Turn again, Whittington,

Once Lord Mayor of London!

Turn again, Whittington,

Twice Lord Mayor of London!

Turn again, Whittington,

Thrice Lord Mayor of London!

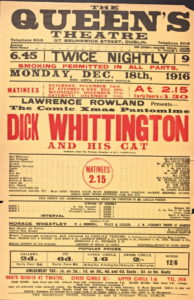

When that time of year approaches and pantomime season is in full swing, Dick Whittington and his cat have become a permanent fixture on the stage year after year. In fact, their popularity stems from the traditional tale which was performed in the theatres of the 19th century, dating back to 1814.

The performance follows the story of a poor boy from Gloucestershire who sets out for London, determined to make his fortune. Met with disappointment, Dick is resolved to return home until he hears the Bow Bells ringing out and he realises it must be a message of good fortune coming his way. The following events unfold with adventures accompanied by a cat resulting in his ultimate prosperity and becoming Mayor of London.

With such a folkloric tale, it is unsurprising that its popularity grew and grew, branching out into different adaptations ranging from pantomime, opera and as a puppet play performed at Covent Garden. In fact, such an early interpretation was recorded by the famous diarist Samuel Pepys in his entry on 21st September 1668; he commented:

“To Southwark Fair, very dirty, and there saw the puppet show of Whittington, which was pretty to see”.

In the 1700s, the renowned puppeteer Martin Powell was performing “Whittington and his Cat” with much success.

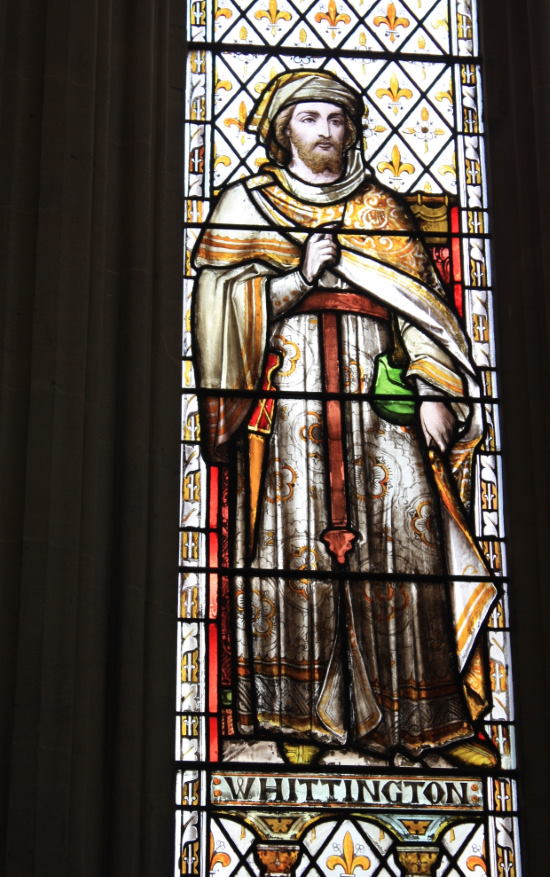

The story of Whittington and his famous cat companion had captured the imagination of pre-Victorian society. Today, this tale continues to entertain. There is a statue of Whittington and his cat on Highgate Hill, the place where Dick supposedly stood and heard the calling of the Bow Bells, compelling him to return.

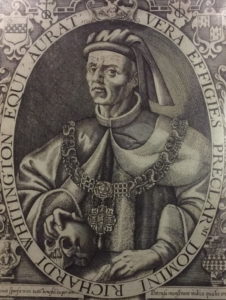

With such celebrated status, what can be said of the real life inspiration behind such a story? Well, perhaps this is the most surprising part. Richard Whittington, the protagonist of such elaborate fables was in fact Lord Mayor of London, as well as an accomplished wealthy merchant. However, his background could not have been more different from the fictitious rags to riches story many are more familiar with.

Whilst the fictional account of his life describes his epic journey from a poor family to the riches that the city of London had to offer, in fact, the real Whittington was not from a lower class background. Furthermore, his feline companion has yet to be corroborated by any evidence.

