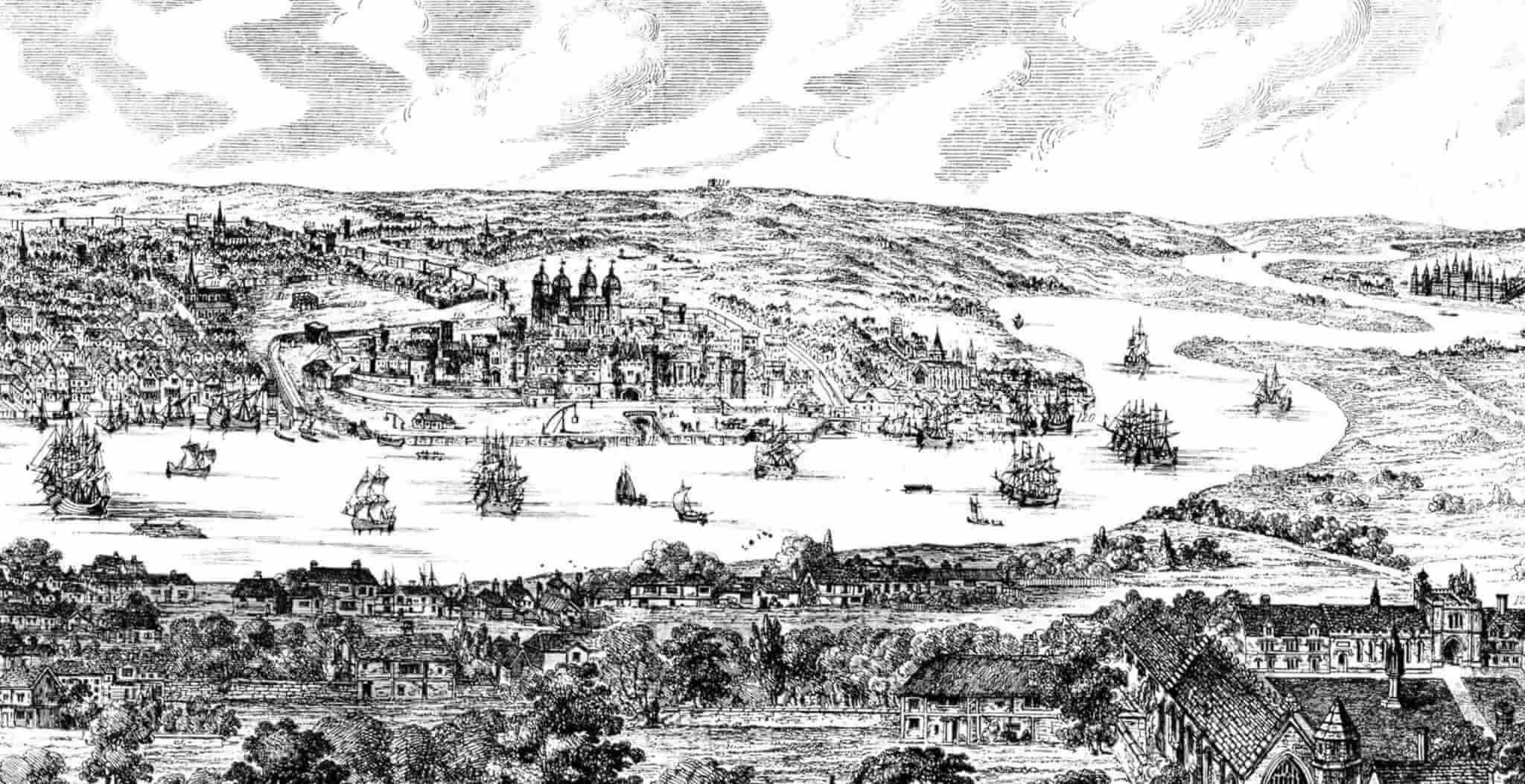

When crisis strikes, opportunity knocks, as the improvers of Restoration London knew all too well. In September of 1666, fire waged war on their city, and short-term panic soon gave way to thoughts of future gain. The Great Fire of London burned for five days, spreading with calamitous ease from its humble beginnings in Thomas Farriner’s bakery, Pudding Lane, to the farthest fringes of the walled City. When the flames eventually faltered, they left a charred ruin in their wake. The ashes burned hot underfoot for days and smoke was reported for weeks, even months. Yet, with the medieval fabric of the town razed, an unparalleled chance for urban renewal beckoned.

London before the Fire was filthy, insalubrious and ramshackle, characterised by a dense web of streets and alleys, organic in their growth and ancient on plan. Buildings jettied out from upper storeys and made caves of winding lanes. Walls were built from flammable plaster and lath; roofs often of thatch.

‘Before the Fire of London, Anno 1666’, Daniel Defoe wrote decades later, remembering the city of his youth, ‘the Buildings looked as if they had been formed to make one general Bonfire’.

Additionally, measures for public sanitation were all but absent, themselves hampered by the layout of the city. In the year before the Fire, London had suffered a dreadful visitation in the form of the Great Plague, which spread rapidly in such unsanitary conditions.

Contemporaries recognised these ailments, they simply lacked the opportunity to fix them.

