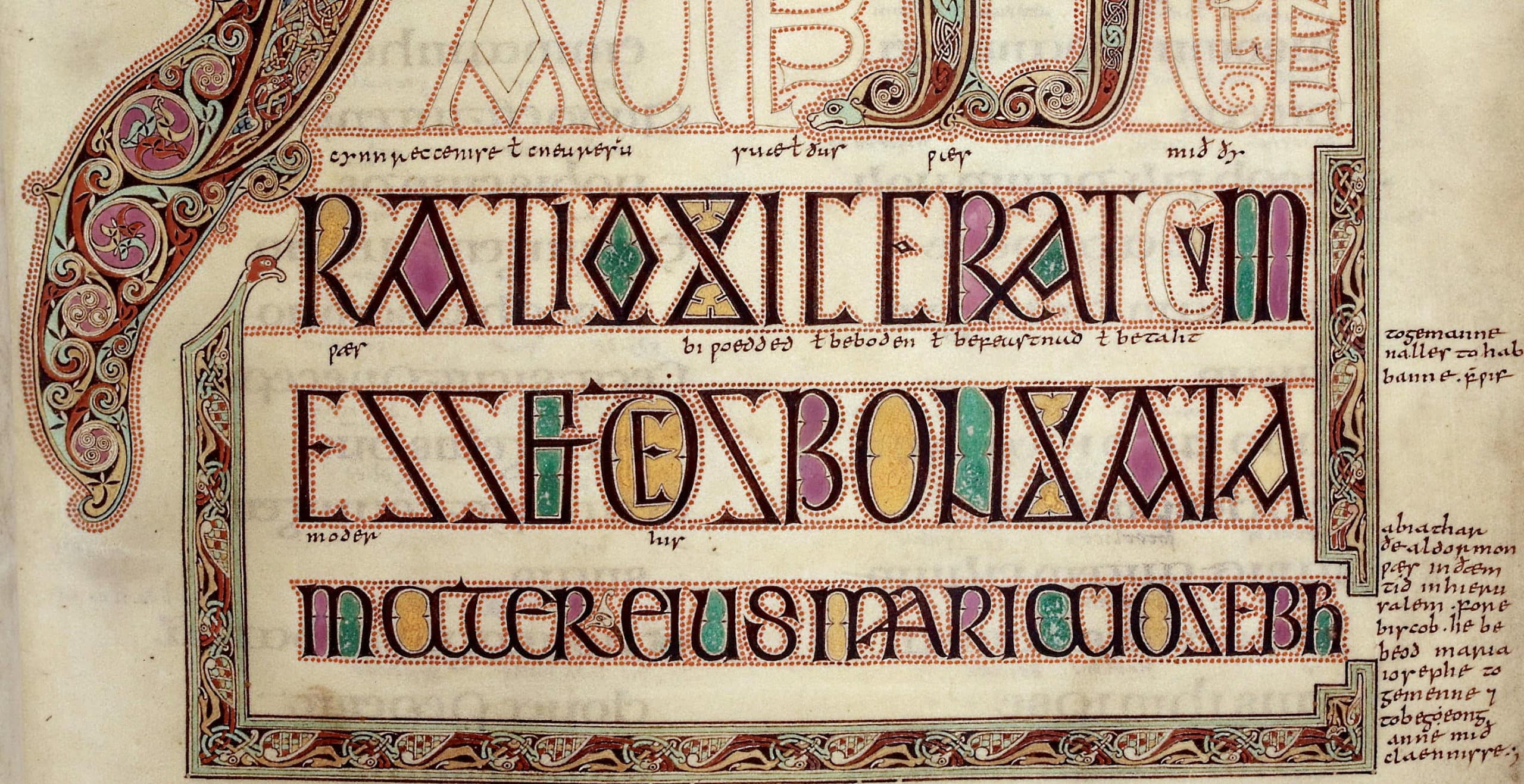

A famous illuminated manuscript created around 700 AD, the Lindisfarne Gospels is a historical marvel which demonstrates Anglo-Saxon art, culture and religious expression.

The creation of the text occurred on Lindisfarne around 1300 years ago and has since become famous for its beauty, ornate detail and design.

More commonly referred to as Holy Island, Lindisfarne was settled by Aidan and a group of Irish monks who had been invited to establish a monastic community there by King Oswald of Northumberland. They would come to develop, influence and represent the Celtic and religious traditions of the day.

The island itself, which lies only sixty miles away from the hustle and bustle of Newcastle, can at times of high tide be completely cut off from the mainland.

