King James I succeeded the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, becoming the first Stuart king of England. He had already reigned as King James VI of Scotland for the last thirty-six years.

He was born in Edinburgh Castle in June 1566, the only son of Mary, Queen of Scots and Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. James’s royal roots were strong with both his parents’ being descendants of Henry VII of England.

His parents’ marriage was turbulent with his father forming a conspiracy to kill the Queen’s private secretary.

In February 1567, when James was not even one years old, his father was murdered and as an infant James inherited his titles. Meanwhile, his mother remarried only a few months later to James Hepburn, an individual suspected of having been involved in the murder plot.

Resentments and treachery were rife and the Protestant rebels soon arrested the queen and imprisoned her in Loch Leven Castle, forcing her abdication in July the same year. What this meant for the young James was that his half-brother, the illegitimate James Stewart, became regent.

James was only thirteen months old when he was anointed King of Scotland. The coronation ceremony was carried out by John Knox.

Meanwhile, James was brought up by the Earl of Mar at Stirling Castle. His upbringing was Protestant and his tuition was under the guidance of the historian and poet George Buchanan, who would instill in James a life-long passion for learning.

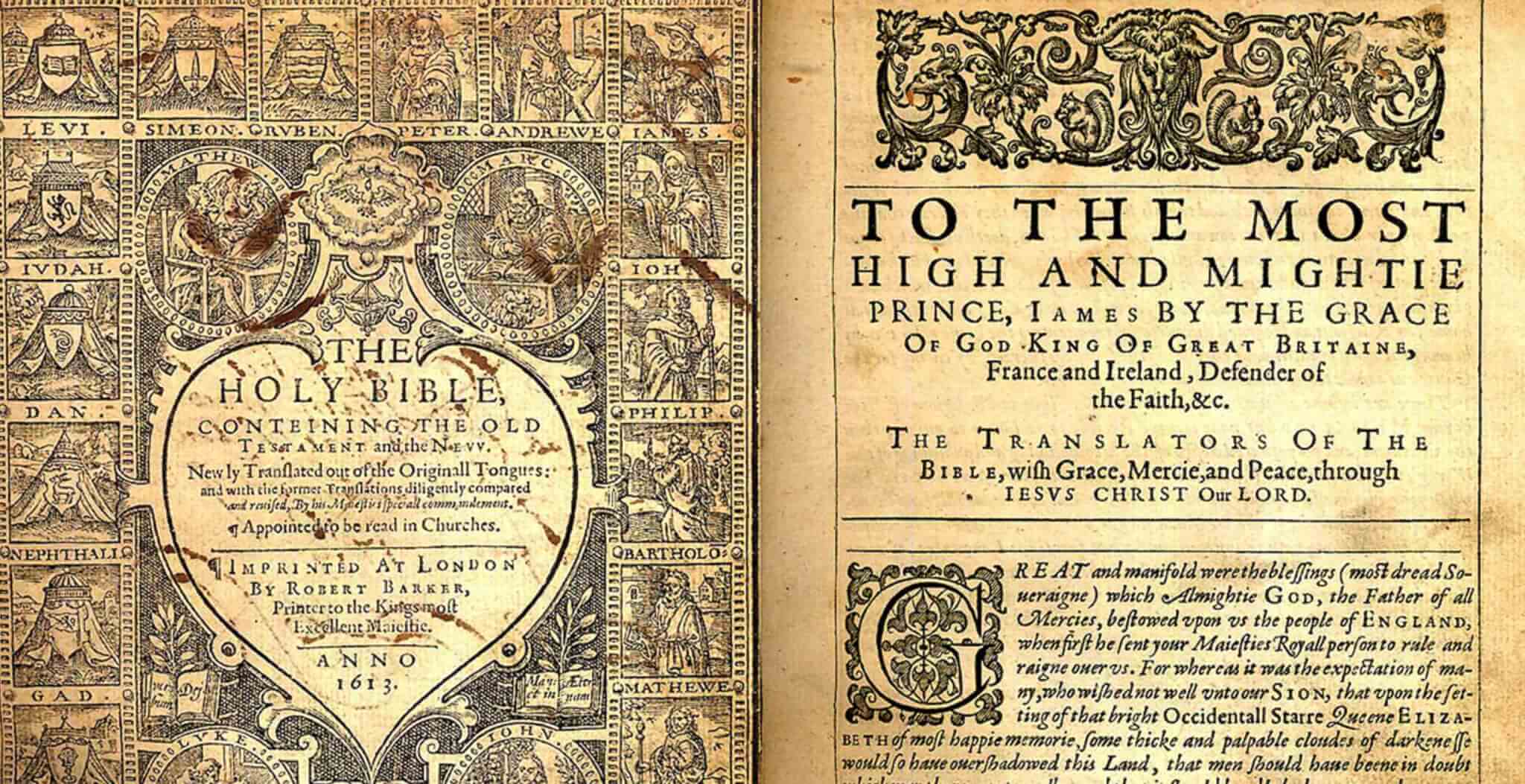

His education would hold him in good stead in later life, particularly literature, producing his own published works as well as sponsoring the translation of the Bible which would be named after him.

James was a king with real literary passion and unsurprisingly, during his reign, there was a Golden Age of Elizabethan literature with the likes of Shakespeare and Francis Bacon.

During his youth, a succession of regents would remain in control until James was older. In the meantime, he would fall under the influence of Esmé Stewart, the first cousin of James’s father Lord Darnley. In August 1581, he would make him the only Duke of Scotland, however this relationship was soon frowned upon, particularly by the Scottish Calvinists who in August 1582, executed the Ruthven Raid, whereby James was imprisoned and Stewart, the Earl of Lennox expelled.