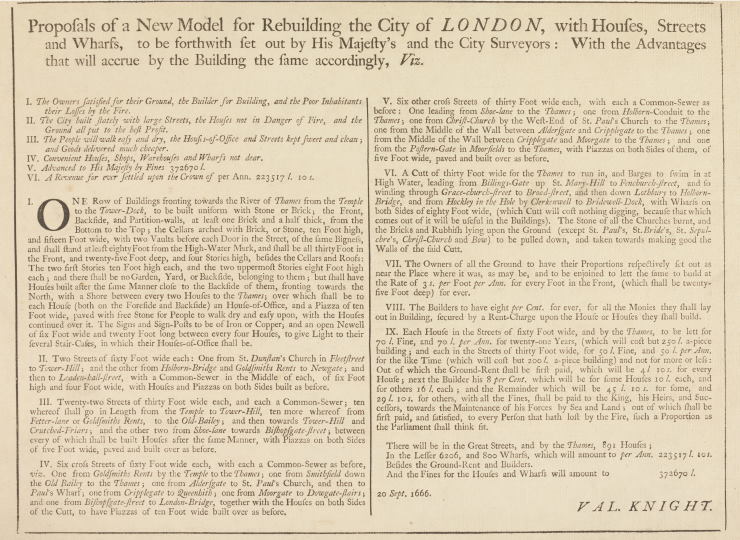

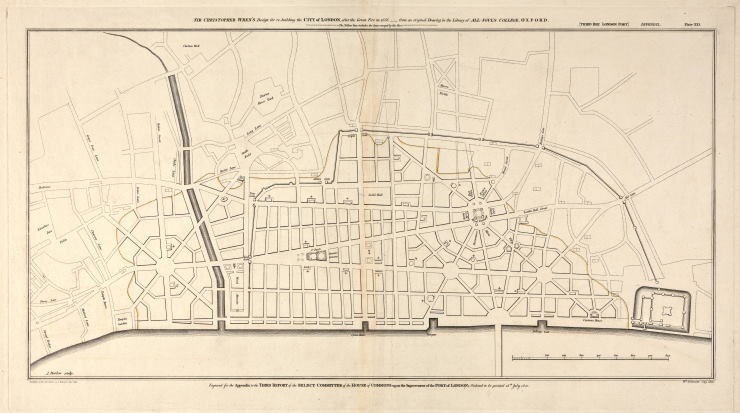

For some, the devastation of the City presaged its phoenix-like rebirth, and offered a chance to rectify London’s historic urban challenges. Among responses, the post-Fire proposals of Christopher Wren and John Evelyn have become widely known, as have those of Robert Hooke, Valentine Knight and several others. These envisaged a new London in the mould of a rationally-planned or Baroque European capital after the Paris of Henri IV or Sixtus V’s Rome. Grand avenues and rond-points, the canalisation of the Fleet River, and the construction of a quay alongside the Thames all featured among ideas. Although a number of the virtuosi who produced these plans had the ear of the king, Charles II, their visions failed to have any serious effect on post-Fire urban planning in London.

And yet, the City did rise again, and for contemporaries, it was felt to have done so in a more orderly and healthier manner. As part of this, appraisals of post-Fire London often braided political splendour and diffuse material improvement together. Naturally, puff played its part. However, by most accounts, a sincere awareness of the opportunities for urban improvement provided by the Fire was widespread.

The 1667 and 1670 Rebuilding Acts enshrined a series of procedures which acted on this sentiment. As a measure against the incidence of large fires, new buildings were to be built in brick or stone, with the use of flammable materials restricted. To halt the spread of flames, jettying upper storeys or protruding signs were banned and party walls mandated. Four distinct classes of building type were described in the legislation too, determined by their proximity to large thoroughfares and newly-widened streets, standardizing the dimensions as well as the materials of the rebuilt City.

In addition to laying the foundations for an urban architectural vernacular which, through the actions of developers like Nicholas Barbon, informed the design of the now ubiquitous London townhouse, these measures had a demonstrable effect on perceptions of cleanliness and metropolitan health. Indeed, for a number late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century observers, the rebuilding of London amounted to an experiment in early modern sanitation.

This was understood according to contemporary standards of public health and medicine. In an offshoot of miasmatic theories, for example, wider streets were felt to ease the passage and so dispel the effects of ‘bad air’ caused by filth, disease, and atmospheric pollution. ‘[S]ince the Enlargement of the Streets, and modern Way of Building’, one mid-eighteenth-century writer explained, ‘by the Re-edifying of London there is such a free Circulation of sweet Air thro’ the Streets, that offensive Vapours are expelled, and the City free from all pestilential Symptoms for these eighty-nine Years’.

As this quote suggests, the Fire was also thought to have cleansed London of plague, of which there were no more substantial outbreaks in England after 1665. Whether by purging the ‘seeds’ of the disease from the soil or purifying miasmatic air, the reasons given by contemporaries to this seemingly miraculous development were invariably misplaced. In addition to developing resistance to the vectors of plague among rodents, the more likely causes for its decrease, however, involved the sequestration of these same rats and their fleas from human populations by providing secure, salubrious dwellings. The epidemic and epizootic dimensions of its disappearance in London were therefore related to, if not grounded in, the material aspects of the post-Fire response.

While it would be wrong to overstate the impact of the post-Fire drive for urban improvement, it would be worse to discount its incidence. In the course of the next century, building legislation expanded on the effects of these early measures, with the 1709 and 1774 London Building Acts especially contributing to a widespread standardisation of design and building methods pioneered in 1667.

This influenced practices throughout Britain, as well as establishing a new metropolitan urban aesthetic. Central to this story of urban renewal were those measures impacting public health. A reborn London was a healthier London – at least in theory. The story of the City’s improvement would unfold across the next two and a half centuries, right down to the present day. If the big smoke is any cleaner today than it was the day before, we owe it at least in part to a few licks of flame from a baker’s oven.

Jake Bransgrove is an independent scholar specialising in British cultural history, with a focus on the architecture of London. He holds degrees from the University of Auckland, New Zealand and The Courtauld Institute of Art.