Since the last known sighting of Royal Navy frogman Lionel “Buster” Crabb on 19 April 1956 at the height of the Suez Crisis, his mysterious disappearance has led to theories of murder, espionage and Government cover-ups.

But 56 years later are we any closer to knowing the truth?

Born in Streatham, South West London on 28 January 1909 to Hugh Alexander a travelling photographic salesman and his wife Beatrice, Crabb came from very humble beginnings. When he left school Crabb held a series of menial jobs before serving as an army gunner at the outbreak of World War II.

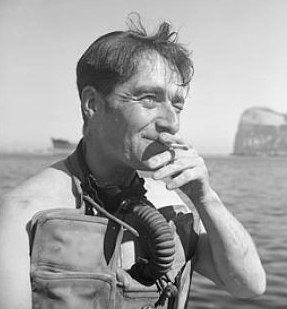

However, it wasn’t until Crabb joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve in 1941 that he discovered his passion and skill for diving. Crabb became part of the Royal Navy’s new diving unit, which was sent to Gibraltar to remove the unexploded limpet mines attached to the hulls of a number of Allied vessels. The task was very difficult and dangerous but one at which Crabb became extremely proficient. So much so, that in recognition of his bravery and diving prowess his colleagues nicknamed him ‘Buster’ after the American Olympic swimmer and action hero Buster Crabbe, who’s most popular roles included Tarzan and Flash Gordon.

However, it wasn’t until Crabb joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve in 1941 that he discovered his passion and skill for diving. Crabb became part of the Royal Navy’s new diving unit, which was sent to Gibraltar to remove the unexploded limpet mines attached to the hulls of a number of Allied vessels. The task was very difficult and dangerous but one at which Crabb became extremely proficient. So much so, that in recognition of his bravery and diving prowess his colleagues nicknamed him ‘Buster’ after the American Olympic swimmer and action hero Buster Crabbe, who’s most popular roles included Tarzan and Flash Gordon.

Crabb’s bravery during the war was recognised with a George Medal and he was also promoted to lieutenant commander in charge of all mine removal operations on the Italian coast. When the war ended Crabb received an OBE, and whilst he left the Navy shortly afterwards he remained in close contact with his military comrades, assisting with a number of naval projects.

Crabb the spy

It was not until 1955, when the Cold War was well under way, that Crabb engaged in his first covert mission. He was enlisted to undertake a number of secret dives around the Soviet ship Sverdlov, which was docked in Portsmouth harbour during an international naval review, alongside his diving companion Sydney Knowles, with whom he had served in Gibraltar. Knowles has since stated that they had been tasked with investigating the hull of the ship, which contained a large propeller designed to give the ship advanced manoeuvrability and speed. In March 1955, Crabb’s age and less than healthy lifestyle (he was said to be extremely fond of both cigarettes and alcohol) precluded him from professional diving and he was forced to retire. A year later he was allegedly recruited by MI6.

Crabb’s final mission

In April 1956, the Russian ship Ordzhonikidze docked in Portsmouth, bringing the current and successive Premiers of the Soviet Union, Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev on a good will visit to Britain in the midst of the Suez crisis. Britain and Egypt were locked in a disagreement over the ownership of the Suez Canal and the Russians had been providing weapons to the Egyptians, which meant it was important for Britain to keep relations with Russia as amicable as possible. However, shortly afterwards Khrushchev angrily called a halt to proceedings, alleging that his ship had been under surveillance by British intelligence.

On 29 April 1956, in a supposedly unrelated incident, the Admiralty reported Crabb missing, presumed dead. It was claimed that he had been “specially employed in connection with trials of certain underwater apparatus” at Stokes Bay on the Hampshire coastline, a few miles away from Portsmouth. Less than a week later on 4 May, the Russians complained to the Foreign Office that the crew of the Ordzhonikidze had seen a ‘frogman’ or combat diver in the water near their berth at Portsmouth harbour, plunging Britain into an almighty international incident which remains unsolved to this day.

What we do know – following the release of a number of classified documents in 2006 – is that on 17 April 1956, Crabb and another man identified as “Matthew Smith” but believed to have been Ted Davies, a navy liaison official from MI6, checked into the Sally Port Hotel in Old Portsmouth. The men had been recruited to investigate equipment in the stern of the Ordzhonikidze by Nicholas Elliott, an MI6 intelligence officer. On 19 April, Crabb and his companion took a small boat out into Portsmouth Harbour and Crabb made a successful preliminary dive next to the Ordzhonikidze. Crabb returned to the boat to brief his companion and to pick up an extra pound of weight for his next dive, from which he never returned.

“Mr Smith” returned to the Sally Port Hotel later that day to settle their bill and remove all of their belongings. The hotel register was also noted as having several pages removed on the days surrounding their stay.

Shortly before his disappearance, Crabb was also said to have been short of money and allegedly told friends that he was “going down to take a dekko at the Russian bottoms” for a fee of 60 guineas, ‘dekko’ being British forces slang for ‘taking a quick look’.

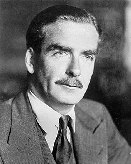

When questioned in the House of Commons, Britain’s Prime Minister at the time Sir Anthony Eden (pictured right), only added to the mystery surrounding Crabb’s disappearance when he stated that “It would not be in the public interest to disclose the circumstances in which Commander Crabb is presumed to have met his death.”

