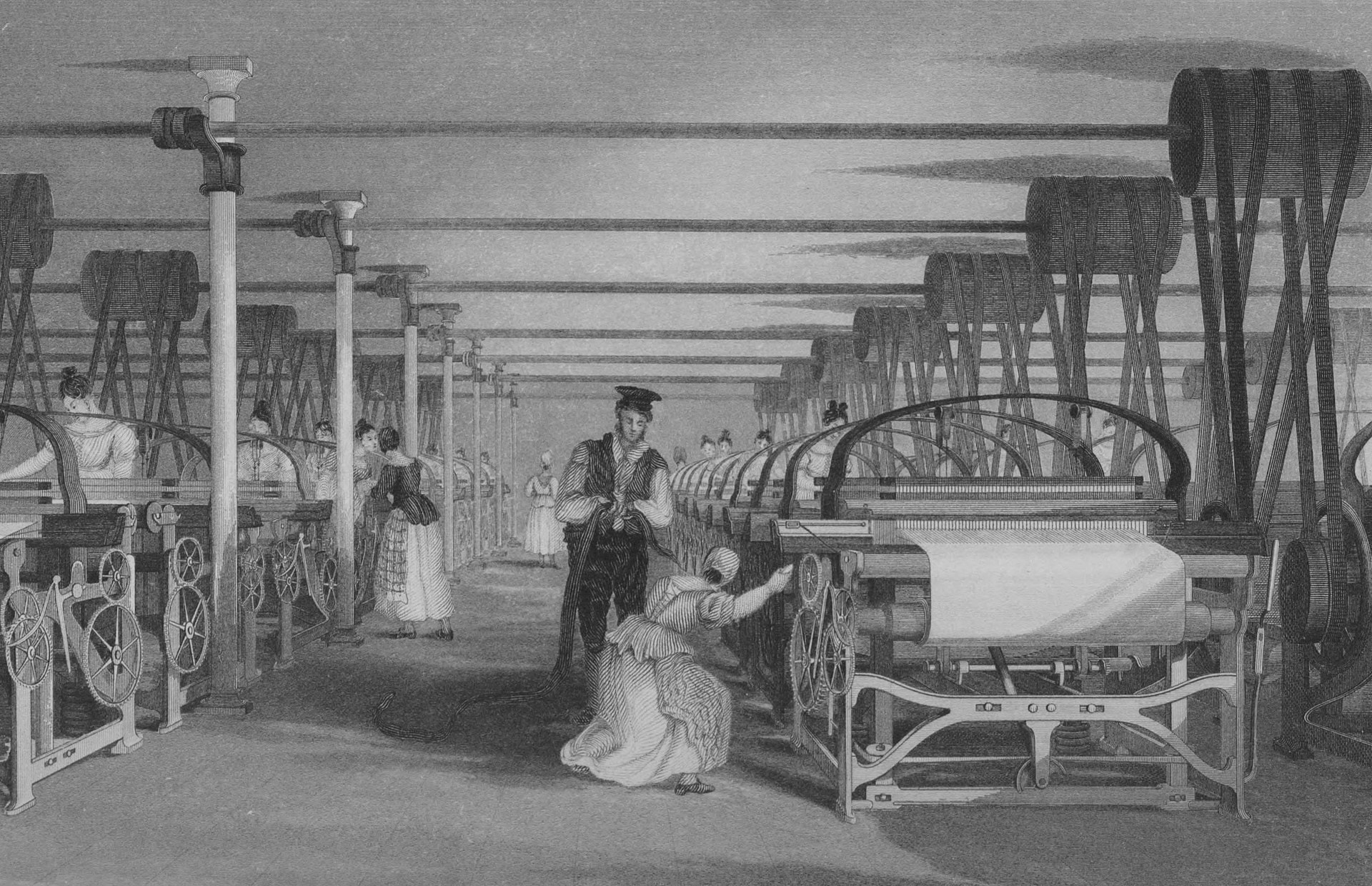

By 1825, cotton was Britain’s biggest import and the dominant force of the economy was the Lancashire cotton industry. It was this industry that experienced the advent of the Industrial Revolution for Britain; the move from small cottage industries, where family income was supplemented by weaving and spinning wool, towards a factory based production line using imports from across the world.