On this rugged and beautiful coastline, the evolution of Christianity in Northumbria developed, with King Oswald of Northumberland wishing the people to embrace the faith, letting go of the more pagan customs which had dominated.

Over time, the island of Lindisfarne was to have sixteen bishops, the first of whom was Aidan, whilst the most famous was Cuthbert. St Cuthbert was born in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, today’s Scotland in a time when the conversion to Christianity was taking place.

It was said that Cuthbert found his calling after seeing a vision on the night that St Aidan, the founding father of Lindisfarne, died.

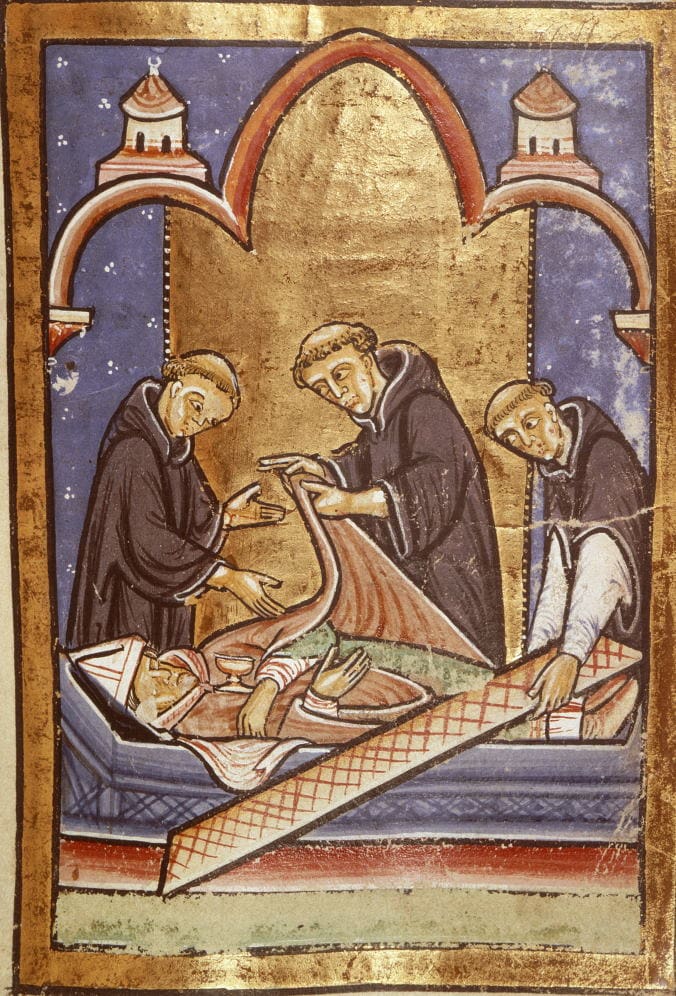

He would spend the rest of his life serving the church as a monk and a bishop. Whilst at Lindisfarne he played an important role in the evolution of monks’ practices. He would live the rest of his days out in solitude as a hermit before passing away in 687.

Eleven years later, when monks opened his tomb they were said to be astounded that his remains were untouched by decay. It was at this time, that his reputation grew. St Cuthbert’s shrine brought an increase in power, funding and popularity to the monastery. Lindisfarne was firmly on the map as a site of pilgrimage and epicentre of Christianity in the region.

St Cuthbert is referred to as the patron saint of Northumbria with a feast day held in his honour.

Since the time of its founding with St Aidan, Lindisfarne had become an important focal point for Celtic Christianity, however this peace and tranquillity was not to last. After its initial settlement, Lindisfarne was plundered by the marauding Vikings in 793, the group sacking the church and killing several monks.

After continued fears for their safety, the monks eventually made the choice to flee with the body of St Cuthbert, relics and books, one of them being the Lindisfarne Gospels.

As they fled to Durham in 995, the Holy Island was left to rack and ruin for almost two hundred years until William the Conqueror forced the monks to return once more to the solitude of the island.

The passing of Viking and Norman conquests eventually allowed the priory to be re-established with a small castle later being built on the island. The heyday of the island however had long since passed with the times of St Cuthbert and the monastery’s place in Christian history and culture.

It was around the early 700’s that an artistic masterpiece was produced, known as the Lindisfarne Gospels, containing a copy of the Gospels according to the four disciples, recounting the life of Jesus Christ.