The folklore of a boy and his cat was widespread throughout Europe, thought to have perhaps originated in medieval Persia. However the legend based on Whittington appears to have taken on a life of its own.

Richard Wittington’s actual story begins in the 1350s, born into a wealthy titled family in Gloucestershire. His father was Sir William Whittington who served as a Member of Parliament, and his mother was Joan Maunsell who was the daughter of an MP. Richard was therefore no stranger to the demands of political life, in fact it seemed to run in his family. Two of his brothers, Robert and William both served as MPs.

Richard soon found himself in an equally prominent position, whilst also making noteworthy contributions in the form of a variety of public projects, endorsements and investments in infrastructure.

As he was not the eldest son, Richard knew he would not inherit his father’s estate and thus he made his way to London, seeking to make his own fortune. In order to do this he went to the City of London and began learning the ropes as a mercer, a trader of fabrics, which was a burgeoning business at the time.

Before long, his chosen profession was beginning to pay dividends and he quickly grew to become a very successful merchant specialising in luxury fabrics and benefiting from some extremely important clientele, including members of the royal family and the higher echelons of society.

It is believed that in two years alone, he sold garments to King Richard II worth around £1.5 million in today’s money. His successful career as a trader thus allowed him to become a money-lender and by 1397 he had lent considerable amounts of money to the king.

Now as a wealthy man in his own right, a businessman in favour with the king, Whittington moved in diplomatic and highly influential circles. His close relationship with royalty continued, even when Richard II was deposed.

Whittington had already established a professional relationship with the soon-to-be King Henry IV and by the time he became king Whittington found himself in a similar relationship to the one he enjoyed with his predecessor.

Over the years, Whittington’s kudos as a member of the inner circle close to royalty held him in good stead in a variety of more professional positions. By the 1380s he was serving as a Councilman for London and by 1393 he was an Alderman and Sheriff of the City of London.

In June 1397 he succeeded Adam Bamme as Lord Mayor of London after Bamme passed away before his second term was finished. King Richard II subsequently recommended Whittington for this position and so it was decided. A few months later he was formally elected on 13th October, after Whittington had displayed his credentials when he restored the city’s liberties from the king.

Whittington used his new sway in monarchical circles in order to gain further political influence. His loans allowed him input over policy matters and civic issues of which he was heavily involved.

Perhaps most remarkably he was able to maintain consistent relationships with subsequent heirs to the throne despite infighting and disagreements between successors.

Whittington held the position of Mayor four times. His re-appointment showed how he had also won over the public.

In 1416 he, like his brothers, became a Member of Parliament, yet another professional role to add to his long list of accomplishments.

Whilst Richard II had helped him to acquire the role of mayor, Whittington would maintain his influence with subsequent kings, including Henry V to whom he lent money. In return he was offered a job as a manager of the expenditure used for the completion of Westminster Abbey.

Whittington’s influence with trade, expenditure and public projects led to his involvement in many royal commissions. His opinion was sought, trusted and put into practice on a number of occasions.

