In 1216, at just nine years of age, young Henry became King Henry III of England. His reign saw turbulent and dramatic changes take place with baron-led rebellions and the confirmation of the Magna Carta.

Henry was born in October 1207 in Winchester Castle, the son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême. Whilst little is known of his childhood, in October 1216 his father King John passed away, right in the midst of the First Barons’ War. Young Henry was left to inherit his mantle and all the chaos that came with it.

Henry had inherited not only the Kingdom of England but also the wider network of the Angevin Empire including Scotland, Wales, Poitou and Gascony. This domain had been secured by his grandfather, Henry II, whom he was named after, and later consolidated by Richard I and John.

Sadly, the lands had shrunk somewhat under King John, who ceded control of Normandy, Brittany, Maine and Anjou to Philip II of France.

The collapsing Angevin Empire and King John’s refusal to abide by the 1215 Magna Carta precipitated civil unrest; with the future Louis VIII supporting the rebels, conflict was inevitable.

Young King Henry had inherited the First Barons’ War, with all its chaos and conflict spilling over from his father’s reign.

As he was not yet of age, John had arranged for a council made up of thirteen executors who would assist Henry. He was placed in the care of one of the most well-known knights in England, William Marshal, who knighted Henry, whilst Cardinal Guala Bicchieri oversaw his coronation on 28th October 1216 at Gloucester Cathedral. His second coronation took place on 17th May 1220, at Westminster Abbey.

