Henry VI was just nine months old when he came to the throne, an infant destined for power and glory but would he be able to live up to the task?

A contrasting figure to his father King Henry V, the new king was set to govern through a turbulent period, characterised by losing power in France and the ultimate descent into crisis culminating in the long-running dynastic dispute known as the War of the Roses.

His was a reign that was overthrown, restored and finally ended with murder.

Born in December 1421 at Windsor Castle, Henry was crowned king at Westminster Abbey in November 1429 and subsequently two years later at Notre Dame in Paris, as Henri II. Henry is the only English monarch to have been crowned King of France.

As he was still only an infant, a regency council was left to run the country until Henry came of age in 1437.

Whilst the young king grew up, he began to exhibit qualities which left him rather unsuited to the trials and tribulations which would befall a medieval king of Europe. He was known for his piety, generosity, avoidance of violence and docility: not the usual qualities of a king of this time.

It soon became clear that his simple ways and lifestyle would not suit the intense political wrangling of court with his inability to gain any semblance of control over his magnates. This was a man that differed quite dramatically from his father, for he could not master the goings on around him and his desire to avoid conflict was simply deadly in an era characterised by war.

Meanwhile, his marriage to Margaret of Anjou in 1445, Charles VII’s niece, was arranged with the desire for peace although such a union did not appear to dissipate the bad blood. Margaret, unlike her husband, was very strong-willed and exerted her influence over the king’s decisions on big policy matters, including when he handed the province of Maine over to the French crown.

Henry VI was an ineffectual ruler and his uncle, Charles VII contested his claims to the French crown.

Whilst his early reign had been well-managed by a group of people maintaining English power in France, in time ongoing challenges proved overwhelming as a host of problems presented themselves and threatened Henry’s position as king.

In 1435, the situation in France worsened when Burgundy, England’s traditional ally changed her allegiances and thus altered the distribution of power. At the same time, the famous and inspiring Duke of Bedford, brother of Henry V and Regent of France on behalf of Henry VI, died during the congress of Arras.

He had been a crucial military and political figure at the height of England’s success in France. The defection of Burgundy was the final straw and in 1436, Paris was in the hands of Charles VII.

In the next couple of decades, the French would consolidate their power, with the Dauphin and the charismatic Joan of Arc chipping away at England’s French possessions, leading to in 1450 to the loss of Normandy.

Not only was this a loss of territory but also a loss of prestige for the king and as such activities continued, so too did the political instability back at home in England.

Against a backdrop of growing French power, the king’s ability to rule came into question. Henry entrusted the power of his court to greedy power-grabbing magnates like William de la Pole, the 1st Duke of Suffolk, who governed the country in a disorderly and chaotic way.

Private armies would fight one another, rival groups warred between themselves and all the while, Margaret of Anjou consolidated her power as law and order came crashing down around the king.

The queen and her supporters in court were growing more powerful whilst Henry languished in the shadows. He was soon faced by accusations of mismanagement in government and wartime misconduct. This indictment came from none other than Henry VI’s cousin, Richard, Duke of York.

The friction was escalating, factions were becoming more visible and the divisions between those seeking peace and those determined to engage in war looked to be more engrained into the English court each day.

In the meantime, France was tightening its grip on England’s possessions, overrunning Gascony which had been in the hands of the English for centuries.

The losses incurred in France and the challenges to his rule led Henry to suffer a series of mental breakdowns and severe depression.

As Henry looked increasingly unstable, power struggles loomed between William de la Pole’s successor, Edmund Beaumont, the Duke of Somerset and Richard Duke of York. Somerset was a close personal friend and ally of Margaret of Anjou and his rivalry with Richard would soon escalate into war.

Meanwhile, another figure, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick would become instrumental. Known as “the kingmaker”, his grievances with Somerset would lead to his support of York. Only this was a fickle man whose support swayed between both camps before he met his own demise.

Richard of York, as a descendant of Edward III had a legitimate claim to the throne and those who supported his challenge to the crown became known as Yorkists.

Meanwhile, Margaret and her noble supporters represented the Lancastrians.

In 1454 York was given the title, “Protector of the Realm”, due to Henry’s worsening state. He used his position to purge the Lancastrian supporters in court and throwing Somerset into the Tower of London. Such action created deep animosity and upon the king’s temporary recovery, Richard of York was dismissed from his role.

Nevertheless, Yorkists and Lancastrians began to prepare for battle, recruiting soldiers and making preparations for war.

Whilst the English suffered defeat in the Hundred Years’ War, conflict was brewing domestically. To compound issues, the loss of land in France resulted in producing very irate landowners back in England.

