The South Sea Bubble has been called: the world’s first financial crash, the world’s first Ponzi scheme, speculation mania and a disastrous example of what can happen when people fall prey to ‘group think’. That it was a catastrophic financial crash is in no doubt and that some of the greatest thinkers at the time succumbed to it, including Isaac Newton himself, is also irrefutable. Estimates vary but Newton reportedly lost as much as £40 million of today’s money in the scheme. But what actually happened?

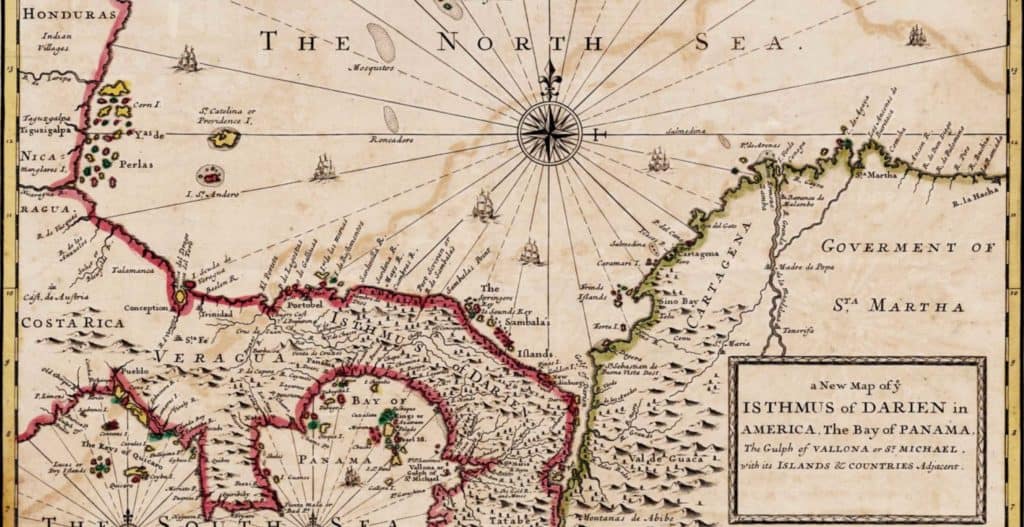

It all began when a British joint stock company called ‘The South Sea Company’ was founded in 1711 by an Act of Parliament. It was a public and private partnership that was designed as a way of consolidating, controlling and reducing the national debt and to help Britain increase its trade and profits in the Americas. To enable it to do this, in 1713 it was granted a trading monopoly in the region. Part of this was the asiento, which allowed for the trading of African slaves to the Spanish and Portuguese Empires. The slave trade had proved immensely profitable in the previous two centuries and there was huge public confidence in the scheme, as many expected slave profits to increase dramatically, especially when the War of the Spanish Succession came to an end and trade could begin in earnest. It didn’t quite play out like that however…

The South Sea Company began by offering those who bought stocks an incredible 6% interest. However, when the War of the Spanish Succession came to an end in 1713 with the Treaty of Utrecht, the expected trade explosion did not happen. Instead, Spain only allowed Britain a limited amount of trade and even took a percentage of the profits. Spain also taxed the importation of slaves and put strict limits on the numbers of ships Britain could send for ‘general trade’, which ended up being a single ship per year. This was unlikely to generate anywhere close to the profit that the South Sea Company needed to sustain it.

However, King George himself then took governorship of the company in 1718. This further inflated the stock as nothing instils confidence quite like the endorsement of the ruling monarch. Incredibly, soon afterwards stocks were returning one hundred percent interest. This is where the bubble began to wobble, as the company itself was not actually making anywhere near the profits it had promised. Instead, it was just trading in increasing amounts of its own stock. Those involved in the company began encouraging – and in some cases bribing – their friends to purchase stock to further inflate the price and keep demand high.

Then, in 1720, parliament allowed the South Sea Company to take over the national Debt. The company purchased the £32 million national debt at the cost of £7.5 million. The purchase also came with assurances that interest on the debt would be kept low. The idea was the company would use the money generated by the ever-increasing stock sales to pay the interest on the debt. Or better yet, swap the stocks for the debt interest directly. Stocks sold well and in turn generated higher and higher interest, pushing up the price and demand for stocks. By August 1720 the stock price hit an eye-watering £1000. It was a self-perpetuating cycle, but as such, lacked any meaningful fundamentals. The trade had never materialised, and in turn the company was just trading itself against the debt that it had bought.

Then in September of 1720, some would say an inevitable disaster struck. The bubble burst. Stocks plummeted, down to a paltry £124 by December, losing 80% of their value at their height. Investors were ruined, people lost thousands, there was a marked increase in suicides and there was widespread anger and discontent in the streets of London with the public demanding an explanation. However, even Newton himself couldn’t explain the ‘mania’ or ‘hysteria’ that had overcome the populous. Perhaps he should have remembered his apple. The House of Commons, wisely, called for an investigation and when the sheer scale of the corruption and bribery was unearthed, it became a parliamentary and financial scandal. Not everyone had succumbed to the ‘group think’ or ‘speculation mania’ however. A vociferous pamphleteer by the name of Archibald Hutcheson had been extremely critical of the scheme from the beginning. He had placed the actual value of the stock at around £200, which subsequently turned out to be about right.

The person that came to the fore to sort out the issue was none other than Robert Walpole. He was made Chancellor of the Exchequer and there is no doubt that his handling of the crisis contributed to his rise to power. In an effort to prevent an event such as this from happening again, the Bubble Act was passed by parliament in 1720. This forbade the creation of joint-stock companies such as the South Sea Company without the specific permission of a royal charter. Somewhat incredibly, the company itself persisted in trading until 1853, albeit after a restructuring. During the ‘bubble’ around 200 ‘bubble’ companies had been created, and whilst many of them were scams, not all were nefarious. The Royal Exchange and London Assurance survive to this very day.

Today, there are many commentators drawing comparisons between ‘Cryptocurrency mania’ and the South Sea Bubble, and note that, ‘promoters of the Bubble made impossible promises.’ Perhaps historians of the future will have cause to look back with similar incredulity on today’s market. Only time will tell.

“Bubbles, bright as ever Hope

Drew from fancy – or from soap;

Bright as e’er the South Sea sent

From its frothy element!

…

See!—But hark my time is out —

Now, like some great water-spout,

Scaterr’d by the cannon’s thunder,

Burst, ye bubbles, burst asunder!”

— Thomas Moore