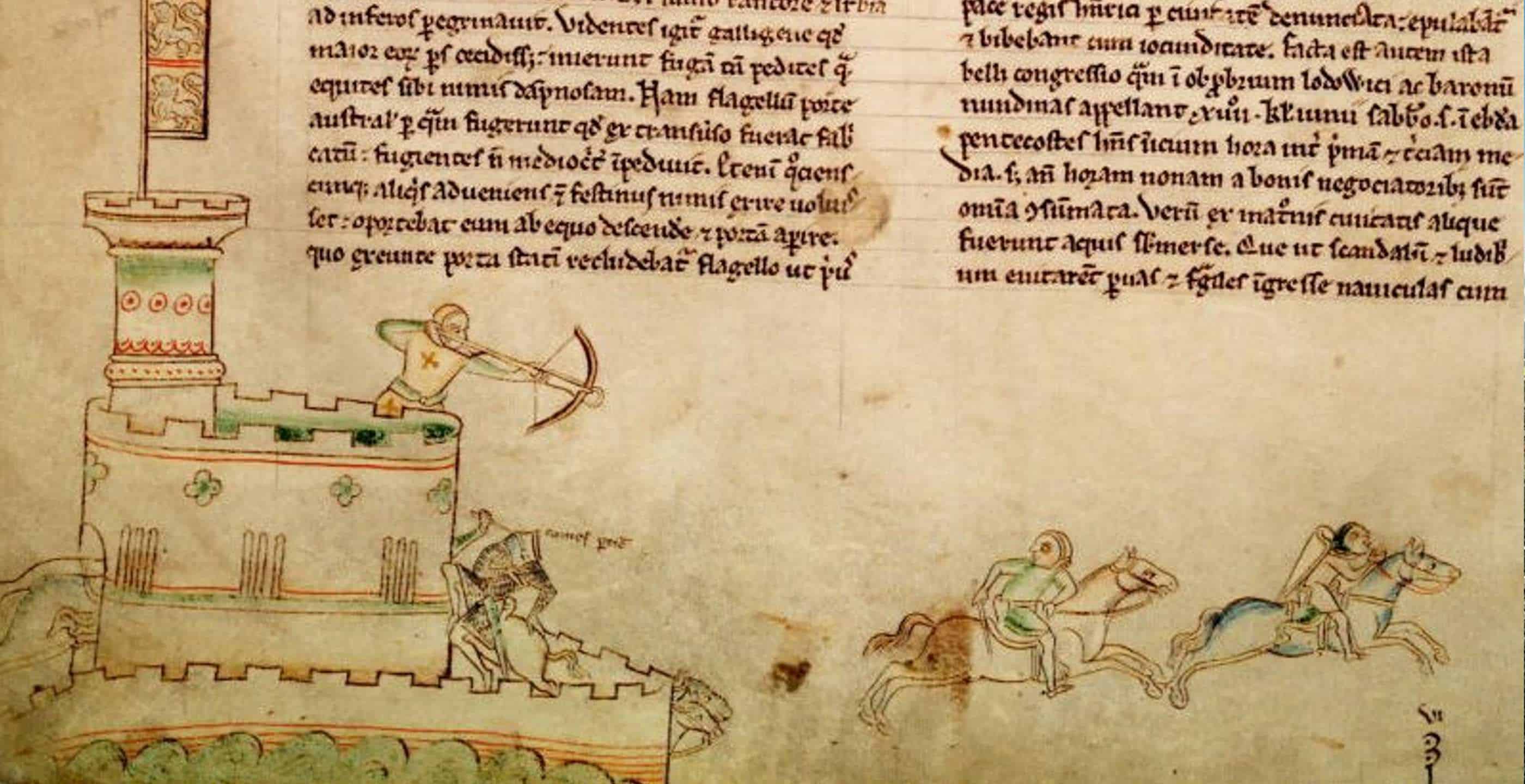

Despite him being considerably older, William Marshal served as protector to the king and successfully defeated the rebels at the Battle of Lincoln.

The battle commenced in May 1217 and served as a turning point in the First Barons’ War, with Marshal’s victorious army looting the city. Lincoln was known to have been loyal to Louis VIII forces and thus Henry’s men were keen to make an example of the city, catching French soldiers as they fled south as well as many of the treacherous barons who had turned against Henry.

In September 1217, the treaty of Lambeth enforced Louis’s withdrawal and ended the First Barons’ War, putting the animosity on pause.