A social reorganisation occurred as a result of the new factory regime. It was the birth of the British working class; a barrier between those who owned the factories and those who worked in the factories was formed. The revolution also sparked industrialisation within rival countries; competition was impossible against the new factories with their dramatic increase in yields.

Lancashire had the optimum conditions for a cotton explosion; a climate that prevented the cotton fibres splitting, water sources to power the mills that ran the factories (and then coal supplies as technology progressed), a willing work force and creative entrepreneurs with the vision and drive to construct the new regime. Raw cotton was imported into the country, mainly from the American cotton fields. Factories in the south of Lancashire spun the threads and the weaving of vast cloths occurred in the towns to the north (with Blackburn at the forefront). This system was capable of supplying the enormous demand of the Indian population: “dhootie”, cheap cotton loincloth, clothed the nation. And so Lancashire became known as the “Workshop of the World”.

Production continued to increase and the industry expanded right up until the First World War, with the exception of 1861-1864, the time of the American Civil War.

The exact reasons for the onset of war between the northern and southern states are disputed but the action that sparked depression overseas was the blockade of the southern ports by Federal Navy. This cut off the supply of raw cotton to Europe, including Lancashire. At the start of this depression, Lancashire mills had a four month supply of cotton already stockpiled. The impact didn’t hit immediately though, so they had enough time to stockpile another month. Initially, the war was not thought to last long so this was thought to be sufficient to get through the dry spell. But we all know that wars are not settled simply and the cotton supply soon ceased entirely.

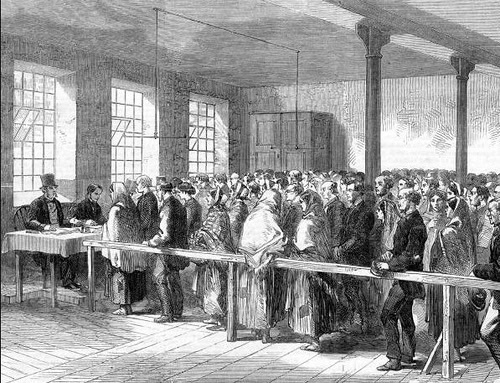

Without raw materials, production was terminated by October 1861; mill closures, mass unemployment and poverty struck northern Britain (soup kitchens were opened in early 1862). The stocks of raw cotton were held in warehouses throughout Lancashire, the merchants depending on rising prices, sometimes shipping back to America (e.g. New York) when the prices were favourable.

Relief was provided by the British government in the form of benefits; tokens were distributed to a specific value and were handed to traders so that goods could be exchanged to that amount. Emigration to America was offered as an alternative; agents came to recruit for the American cotton industry and also for the Federal army. Workers also made the shorter move to Yorkshire for work in the woollen mills there. Blackburn alone lost approximately 4000 workers and their families.