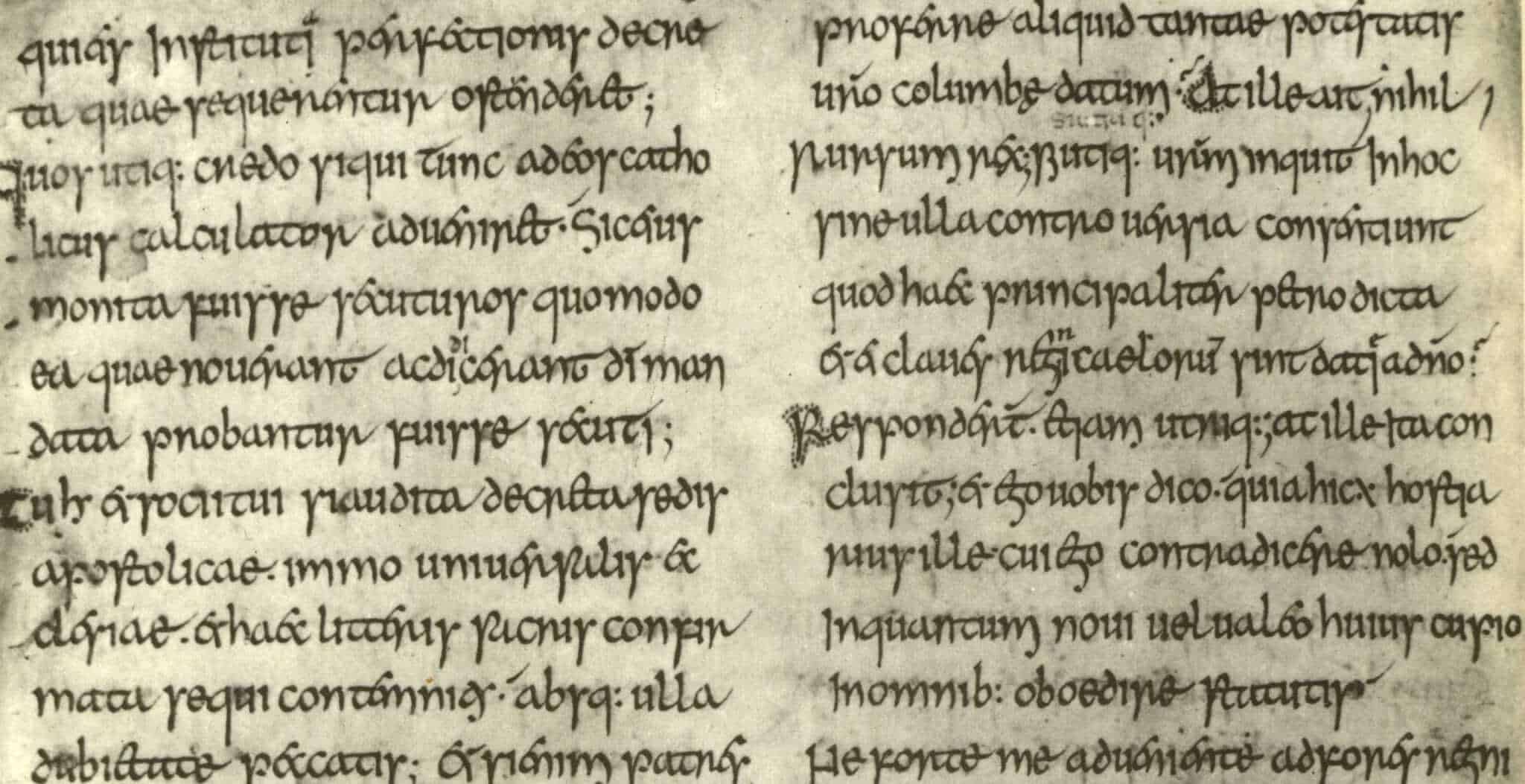

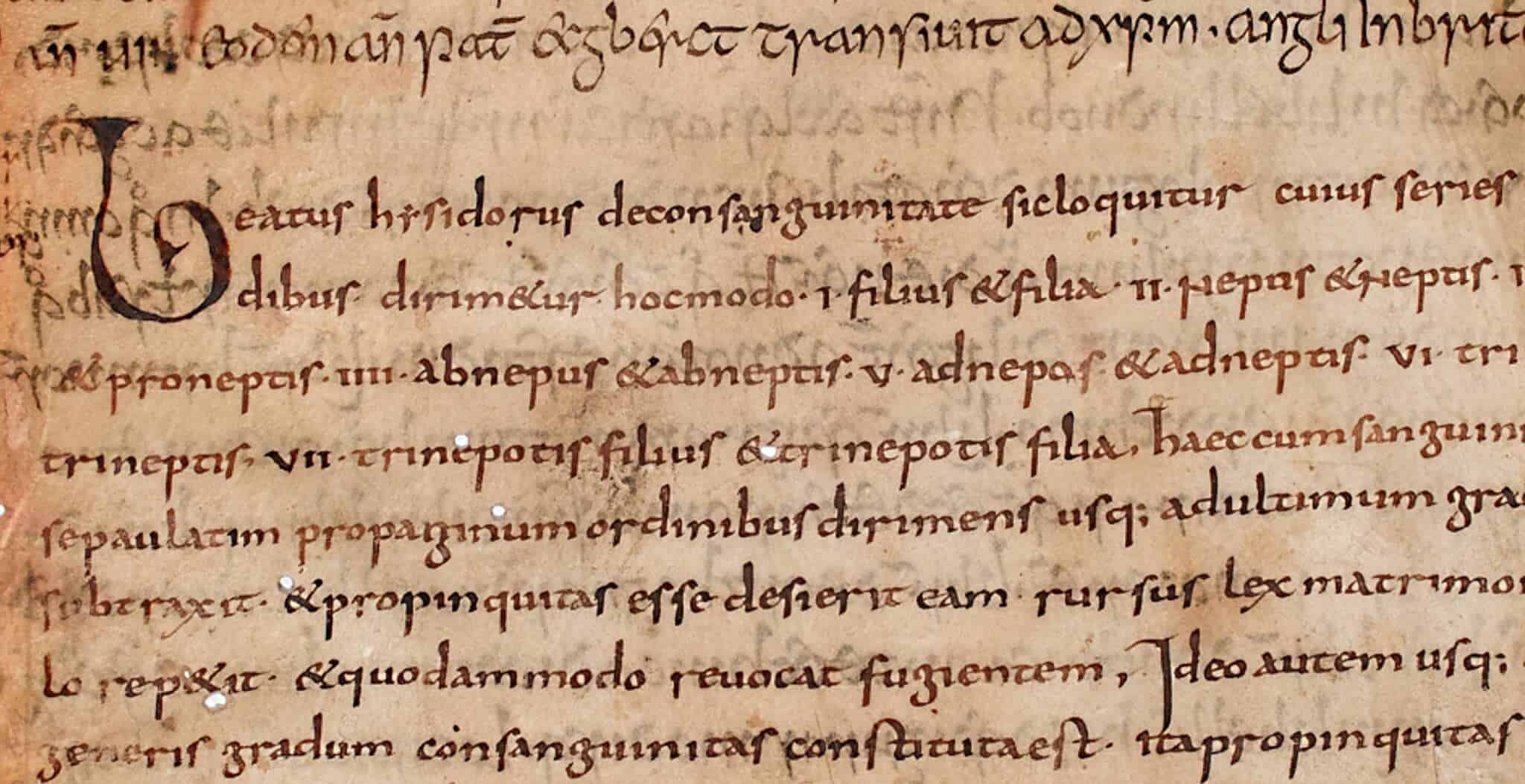

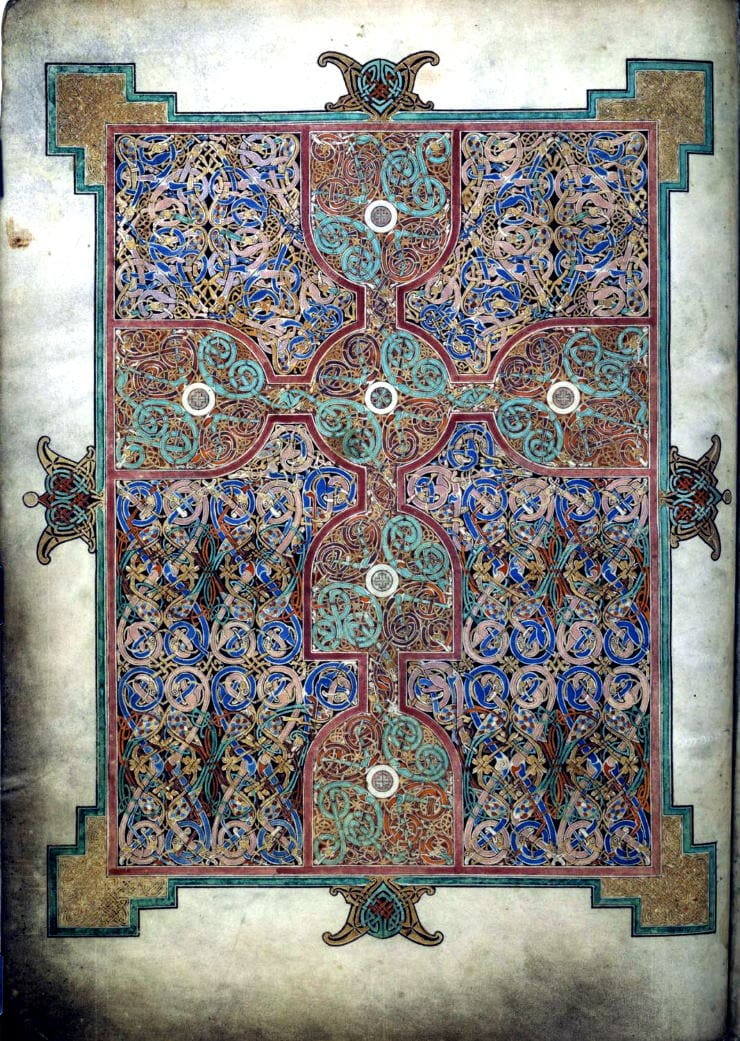

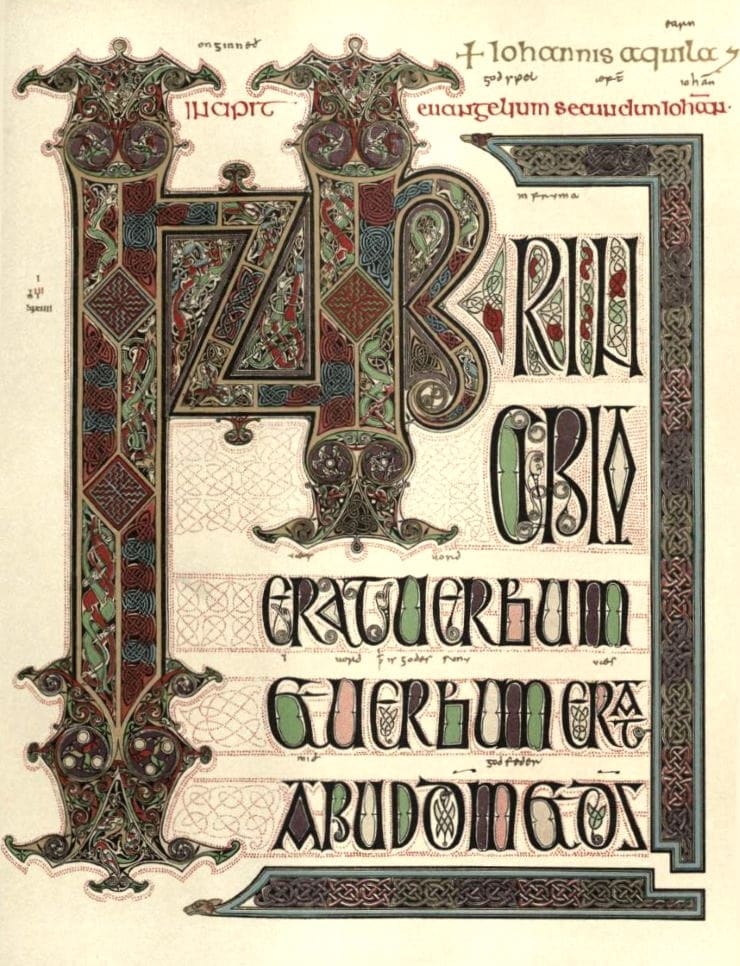

The manuscript is an ornate representation of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship which in itself belies the multitude of cultural and religious influences which contributed to its beauty. The Latin gospel text is presented with calligraphy and elaborate carpet pages, described as such due to the designs being reminiscent of Persian carpet design.

The use of carpet pages is typical of the form of illuminated manuscript represented by the Lindisfarne Gospels and can be found in other texts such as the Book of Kells and Book of Durrow. These beautiful pages are filled with decorative, geometric patterns and ornate, complex, colourful and often symmetrical motifs. It has been said that the inspiration could be taken from oriental, eastern textile or even Roman mosaic design and form.