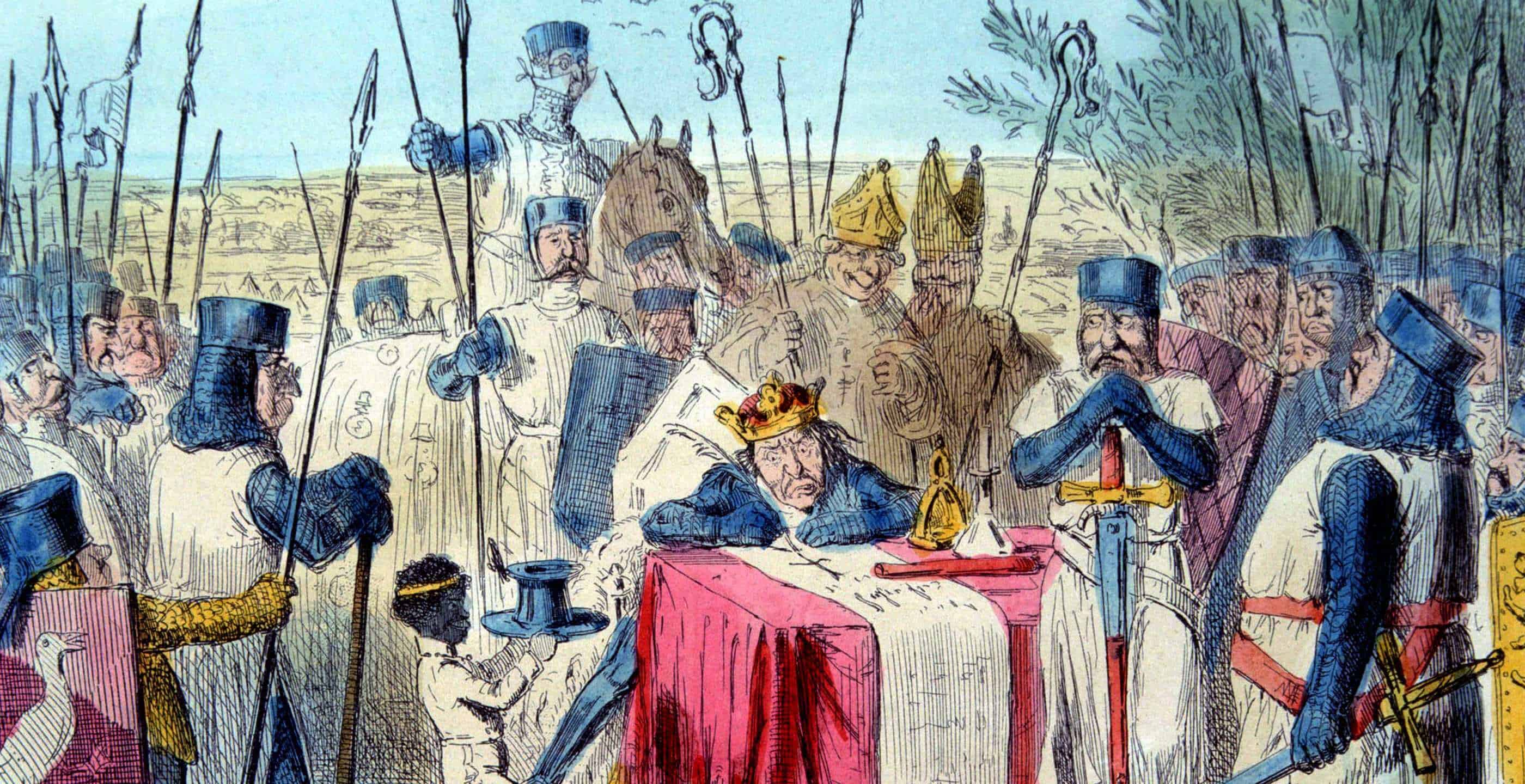

The treaty itself incorporated elements of the Great Charter which Henry had reissued in 1216, a more diluted form of the charter issued by his father King John. The document more commonly known as the Magna Carta was designed to settle the differences between royalists and rebels.

By 1225, Henry found himself reissuing the charter again, in the context of Louis VIII attack on Henry’s provinces, Poitou and Gascony. Whilst feeling increasingly under threat, the barons decided to support Henry only if he reissued the Magna Carta.

The document contained much the same content as the previous version and was given the royal seal once Henry had come of age, settling power-sharing disputes and ceding more authority to the barons.

The Charter would become ever more engrained in English governance and political life, a feature which continued in the reign of Henry’s son, Edward I.

With the Crown’s authority visibly limited by the charter, some more pressing baronial issues such as patronage and the appointment of royal advisors were still left unresolved. Such inconsistencies plagued Henry’s rule and subjected him to more challenges from the barons.

Henry’s formal rule only came into force in January 1227 when he came of age. He would continue to rely on advisers who had guided him in his youth.

One such figure was Hubert de Burgh who became highly influential in his court. Nevertheless, only a few years later the relationship would sour when de Burgh was removed from office and imprisoned.

Meanwhile, Henry was preoccupied with his ancestral claims to land in France which he defined as “restoring his rights”. Sadly, his campaign to win back these lands proved chaotic and frustratingly unsuccessful with an invasion in May 1230. Rather than invading Normandy his forces marched to Poitou before reaching Gascony where a truce was made with Louis which lasted until 1234.

With little success to speak of, Henry was soon faced by another crisis when Richard Marshal, the son of Henry’s loyal knight William Marshal led a revolt in 1232. The rebellion had been instigated by Peter De Roches, the new found power in government, backed by Poitevin factions in the county.

Peter des Roches was abusing his authority, navigating around the judicial processes and stripping his opponents of their estates. This led Richard Marshal, the 3rd Earl of Pembroke to call on Henry to do more to protect their rights as stipulated in the Great Charter.

Such animosity soon erupted into civil strife with Des Roches sending troops to Ireland and South Wales whilst Richard Marshal allied himself with Prince Llewelyn.

The chaotic scenes were only tempered by the intervention of the Church in 1234, led by Edmund Rich, the Archbishop of Canterbury who advised the dismissal of Des Roches as well as negotiating a peace settlement.

After such dramatic events had unfolded, Henry’s approach to governance changed. He ruled his kingdom personally rather than via other ministers and individuals, as well as choosing to remain in the country more.

Politics aside, in his personal life, he married Eleanor of Provence and went on to have five children. His marriage would prove successful and he was said to have remained faithful to his wife for their thirty-six years together. He also made sure she fulfilled a prominent role as queen, relying on her influence in political affairs and granting her patronage ensuring her financial independence. He even made her regent to rule whilst he was abroad in 1253, such was the trust he had in his wife.

Apart from having a supportive and strong relationship, he was also known for his piety which influenced his charity work. During his reign, Westminster Abbey was rebuilt; despite being low on funds, Henry felt it was important and oversaw its completion.

