It is likely that Scotland will soon be voting on whether it should become an independent country. A ‘yes’ vote would see Scotland not only withdraw from the UK, but also re-orientate its political and economic relationships from western Europe and the Commonwealth to northern and eastern Europe and particularly, to the Scandinavian countries of Norway and Denmark.

This would not be the first time that Scotland has enjoyed close ties with Scandinavia.

A millennium ago in 1014, a five-hundred year old Anglo-Saxon monarchy was fighting for its survival against the Viking invaders. Whether they liked it or not, England, Wales and Scotland were on the road to assimilation into the North Sea Empire of Cnut the Great, forming a political union with Norway, Denmark and parts of Sweden.

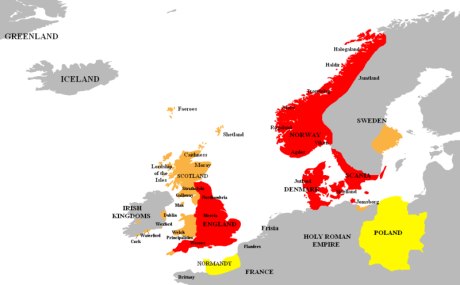

The North Sea Empire (1016-1035): countries where Cnut was king in red;

vassal states in orange; other allied states in yellow

How did this happen? The mid-to-late 900s AD witnessed an Anglo-Saxon golden age of peace and prosperity. Alfred had beaten-off a first Viking attempt to conquer Britain in the late 800s, and his grandson Aethelstan had crushed an attempted reassertion of power by northern Britain at the Battle of Brunanburgh in 937.

But then it all turned sour. Aethelred II came to the throne in 978. Aethelred’s succession was born out of treachery; it’s probable either he or his mother murdered his reigning half-brother, Edward, at Corfe Castle in Dorset, martyring Edward in doing so and prompting the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to lament, ‘…nor among the English was any worse deed done than this since they first sought the land of Britain‘.

In 980 AD, a new Viking campaign against Britain began. The invaders might still have been repelled had the Anglo-Saxons had a decisive and inspirational leader. However Aethelred was neither.

Aethelred’s response to the Viking threat was to hide behind the walls of London and delegate his country’s defence to incompetents or traitors in a series of well-intentioned but appallingly executed operations. In 992, Aethelred assembled his navy at London and placed it in the hands of, among others, Ealdorman Aelfric. The intention was to confront and trap the Vikings at sea before they reached land. Unfortunately, the Ealdorman was not the most astute of choices. The night before the two fleets were due to engage, he leaked the English plan to the Vikings who had time to make good their escape with the loss of just one ship. Needless to say, the Ealdorman also made good his own escape.

Aethelred vented his rage on the Ealdorman’s son, Aelfgar, having him blinded. However not long afterwards the Ealdorman was back in Aethelred’s confidence, only to betray the king again in 1003 when he was entrusted to lead a great English army against Sweyn Forkbeard near Wilton, Salisbury. This time the Ealdorman ‘…feigned sickness, and began wretching to vomit, and said that he was taken ill…‘ The mighty English army crumbled and Sweyn ravaged the borough before slipping back to sea.

By this time, though, Aethelred had already made his greatest mistake. In 1002 he had ordered the execution of all the Danishmen in England in the St Brice’s Day massacre, ‘…all the Danes who had sprung up in this island, sprouting like cockle amongst the wheat, were to be destroyed by a most just extermination…‘. To make matters even worse, Sweyn’s sister and her husband were amongst those massacred. Now what had been a series of disparate Viking raids developed into an all-out campaign for the conquest of Britain.

Aethelred resorted to appeasement by paying huge tributes, or Danegeld, hoping the Vikings would just go away. Not so: in 1003, Sweyn invaded England, and in 1013, Aethelred fled to Normandy and the protection of his father-in-law, Duke Richard of Normandy. Sweyn became King of England as well as Norway. The Vikings had won.