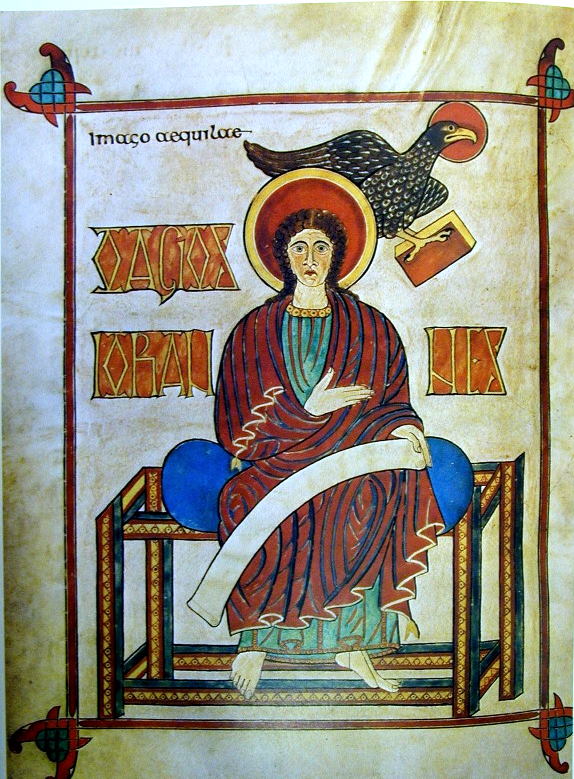

These elaborate Coptic-inspired carpet pages form the incipit pages before each Gospel. There are also artistic depictions of the four Evangelists which take inspiration from more Italian imagery.

Meanwhile, the metalwork features swirling patterns and design representing the strong Celtic artist traditions of Britain at the time. Interwoven patterns draw on monastic, artistic and cultural traditions, all contributing to the beauty of the text.

The Lindisfarne Gospels, with its elements of artistry from other cultures, is therefore even more noteworthy, not only as an item of Celtic and local Northumbrian heritage but as a representation of early multiculturalism.

This was a time of great change in the world with religious forms of expression changing and great shifts in behavioural patterns. As people travelled and expanded their horizons, cross-cultural connections were being formed, making this early medieval period a time of cosmopolitanism.

Moreover, there are historic references to the Celtic church and its relationship with Egypt, most notably in a letter written by the English monk Alcuin to Charlemagne in which he described the Celtic Culdees (Christian community) as Children of Egypt (pueri Egyptiaci). Therefore the works of Lindisfarne and others like it reflect the inspiration that Celtic monasticism took from a wide array of styles combining influences from far flung places such as Rome and Egypt.

The manuscript itself would have likely been used for ceremony and aside from its early binding being lost during Viking raids, the Lindisfarne Gospels has remained largely intact.

With much mystery about the origins of such a creation it is believed that the man responsible for such a work of genius was Bishop Eadfrith whilst two others, Brother Aethilwold and hermit Billfrith the Anchorite contributed to much of the binding and encasing of the book in metalwork and jewels.

“Eadfrith bishop of the Church of Lindisfarne

He, in the beginning, wrote this book for God and

St Cuthbert and generally for all the holy folk

who are on the island.

And Æthilwald bishop of the Lindisfarne-islanders,

bound and covered it without, as he well knew how to do.

And Billfrith the anchorite, he forged the

ornaments which are on the outside and

bedecked it with gold and with gems and

also with gilded silver-pure wealth.”

These words are taken from the priest Aldred who was responsible for adding later additions to the manuscript in the tenth century.

The artistic traditions represented by the monks on Lindisfarne point to the moment of conception for an exciting period of medieval English art which brought with it artistic cultural influences from the east combined with Celtic iconography of the British Isles.

Moreover, the Lindisfarne production of the gospel book in a spiritual and religious context also represented a great feat of dedication, perseverance, piety and devotion. The devout belief in the word of God and the importance of disseminating his message is yet another element of significance.

The beautiful text after its completion was faced with continued challenges and went on a vast journey across the British Isles with monks searching for a place of safety.

By the time of William the Conqueror, the Lindisfarne Gospels had found a new home in Durham Cathedral alongside the shrine of St Cuthbert. This resting place however was not to last as many centuries later, with the introduction of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, the book was taken to the Tower of London.

Two centuries on, the Gospels manuscript was in the personal ownership of a collector called Sir Robert Cotton who, after his death, left the nation this wonderful artifact at the British Museum.

Eventually by the late twentieth century, after a new binding was commissioned, the book found its final resting place, not in Northumberland but in the British Library where it is carefully housed today.

Wherever it may be housed, the Lindisfarne Gospel is not bound by geography for it is a treasure of a period of history, of a time, culture and peoples which shall be admired for many more centuries to come.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: March 8, 2021.