Whilst he was imprisoned, a counter-movement soon had him released however the issues of the Scottish nobility would continue to ferment under ecclesiastical pressures.

With James now freed from the clutches of the rebel earls, in June 1583 he saw fit to take back control and reassert his authority, whilst also trying to balance the various religious and political factions.

During his early reign he attempted to achieve peaceful conditions with the assistance of John Maitland who was Lord Chancellor of Scotland.

Some attempt was also made at reforming James VI’s finances and an eight man commission called the Octavians was set up in 1596. Nevertheless, such a group was short-lived and a Presbyterian coup against them was triggered after suspicions of Catholic sympathies.

Such a volatile religious setting dominated and James VI experienced threats to his position, particularly in August 1600 when Alexander Ruthven supposedly assaulted the king.

Despite such challenges, James was determined to make headway, particularly with regards to the relationship between England and Scotland which was impacted by the signing of the Treaty of Berwick in 1586.

This was an agreement between James VI and Elizabeth I, essentially agreeing to an alliance based on defence as the two countries, now predominantly Protestant, had overseas threats from European Catholic powers.

James was motivated by the chance to inherit the throne from Elizabeth I, whilst in the meantime he would receive a generous pension from the English state. The writing was on the wall for James to succeed the throne.

Meanwhile, James’s mother Mary, former Queen of Scots, had fled south of the border to England and had been held in confinement for eighteen years by Elizabeth I. Only a year after the agreement between Elizabeth and James, Mary was found guilty of an assassination attempt and subsequently beheaded at Fotheringhay Castle with surprisingly little protestation from her son.

Whilst denouncing the act as “preposterous”, James had his eye on the English throne and it was not until he became King of England that her body would be interred in Westminster Abbey on his instructions.

Two years after his mother’s death, James embarked on a suitable marriage to Anne of Denmark, the daughter of Protestant Frederick II. The couple married in Oslo and went on to have seven children, with only three surviving until adulthood: Henry, Prince of Wales, Elizabeth who would become Queen of Bohemia and Charles, his heir, who would become King Charles I upon James’s death.

By 1603, Elizabeth I was on her deathbed and in March she passed away. James was proclaimed King of England and Ireland the following day.

Within a month James had made his way down to London and upon his arrival the people of London were eager to catch a sight of their new monarch.

On 25th July 1603 his coronation took place, an ostentatious affair which enveloped the city of London despite the ongoing plague.

King of England and Ireland as well as reigning monarch of Scotland, and as a believer in the divine right of kings, James now possessed more power, greater riches and was in a stronger position to enact his own decisions.

In this context however, suspicions were still rife on both sides; the Scots who now had an English king and the English who now had a Scottish king.

In his time as monarch he was faced with challenges, none more so than two plots in his first year, the Bye Plot and Main Plot which were foiled and led to arrests.

Of course, the most famous attempt against the king was executed by the Catholic Guy Fawkes, who one wintry November night planned to blow up Parliament using 36 barrels of gunpowder. Thankfully for the king, this plan was foiled and Fawkes alongside his co-conspirators were executed for their attempted crime. The 5th November was subsequently declared a national holiday, whilst anti-Catholic sentiment was stirred and James increased his popularity.

Meanwhile, James I left the governance and administration side of things to Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury whilst he focused on some of his bigger plans, most pertinently the idea of a closer union between England and Scotland.

His plan was simple, to have one united country under one monarch, following the same laws and under one parliament. Sadly for the king, his ambitions were met by lack of support on both sides as he misread the political situation.

In a parliamentary address given in 1604 he stated his case:

“When God hath conjoined them, let no man separate. I am the Husband, and all the whole Isle is my lawful Wife”.

He subsequently declared himself “King of Great Britain” although the House of Commons made clear its use in legal framework was not allowed.

By 1607 James managed to have repealed more hostile laws that had already existed between England and Scotland. Moreover, a new flag was now commissioned for all ships, commonly known as the Union Jack in reference to King James’s preference for his French namesake, Jacques.

Whilst inroads to a closer Anglo-Scottish union were being made, the Plantation of Ireland, begun by the Protestant Scottish community in 1611, did not help matters as it simply fuelled religious antagonisms already in existence.

Meanwhile across the continent, James fared better with his foreign policy of avoiding war, particularly, his involvement in the peace treaty signed between England and Spain in August 1604.

James clearly intended to avoid drawing Great Britain into conflict, although in the end, he could do very little to avoid involvement in the Thirty Years War.

As King of Great Britain he had vision and enough intellect to act on such ideas, sadly, his personal life did not help matters and in the end resulted in increasing resentment.

James I was homosexual and had favourites at court. In time he developed a number of infatuations with younger men, with the objects of his affection receiving titles and privileges as a result.

One of these figures was Robert Carr, a Scotsman who would, thanks to James’s affection, become Viscount of Rochester in 1611, followed two years later by elevation to the title Earl of Somerset.

Perhaps most famous was George Villiers whose rapid climb up the greasy pole was astounding and owed a great deal to the favouritism that was bestowed upon him. Known affectionately as “Steenie” by James I, he was made Viscount, then Earl of Buckingham, followed by Marquess and then Duke. Sadly for Villiers, he was to meet a sticky end when he was stabbed in 1628 by a madman.

Meanwhile, in the latter years of his reign James began to suffer ill-health, plagued by numerous conditions; in his last year he was seen very little. On 27th March 1625 he passed away, leaving behind an eventful reign as both monarch for Scotland as well as England and Ireland. Often well-intentioned, his desires did not always become a political reality but the avoidance of conflict, combined with closer alliances showed a desire for peace not seen in other monarchs.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: February 8, 2021.