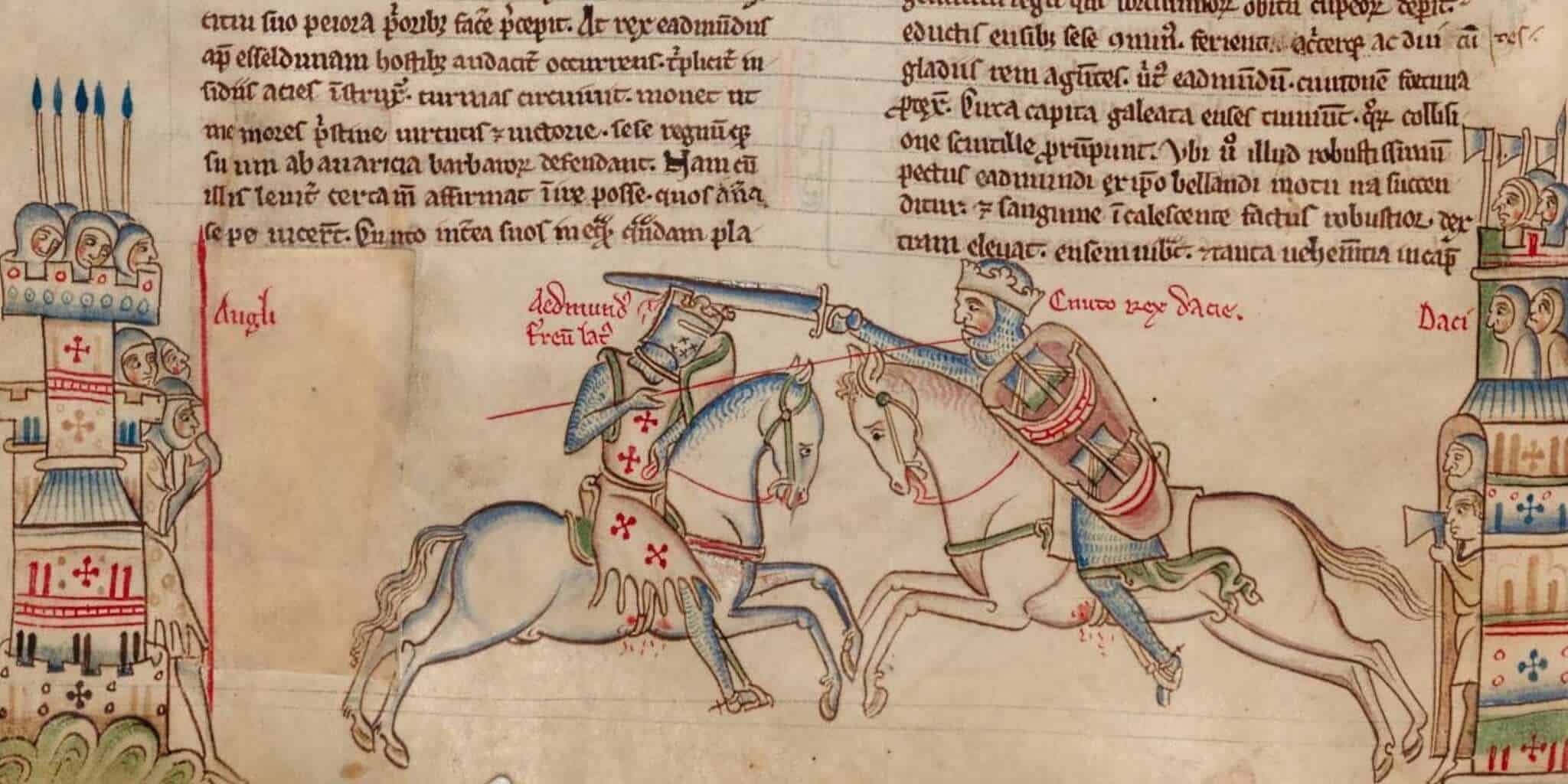

Then Sweyn died in February 1014. At the invitation of the English, Aethelred returned to the throne; it seems a bad king was better than no king. But in April 1016, Eathelred died too leaving his son, Edmund Ironside – a much more able leader and of the same mettle as Alfred and Aethelstan – to take the fight to Sweyn’s son, Cnut. The pair slugged it out on the battlefields of England, fighting each other to a standstill at Ashingdon. But Edmund’s untimely death at the age of just 27 presented Cnut with the throne of England. The Vikings had prevailed once more and Cnut would rule Norway, Denmark, parts of Sweden, and England, with Wales and Scotland as vassal states – all a part of the North Sea Empire which lasted until Cnut’s death in 1035.

