The turmoil which followed the Reformation created an array of martyrs on both sides of the religious divide. One such martyr, nicknamed ‘the pearl of York’, was Margaret Clitherow, a staunch Catholic who lost her life in the name of Catholicism.

Born in 1556 in York, Margaret Middleton was the daughter of the sheriff of York and church warden of St Martin’s church in Coney Street. As a child, Margaret would have observed to state religion, Protestantism, and this religious affiliation seems to have continued until the early 1570s at which point it seems that she was converted to Catholicism by the wife of Dr Thomas Vavasour, a prominent Catholic in York.

By this point, Margaret had married John Clitherow, a prosperous butcher who owned a shop on the Shambles. However, keeping the people of York supplied with fresh meat was not the sole job of John who was also responsible for reporting Catholic worshippers to the authorities who were, in line with the Elizabethan Settlement, Protestant. This would have almost certainly created tension in their marriage as Margaret began to subvert the authorities and the official church, a matter complicated by her decision to be a recusant (a non-church attender) in the years following her conversion.

Though Margaret had now escaped death multiple times, her ultimate downfall would come from her desire to emulate a model established by the ‘upper sort’. It was not uncommon at this time for noble families to harbour priests secretly in their houses, hiding them in priest holes or concealing their identities by claiming that they were schoolmasters or music teachers for their children.

Indeed, this frequently proved to be effective as noble families had the space, finances and means to support and conceal priests, often living in isolated houses which rarely seemed suspicious to locals. However, this model could not be effectively applied to a ‘middling sort’ household on the bustling Shambles in York.

Margaret had succeeded in creating a concealed room in her home on the Shambles along with a secret cupboard in which she hid the priest’s vestments and wine and bread for the mass, but failed to keep it secret, resulting in a frightened young boy revealing its location to the authorities when they raided her home in March 1586. Margaret was subsequently arrested for harbouring priests, something which had been made a criminal offence punishable by death in an Act of Parliament of 1581.

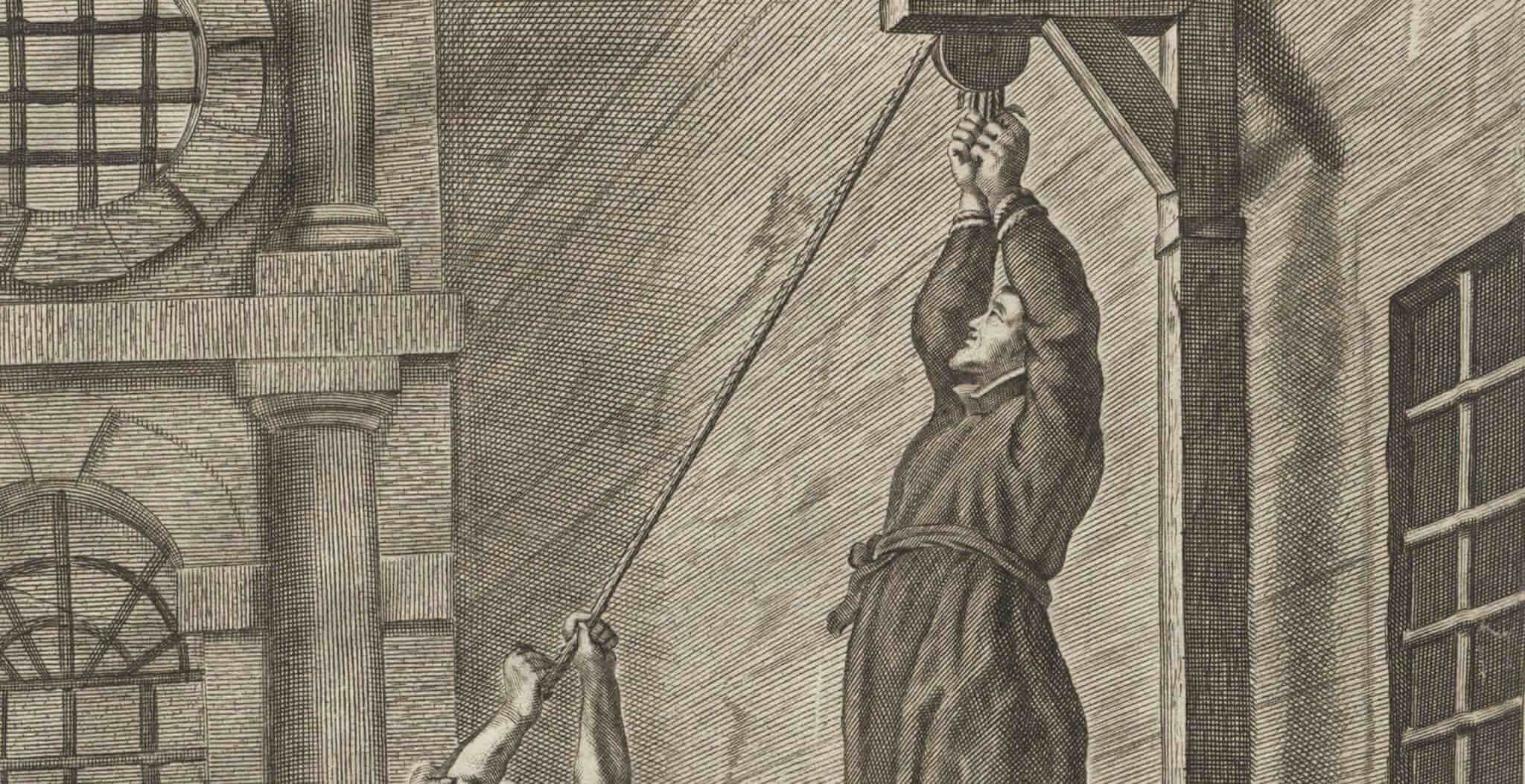

Perhaps she was genuinely fervent, unwilling to sacrifice the religion she saw as ‘true’ or perhaps she was determined to become a martyr like those she had so obviously revered. Some have even claimed that her refusal stemmed from her unwillingness to include others in the trial, as her friends and family would need to be questioned alongside her. Whatever the cause of her insistence, she was taken to the toll-booth on Ouse Bridge on 25th March 1586 and was pressed under seven or eight hundredweight (approximately eight hundred to nine hundred pounds) until she died roughly fifteen minutes later. Margaret left behind her husband and three children, whom Margaret had educated in the Catholic faith. Her son, Henry Clitherow, went abroad to train as a priest before returning to England as a missionary.

Opinions on Margaret Clitherow have varied throughout history. Many of her contemporaries deemed her to be mad whilst Henry May, Lord Mayor of York and Margaret’s stepfather claimed that Margaret had committed suicide. Whilst this may show that he believed Margaret to have been rather stupid in her decision, it also shows an attempt on May’s behalf to preserve his position. In condemning his stepdaughter’s behaviour, May showed his personal convictions distinctly differed from Margaret’s, helping to bolster rather than diminish his position. Somewhat unusually, Elizabeth I herself seemed to condemn the killing of Margaret, writing a letter to the people of York which stated that Margaret should have been spared the terrible fate on account of her gender alone. In more recent history, Margaret has been revered rather than condemned, being canonised by Pope Paul VI in October 1970 as one of forty English martyrs. It was also Pope Paul VI who first called Margaret ‘the pearl of York’.

By Zoe Screti. I am a student of history at the University of Birmingham. Having just completed my undergraduate degree, I am progressing on to a master’s degree in Early Modern history. I am a self-confessed history nerd with a particular fascination with all things Tudor.