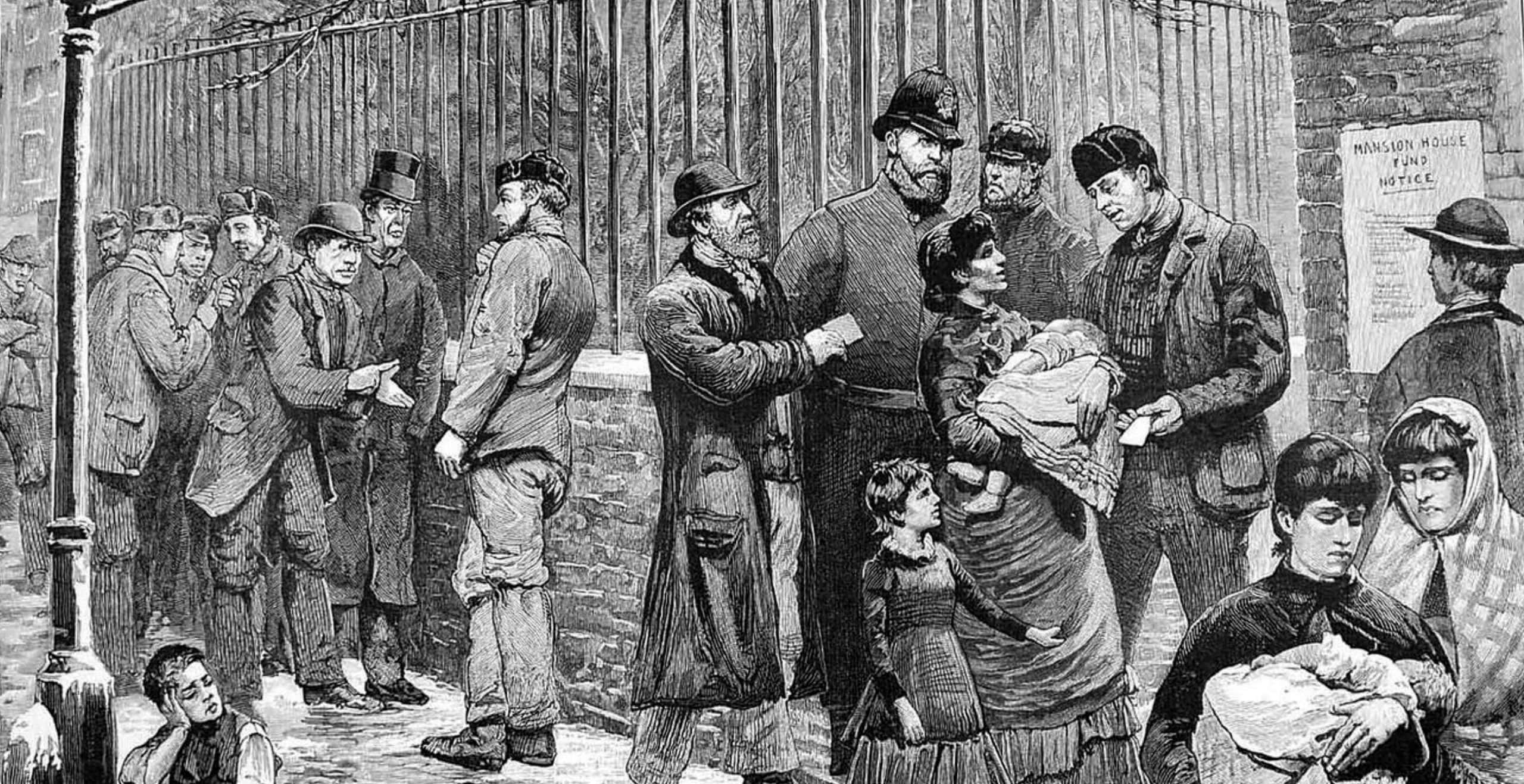

During his service, he helped to complete and finance a number of valuable infrastructure projects, including introducing drainage to improve the living conditions of some of London’s poorest neighbourhoods.

Whilst he married late in his life to a very important woman called Alice Fitzwaryn, who was an heiress with her sister to her father’s fortune; sadly they did not produce an heir and so Whittington’s wealth is best seen in his investment of his chosen home, London.

Across the course of his lifetime and later when he died, he left in his will, a considerable legacy dedicated to his adopted hometown. Some of the biggest recipients of his investment included the ward for unmarried mothers at St Thomas’ Hospital, as well as producing a drainage system in Billingsgate and public toilets to improve the health and living conditions of many.

His strong sense of duty to his city extended to his decision to prevent animal skins being washed in the Thames, as many young boys had lost their lives from hypothermia when completing such a task.

His endowments included rebuilding his parish church as well as the Guildhall.

Richard Whittington passed away in 1423 but his legacy lived on both in London and on the stage. Whilst many now have forgotten the man behind the myth, his legend continues to play out in theatres around the country.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: July 5th, 2021