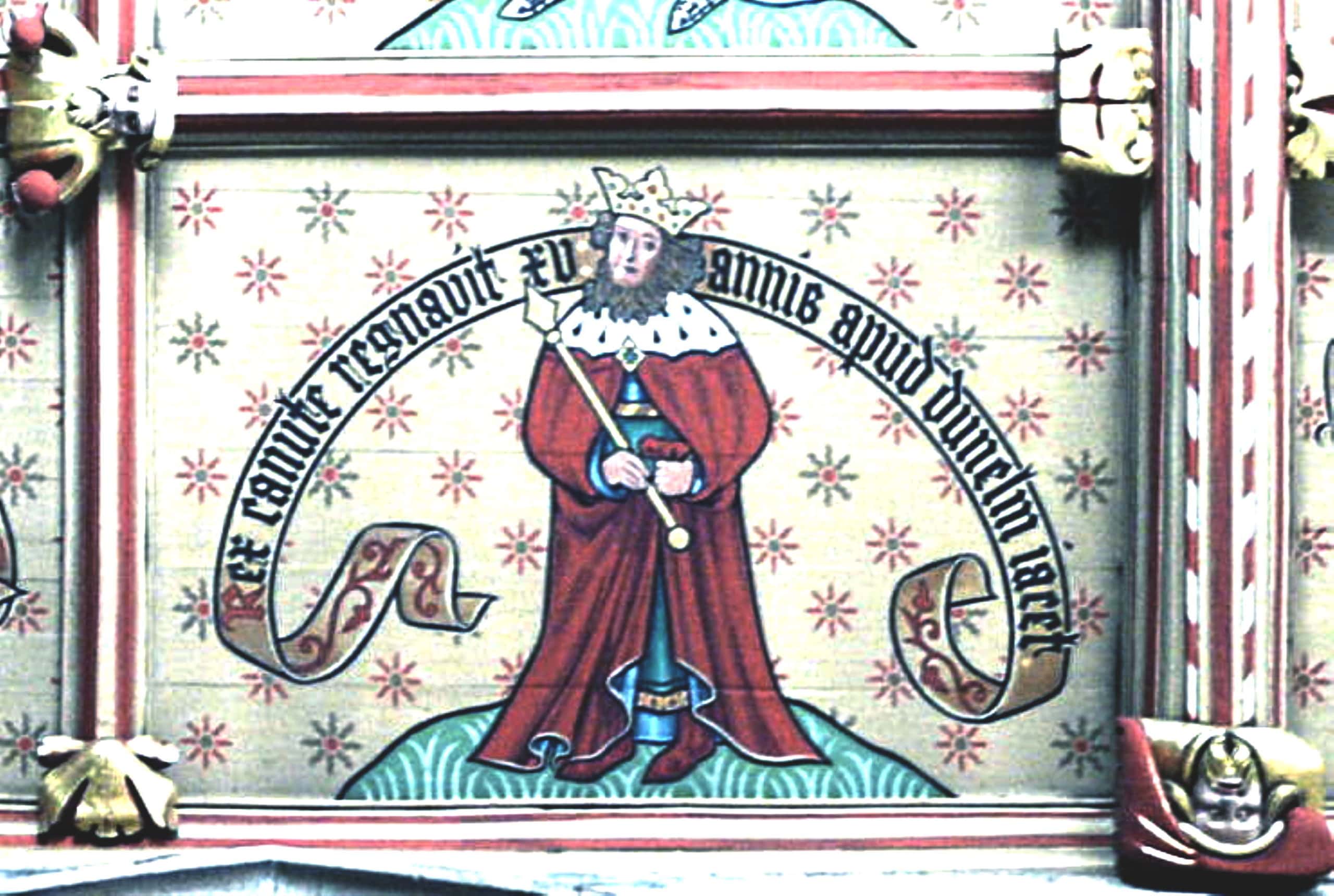

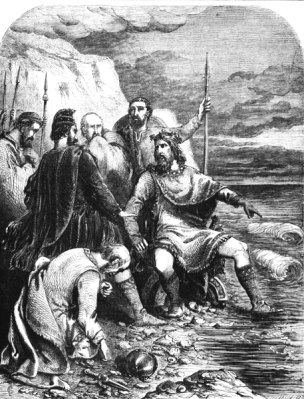

Cnut the Great, king of England from 1016 to 1035, commanding the tide to turn and, by implication, showing his power over the North Sea. However, the demonstration was more intended to show Cnut’s piety – that the power of kings is nothing compared to the power of God.

There is a very old history, then, of Nordic-British integration. Should a 21st century Scotland reach out to Scandinavia, this would evoke strong echoes of the past and, who knows, were Scotland to join the Nordic Council, a lonely England might also be knocking on the door in the event a Tory referendum were to remove it from the EU in a future parliament.