truce of Leulinghem which agreed a twenty-seven year armistice between the two kingdoms.

With much of the agreement benefiting the French, both still had much to lose, with England on the verge of financial ruin and France suffering from the dilemma of Charles VI’s mental fragility. The incentive to abide by the terms existed for both parties and despite some sustained disagreements over the status of Aquitaine, the ending of war served both their interests.

The Truce of 1389 would instigate a period of peace for the next thirteen years, an armistice which would be cut short in 1402 by resumed hostilities over the lingering issue of Aquitaine.

As England and France entered the final phase of the war only one would prove victorious….

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 24th October 2021