“And, the truth is, I do fear so much that the whole kingdom is undone”

These were the words of Samuel Pepys, taken from his diary entry on 12th June 1667, a stark reminder of the victorious Dutch attack launched on the unsuspecting Royal Navy. This attack became known as the Raid on Medway, a humiliating loss for England and one of the worst in the history of the navy.

The defeat was a terrible blow to England. The raid itself formed part of a much larger conflict known as the Anglo-Dutch Wars.

Beginning in 1652, the first Anglo-Dutch War concluded with the Treaty of Westminster, an agreement between Oliver Cromwell and the State General of the United Netherlands to end the fighting. Whilst the treaty had the desired effect of subduing any immediate threats, the commercial rivalry between the Dutch and British was only just beginning.

The restoration of King Charles II in 1660 resulted in a surge of optimism and nationalism amongst the English, and coincided with a concerted effort to reverse the domination of Dutch trade. As Samuel Pepys himself noted in his famous diary, the appetite for war was on the increase.

The English remained focused on mercantile competition, hoping to seize Dutch trade routes. By 1665 James II, Charles’s brother managed to seize the Dutch colony in what is now known as New York.

Meanwhile, the Dutch, keen not to repeat the losses of the previous war were busy preparing new, heavier ships. The Dutch also found themselves in a better position to afford to engage in war whilst the English fleet had already been suffering from cash flow problems.

In 1665, the Second Anglo-Dutch War broke out and was set to last another two years. Initially, at the Battle of Lowestoft on 13th June, the English won a decisive victory, however over the coming months and years England would suffer a series of setbacks and challenges which would weaken its position greatly.

The first disaster involved the ravaging effects of the Great Plague which had a horrific impact on the country. Even Charles II was forced to flee from London, with Pepys observing “how empty the streets and how melancholy”.

The following year, the Great Fire of London added to the dismal morale of the country, leaving thousands homeless and dispossessed. As the situation became more dire, suspicions arose about the cause of the fire and quickly the mass panic turned into rebellion. The people of London directed their frustration and anger at the people whom they feared the most, the French and Dutch. The result was mob violence on the streets, looting and lynching as the atmosphere of social discontent reached boiling point.

In this context of hardship, poverty, homelessness and fear of the outsider, the Raid on Medway was the final straw. A stunning victory for the Dutch who had calculated the best time to act against England, when her defences were low and economic and social upheaval was aplenty.

The circumstances were dire with English sailors consistently unpaid and receiving IOUs from the Treasury which had a serious cash crisis. This proved to be a meaningless gesture for men who were struggling to support their families. For the Dutch, this was the perfect context in which to launch an attack.

The mastermind was the Dutch politician, Johan de Witt, whilst the attack itself was carried out by Michiel de Ruyter. The assault was motivated in part as an act of revenge for the devastation caused by the Holmes’s Bonfire of August 1666. This was a battle which resulted in the English fleets destroying Dutch merchant ships and burning down the town of West Terschelling. Revenge was on the minds of the Dutch and the English were in a vulnerable position.

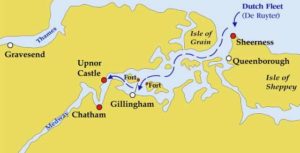

The first sign of trouble appeared when the Dutch fleet was spotted on 6th June in the area of the Thames Estuary. Days later they would already be making alarming progress.

One of the first errors on the side of the English was not addressing the threat as soon as possible. The underestimation of the Dutch immediately worked in their favour as the alarm was not raised until 9th June when a fleet of thirty Dutch ships emerged just off Sheerness. At this point, the desperate Commissioner at the time Peter Pett contacted the Admiralty for help.

By 10th June, the seriousness of the situation was only just beginning to dawn on King Charles II who sent the Duke of Albemarle, George Monck to Chatham to take control of the situation. Upon arrival, Monck was dismayed to find the dockyard in disarray, with not enough manpower or ammunition to ward off the Dutch. There was a fraction of the men needed to support and defend, whilst the iron chain used to defend against incoming enemy ships had not even been put in place.

Monck went about putting hasty defence plans into place, ordering cavalry to defend Upnor Castle, installing the chain into its correct position and using blockships as a barrier against the Dutch in case the chain based at Gillingham was broken. The realisation came all too late as the fleet had already arrived at the Isle of Sheppey which was only defended by the frigate Unity which had failed to ward off the Dutch fleet.

Two days later, the Dutch reached the chain and the attack was launched by Captain Jan Van Brakel which resulted in Unity being attacked and the chain broken. The events that followed were catastrophic for the English navy, as the guardship Mathhias was burnt, as was the Charles V, whilst the crew had been seized by Van Brakel. Seeing the chaos and destruction Monck took the decision to sink the sixteen remaining ships rather than have them captured by the Dutch.

The following day on 13th June, there was mass hysteria as the Dutch continued to advance into Chatham docks despite being under fire from the English stationed at Upnor Castle. Three of the English Navy’s largest ships, the Loyal London, Royal James and the Royal Oak were all destroyed, either deliberately sunk to avoid capture or burnt. These three ships in the aftermath of the war were eventually rebuilt, but at a great cost.

Finally on 14th June Cornelius de Witt, Johan’s brother, decided to withdraw and retreated from the Docks with his prize, the Royal Charles as a trophy of the war. Following their victory the Dutch attempted to attack several other English ports but to no avail. Nevertheless, the Dutch returned to the Netherlands triumphant and with proof of their victory against their commercial and naval rival, the English.

The humiliation of the defeat was felt keenly by King Charles II who saw the battle as a threat to the Crown’s reputation and his personal prestige. His reaction was soon to be one of the factors in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, as resentment continued to fester between the two nations.

The battle to dominate the seas continued.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.