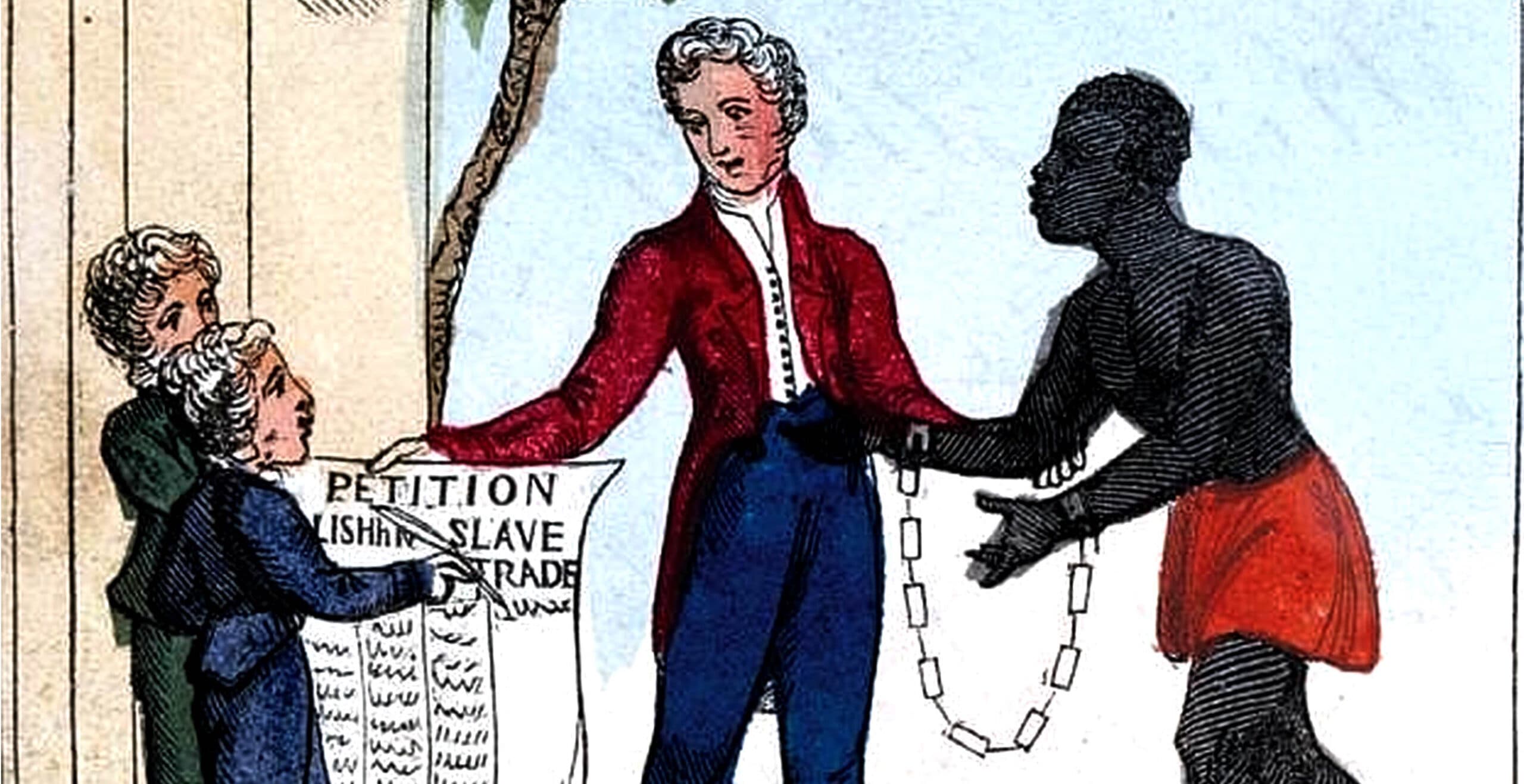

It was hoped in America that Europe (other countries like France were affected too) would intervene in their Civil War and force the Union to make peace. However, an intervention that helped the southern states would have been an intervention that supported slavery.

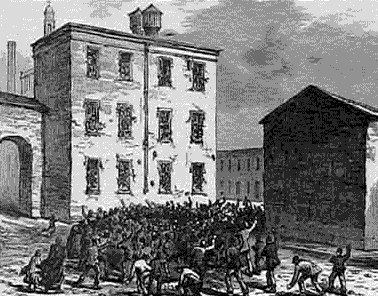

On 31st December 1862, cotton workers met in Manchester and concluded to support the Union in its fight against slavery, despite their own impoverishment. This peaceful and proud decision to side with Abraham Lincoln did not mean that Britain did not experience unrest. The advent of the class system in Britain that accompanied industrialisation gave rise to feelings of resentment between the workers and the masters of the mills. The working classes felt bitter at the controlled and nominal relief provided for them by the government. It was also resented that relief provided outside of the government came from affluent donors residing outside Lancashire, not from their own wealthy cotton masters. It was also felt that no distinction was made between those who were previously hardworking and forced into unemployment and those who were “stondin paupers” or drunkards.

This built up bitterness and resentment was released in several riots across the region; Stalybride, Dukinfield and Ashton saw riots in 1863. As a result, government relief was changed and instead provided in the form of constructive employment in urban regeneration schemes, implemented by local government, which at least made the local councils happy!

In conclusion, it was the slavery of fellow men and the globalisation of trade and reliance on the stability of other nations that played a major part in the downfall of the first industry in Britain.

Published: 14th March 2015