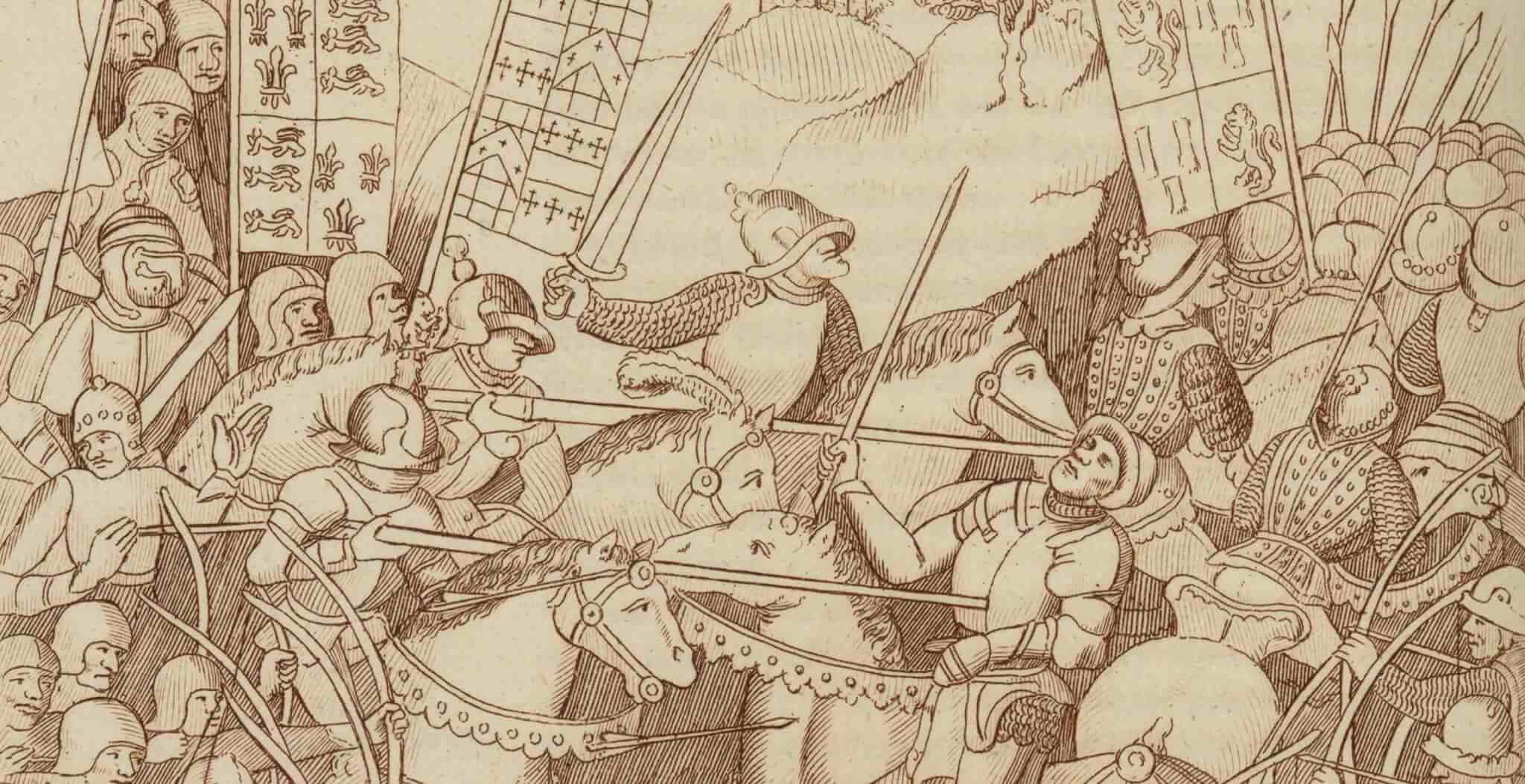

With a dynastic duel bubbling under the surface, it was only a matter of time before both sides engaged in real conflict. In 1455, only two years after one of the longest conflicts with France had concluded, civil war broke out in England, with supporters choosing either a Red Rose to represent Lancaster or White Rose for the House of York.

Brutality and bloodshed spilled out onto the fields of England, with the War of the Roses starting its first major battle in May 1455 and concluding with the Battle of Stoke Field in 1487.

Such a civil conflict led to a great loss of life on both sides with numerous battles securing victories, but not yet definitive for either the Yorkists and Lancastrians.

By July 1460, at the Battle of Northampton, another York victory resulted in the capture of Henry whilst his wife fled to safety in Wales. She would soon rally together an army in response to the news that Richard of York had declared himself heir to the throne.

Only months later however, Richard lost his life at the Battle of Wakefield and was succeeded by his son, Edward, the Earl of March who would go on to secure more victories for the Yorkist side.

Nevertheless, in the coming months, an important victory for the House of Lancaster precipitated a successful rescue of Henry VI. This did not however prevent Edward of York proclaiming himself king in London.

By the 29th March 1461 Henry VI had found himself deposed whilst Richard of York’s son Edward became Edward IV.

Like with any ongoing conflict, the numerous battles resulted in losses and gains for both sides and for Henry this was more personal than for anyone else. A war based on who would reign as monarch was a direct challenge to his authority; he found himself against stiff opposition and in 1465 was captured and placed in the Tower of London.

With the saga rolling on for several more years, Henry was able to reclaim his throne on one final occasion in 1470, only to have it taken away from him a year later by Edward.

At the Battle of Barnet in 1471, Warwick the Kingmaker was killed and one month later the Prince of Wales was killed and Queen Margaret was captured.

Having lost his heir and with his wife in captivity, Henry VI came to an untimely end in May 1471, murdered at the Tower of London.

Henry VI had led a life of an ineffectual king, precipitating the rise of animosity and challenges to the throne that found expression in the War of the Roses.

Under his reign, England’s prized possessions and territories in France were lost and the English found themselves at a crossroads both politically and militarily, a predicament that could only be solved by a dynastic duel.

Such a challenge would rage on long after Henry VI was gone, only reaching its conclusion with the union of the red and white rose, ushering in a new dynasty: the Tudors.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: January 28, 2021.