When questioned in the House of Commons, Britain’s Prime Minister at the time Sir Anthony Eden (pictured right), only added to the mystery surrounding Crabb’s disappearance when he stated that “It would not be in the public interest to disclose the circumstances in which Commander Crabb is presumed to have met his death.”

However, Eden made it clear that Crabb’s supposed spying mission had most definitely taken place without his knowledge or consent: “While it is the practice for ministers to accept responsibility, I think it is necessary in the special circumstances of this case to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty’s ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken.”

In what many saw as Eden’s retaliation to the flagrant disregard of his orders, the Head of MI6, Sir John Sinclair, left soon after the ‘Crabb affair’ – ostensibly taking early retirement – and was replaced by the previous head of MI5, Dick White.

Indeed in a letter to Lord Cilcennin, one of his closest advisers, which was made public in 2006, Eden stated that “It was the Naval Intelligence Department who asked that efforts should be made to obtain it [information about the Russian warships] while the Russian warships were in Portsmouth. NID knew of my direction that nothing of this kind should be done on this occasion.”

Just over a year later, on 9 June 1957, the body of a diver was found floating near Pilsey Island in Chichester Harbour. Conveniently the body was missing its head and both hands – the only way to clearly identify a corpse in the Fifties. Neither Crabb’s ex-wife nor his girlfriend were able to positively identify the body but Sydney Knowles’ assertion that Crabb had a similar scar on his left knee was enough for the coroner to conclude that the body was Crabb, although the cause of death could not be determined.

The numerous theories

Despite the fact that there has been little conclusive evidence, a number of theories have arisen regarding Crabb’s disappearance and supposed demise.

The state of the corpse discovered in Chichester Harbour led some to believe that Crab had been decapitated by the propellers of the Ordzhonikidze, while others believed he had been captured, killed or brain-washing by the Russians. It was even suggested that he had defected as a double agent or to join the Russian Navy. Indeed Tim Binding, the author of the 2005 book Man Overboard a fictional account of Crabb’s life, alleges that he was contacted by Sydney Knowles after the book was published and Sydney told him that Crabb had intended to defect and that MI5 had become aware of his plans. Had the popular British war hero become a Soviet citizen it would have been a PR nightmare of epic proportions. As a result, Knowles alleged that the Ordzhonikidze mission using an ageing, retired diver was actually arranged as a way to assassinate Crabb using a buddy diver to do the deed. Knowles himself was ordered to falsely identify the corpse as Crabb by MI5 and remain silent about what he knew.

Whilst the Russian Government may also have stayed silent on any link they may have to Crabb’s disappearance, in 1990 a former member of Soviet Naval intelligence, Joseph Zwerkin, alleged that the Ordzhonikidze’s crew had noticed Crabb in the water and he was promptly shot and killed by a Soviet sniper.

Even more sensationally, a 74 year old retired Russian diver by the name of Eduard Koltsov came forward in 2007 to clear his conscious and confess to Crabb’s murder. The then 23 year old Koltsov said that he had slashed Crabb’s throat in an underwater fight after observing him attaching a mine to the Ordzhonikidze and watched his body float away. Koltsov even showed a Russian documentary team the very dagger he had used and the Red Star medal he was allegedly awarded for doing the deed. Whilst it would be a very risky strategy it’s possible that Crab may have been affixing surveillance equipment to the ship. However, it seems extremely unlikely that Crabb would have been asked to bomb a Soviet ship during peace talks – which surely would have spelled disaster for Britain. It was also suggested that Koltsov’s attack of conscious arrived at a convenient time to discredit the recently released book about the Crabb affair, entitled The Final Dive.

More prosaically, but certainly more convenient for the Government and intelligence services, Nicholas Elliott reasoned that Crabb’s age and unhealthy life style were the reason for his disappearance, stating that Crabb “almost certainly died of respiratory trouble, being a heavy smoker and not in the best of health, or because some fault developed in his equipment”. However, Elliott’s connections with the Cambridge five, a spying ring who provided information to the Soviets during World War II, would have meant he was ideally placed to arrange a defection if required.

Even more interestingly, the Government made the decision to extend the Freedom of Information Act by a further 60 years in relation to the Cabinet papers on Crabb, which means we won’t know the truth until 2057, when all of those involved in Crabb’s disappearance will be long dead.

The Inspiration for Britain’s best loved spy?

Crabb has often been credited as inspiring Ian Fleming to create Britain’s most beloved MI6 agent, James Bond, and it was common knowledge that through his role as a naval intelligence officer Ian Fleming became friendly with Nicholas Elliott and was said to have been captivated by Crabb’s mysterious disappearance.

Like Bond, Crabb stood out from the crowd. A completed eccentric, Crabb often donned a monocle and carried a silver-mounted swordstick with a crab shaped handle, which was even buried with his supposed remains in 1957.

Indeed, Crabb’s final dive can certainly be seen as the inspiration for the novel and subsequent film Thunderball. Bond, also an extremely proficient diver, searches for atomic bombs hidden in the hull of the SPECTRE agent Emilio Largo’s ship the Disco Volante and engages in an underwater battle with enemy frogmen. Incidentally, Thunderball also went on to become the most financially successful film in the Bond franchise.

However, that’s where the similarity ends. Unlike the lithe and fit Bond, in 1956 Crabb was middle-aged and his health was declining. Of course if Crabb’s plan had been to leave his life in Britain behind and defect to the Soviet Union then he certainly executed a successful mission worthy of his fictional counterpart. Although, not very sporting of a British war hero it must be said!