In domestic policy as well as international, Henry’s decisions had major ramifications none more so than his introduction of the Statute of Jewry in 1253, a policy characterised by segregation and discrimination.

Previously, in Henry’s early regency government, the Jewish community in England flourished with increased lending and protection, despite the protestation from the Pope.

Nevertheless, by 1258 Henry’s policies altered dramatically, more in line with those of Louis of France. He extracted huge sums of money from the Jews in taxation and his legislation ushered in negative changes which alienated some of the barons.

Meanwhile, abroad, Henry concentrated his efforts unsuccessfully on France, leading to another failed attempt at the Battle of Taillebourg in 1242. His efforts to secure his father’s lost Angevin empire had failed.

Over time his poor decision making led to a critical lack of funds, no more so than when he offered to finance papal wars in Sicily in exchange for his son Edmund being crowned king in Sicily.

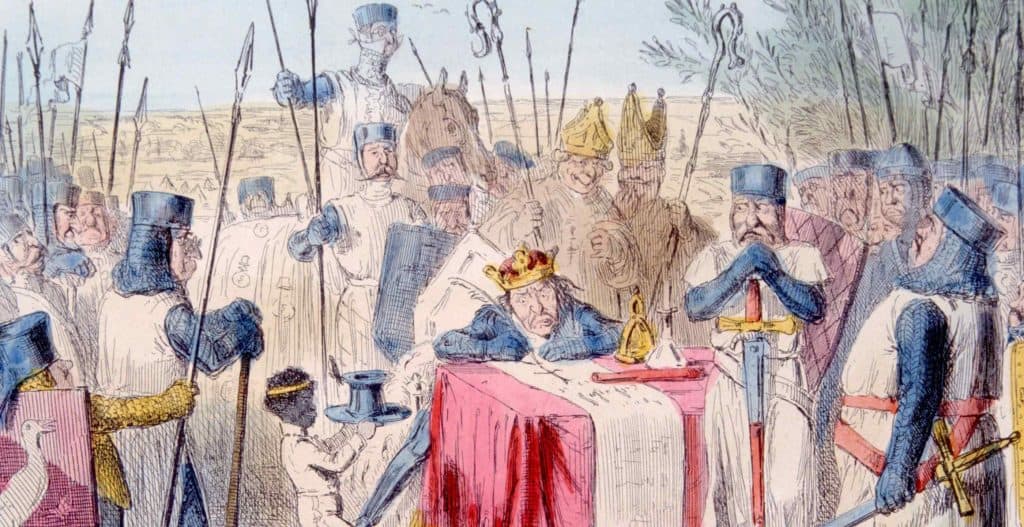

By 1258, the barons were demanding reform and initiated a coup d’etat, thus seizing power from the crown and reforming the government with the Provisions of Oxford.

This effectively ushered in a new government, abandoning the absolutism of the monarchy and replacing it with a fifteen member Privy Council. Henry had no choice but to take part and support the Provisions.

Henry turned instead to Louis IX for support, agreeing to the Treaty of Paris and a few years later, in January 1264, relying on the French king to arbitrate the reforms in his favour. By the Mise of Amiens, the Provisions of Oxford were annulled and the more radical elements of the rebel group of barons were ready for a second war.

Led by Simon de Montfort, in 1264 fighting had resumed once more and the Second Barons’ War was underway.

One of the most decisive victories for the barons occurred at this time, with Simon de Montfort the chief in command becoming the de facto “King of England”.

At the Battle of Lewes in May 1264, Henry and his forces found themselves in a vulnerable position, with the royalists overwhelmed and defeated. Henry himself was taken prisoner and forced to sign the Mise of Lewes, effectively transferring his power to Montfort.

Fortunately for Henry, his son and successor Edward managed to escape and defeated de Montfort and his forces in a battle at Evesham a year later, finally freeing his father.

Whilst Henry was keen to enact revenge, upon advice from the Church he altered his policies in order to maintain his much needed and rather ailing baronial support. Renewed commitments to the principals of the Magna Carta were expressed and the Statute of Marlborough was issued by Henry.

Now nearing the end of his reign, Henry had spent decades negotiating and withstanding direct challenges to his power.

In 1272 Henry III passed away, leaving a torrid political and social landscape for his successor and first born son, Edward Longshanks.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.