Magna Carta, one of the documents upon which our democratic system is based, and a forerunner of the U.S. Constitution, dates back to 1215. Soon after it came into force, some English landowners known as barons declared that King John was not abiding by Magna Carta and they appealed to the French Dauphin, later to be King Louis VIII, for military assistance against King John. Louis sent knights to aid the rebel barons, and England was then in a state of civil war which lasted until September 1217.

I grew up in Lincoln and went to Westgate School, which is situated just north of the castle walls, very close to where the decisive Battle of Lincoln took place on 20th May 1217. However, it is only in recent times that I have learned of the famous battle, which was decisive in preventing England from falling under French rule. Why it is kept so quiet I do not know! It is in some ways at least as significant as the Battle of Hastings, which, when all is said and done, was a defeat!

In May 1216 and against the wishes of Pope Innocent III, Louis sent a full-scale army, which landed on the coast of Kent. The French forces, together with the rebel barons, soon had control of half of England. In October 1216, King John died of dysentery at Newark Castle and the nine-year-old Henry III was crowned in Gloucester. William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, acted as the King’s Regent and he succeeded in drawing the majority of England’s barons to support Henry.

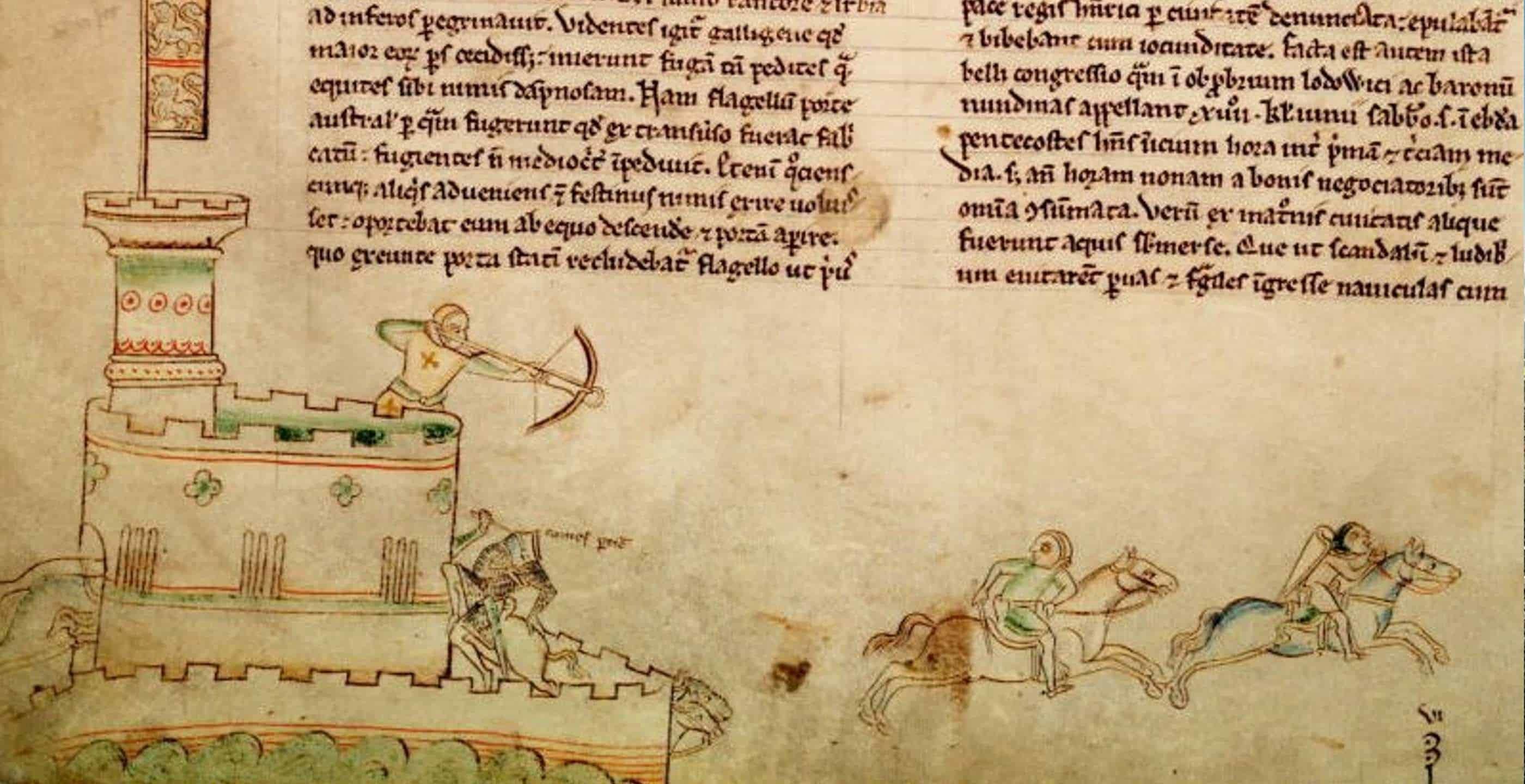

In May 1217 Marshal was in Newark, the King being in nearby Nottingham at the time, and he appealed to loyal barons for their help in attempting to relieve the siege, by rebels and French troops, of Lincoln Castle. The Castle was under the control of a remarkable lady, Nichola de la Haye, whom King John, on a visit in 1216, had appointed Sheriff of Lincolnshire. This was most unusual in those far-off days. Louis promised Nichola safe passage if she would surrender to him. She said “No!” Most of Lincoln’s citizens did, however, support the French claimant to the English throne.

Marshal, with 406 knights, 317 crossbowmen and other fighting men, marched from Newark to Torksey on the plain north-west of Lincoln, eight miles distant, and sent some men nearer to the city. He was wise not to approach from the south. It would probably have been impossible to scale the tall hill upon which Lincoln is built, but, as it was, his forces reached Lincoln and broke through the West Gate of the city.

The Earl of Chester did the same at Newport Arch (a Roman structure which survives to the present day). The French forces were taken by surprise at being attacked by such large numbers of men, and savage fighting ensued in the narrow streets close to the cathedral and castle. The French commander, Thomas Count du Perche, was killed. He is said to have had 600 knights and over 1,000 infantrymen under his command. The rebel leaders Saer de Quincey and Robert Fitzwalter were taken prisoner and many of their men surrendered. Others fled downhill, and the forces loyal to Henry III then exacted heavy retribution upon Lincoln and its citizens, causing much destruction, even to churches. Women and children who tried to flee from the soldiers drowned when their overloaded boats capsized on the River Witham.

Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, said to his men before the battle: “If we beat them, we will have won eternal glory for the rest of our lives and for our kin.” The Second Battle of Lincoln did indeed turn the tide of the war, known as The First Barons’ War, and it prevented England from becoming a French colony.

By Andrew Wilson. Andrew Wilson grew up in Lincoln and went to Durham University. For over twenty years he worked for an aid agency based in south west London. His interests are many, and include making acrylic paintings.

Published: 4th February 2019.